DOI: https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2025.85.01.3

Volume 14 - Issue 85: 35-44 / January, 2025

How to Cite:

Danilina, S. (2025). Idioms in academic writing: A Ukrainian university case. Amazonia Investiga, 14(85), 35-44. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2025.85.01.3

Idioms in academic writing: A Ukrainian university case

Використання ідіом в академічному письмі: на прикладі текстів українських студентів

Received: December 10, 2024 Accepted: January 25, 2025

Written by:

Svetlana Danilina

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2005-9363

Ph.D. in Translation Studies, Associate Professor, Department of Foreign Languages for the Faculties of History and Philosophy, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine. WoS Researcher ID: AAC-6530-2020 - Email: sv.danilina@gmail.com

Abstract

This study investigates the use of idiomatic expressions in academic writing by Ukrainian university students learning English as a foreign language. The research analyzes the frequency of idiom use in essays written by two groups of students: one group explicitly taught academic English idioms and a control group. Findings reveal that Ukrainian students employ idiomatic expressions more frequently than native English speakers, as evidenced by comparisons with the British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus and the Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (MICASE). Notably, even the control group exhibited higher idiomaticity than their native-speaker counterparts. These results highlight the importance of addressing idiomatic language in academic English instruction for non-native speakers. The study discusses the potential benefits and challenges of incorporating idioms into teaching materials and provides insights for educators aiming to improve the phraseological competence of their students.

Keywords: Idioms, metaphorical language, academic writing, corpus data, formulaic competence.

Анотація

У статті досліджуються особливості використання ідіоматичних виразів в академічному письмі на основі текстів, написаних англійською студентами філософського факультету українського внз. У дослідженні було проаналізовано тексти двох груп українських студентів: Група 1, яка вивчала ідіоми на занятті з загальної та академічної англійської, та Група 2 (контрольна). Виявилося, що частотність застосування ідіом українськими студентами була вищою, ніж зафіксована в британському корпусі усної академічної англійської та у корпусі академічних текстів Мічиганського університету. Цікаво, що частотність використання ідіом навіть у контрольній групі виявилася вищою, ніж у студентів англомовних університетів. Результати дослідження свідчать про важливість вивчення ідіоматичної мови у курсі англійської для академічних цілей. У розвідці також обговорюються переваги і складнощі включення вправ з ідіоматичних виразів до навчальних матеріалів і пропонуються можливі шляхи підвищення фразеологічної компетентності студентів.

Ключові слова: Ідіоми, метафорична мова, академічне письмо, корпусні дані, ідіоматична компетентність.

Introdution

University students’ competence at academic writing (AW) has been recognized as an important constituent of their successful professional career, which requires not just the ability to generate a scientific idea, but also to convey it to the scientific community by adhering to the principles and conventions accepted in academic discourse. Although the domain of AW leans towards straightforward formulations that sound factual, accurate and explicit, it does not mean that any use of figurative language is out of place in this field. On the contrary, relevant idioms or metaphors can contribute to formulating one’s scientific concept in a more vivid way, making it easier for the reader to grasp, or to enriching the author’s lexical repertoire and giving a break to the audience from a plain, purely scientific style.

Figurative language, which comprises idiomatic expressions, is universally considered to be a hard nut to crack for foreign language learners. Ta’amneh (2021) states that learning English is a difficult task overall due to the lack of students’ exposure to the target language in daily life, while mastering idioms is possibly hardest of all. A lot of scholars agree that the challenges in acquiring figurative language are caused primarily by the fact that the overall meaning of idiomatic expressions is normally quite different from the meanings of their constituent words, which is at times complemented by their deceptive transparency (Szudarski, 2017; Park & Chon, 2019). Other researchers emphasise cultural differences and the lack of direct idiomatic equivalence – incongruency – between the learners’ L1 and L2, which contribute to the confusion (Stamenkoska, 2017; Peters, 2016; Snoder, 2017; Lysanets & Bieliaieva, 2023; Rahmtallah, 2024).

Thus, on the one hand, learning a foreign language is rendered more difficult because of having to master its idiomatic aspect, while on the other hand, a solid command of idiomatic formulae enhances both the quality of expressing oneself in L2, as well as comprehending the message uttered in L2 (Szudarski, 2017; Simpson & Mendis, 2003). Given the complexity of acquiring formulaic language, it would be logical to assume that the number of idiomatic collocations used in the academic writing by Ukrainian students would be lower than that of students of an American university.

My research therefore seeks to investigate this assumption and to find out if idioms are indeed employed by Ukrainian university students in their academic texts, written in English. Other aims of my paper are to analyse if the fact of explicitly discussing the use of idiomatic language in academic domain has affected the actual number of idiomatic expressions in the learners’ written output, and to compare the possible instances of idiom occurrence in the texts by Ukrainian students with that in the academic writing of their American counterparts, both the overall frequency and the rate of individual idiom use.

The article includes the following sections:

Literature Review

It has been suggested by linguistic research that natural language is permeated with metaphor, whose “locus is not in language but in the way we conceptualize one mental domain in terms of another” (Lakoff, 1993, p. 202), thus making it an inherent feature of human thinking. Idioms, which could be defined as a subcategory of metaphorical language (Lazar, 2003), are viewed as part and parcel of popular culture, fiction, and everyday speech, however, their usage is not restricted to the above linguistic areas, with idiomaticity having been recognized to be a common feature of academic speech and writing (Miller, 2020; Vongpumivitch, Yu, & Nguyen, 2023; Simpson & Mendis, 2003; Biber & Barbieri, 2007; Ädel & Erman, 2012; Shin, 2019). According to Miller (2020), deliberate avoidance of idiomatic language in one's AW may be a sign of a lack of phraseological competency, which can mark a writer out as uninformed of the conventions of a discourse community.

A special role of metaphorical language in academic discourse is analysed in the research by J.B. Herrmann (2013), who points out a higher percentage of “metaphor-related words” in academic realm compared to other contexts, such as news, fiction or conversation. In the academic context, metaphors can reveal the ways of conceptualisation of abstract notions and ideas, typical for a specific culture, as well as contribute to the distinct sounding of an authorial voice in a scientific text, and thus be viewed as a means of formulating evaluation. Other functions of figurative language singled out by scholars include reference of an entity, creating textual cohesion, providing illustrative explanation, paraphrasing, creating a sense of group identity, or signposting a change of topic (Herrmann, 2013; Ruskan et al., 2023; Simpson & Mendis, 2003). The numerous roles played by metaphorical expressions in constructing a text add to the list of reasons why teachers need to address idiomaticity, regardless of their target English Language Teaching specialism, be it English for Specific or Academic Purposes, or General English courses.

H.Q. Tran (2017) states that idiom learning and teaching has indeed gained a lot of popularity in English learning context, therefore the assessment of how well the learners actually use idioms is a growing trend. This observation is supported by Oakey (2020) according to whom, the central role of phraseology in language in general and in academic context in particular has been revealed in the recent years by an increasing adoption of corpus techniques by language scholars. Although the realization of the fact that academic discourse is the right place for figurative language seems to be gaining ground, the corpora-based research into the actual quantity of idioms per se used in academic domain – both spoken and written – remains fairly scarce. Among the studies relevant for the present research one could cite the work by Simpson and Mendis (2003), who discussed the corpus-based approach to researching and teaching idioms by drawing on the texts contained in the Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (MICASE), and Miller (2020), who aims to discover whether idioms indeed occur in academic discourse and seeks to identify the most frequently used items in the spoken and written texts of the British corpus of academic English (BASE).

One of the reasons for the lack of fundamental research that would delve into the amount of idiom usage in an academic context may be the general confusion over the terminology in the domain of formulaic language. In J. Miller’s words, “One person's ‘idiom’ may be another person's ‘phraseological unit’” (Miller, 2020). Idioms are indeed subject to various definitions and classifications: they could be included as a subcategory into broader fields of multiword units (Miller, 2020), recurring word sequences or lexical bundles (Shin, 2019); according to Per Snoder (2017), idioms are distinguished from phrasal verbs and collocations but all the three make up formulaic sequences; in her definition Mona Baker (2017) stresses the degree of fixedness in idioms and defines such collocations as “frozen patterns of the language that allow little or no variation in form” (p.67); on the other hand, Gillian Lazar (2003) does not distinguish between idioms and metaphors and maintains that these forms constitute “figurative or metaphorical language” (p. 1). Similarly, Rosamund Moon (1998) equals metaphors and idioms but argues against the notion of fixedness, observing that most idioms are in fact subject to variation, provided some trace of their canonical form is detectable. In the light of the above, several studies that did analyse the “idiomaticity” of the university students’ academic writing are not directly comparable with the present research, as in fact they covered a wider field of “multiword units”, which include recurring lexical sequences other than just idioms (e.g. Ädel & Erman, 2012; or Shin, 2019).

Although for the purposes of identifying idioms in the students’ writing, my research goes by the definition of the idiom proposed by Miller (2020): “an idiom is a multiword expression (more than one word in length), which is reasonably fixed syntactically, figurative, and, to a greater or lesser extent, opaque”, the overall approach of the article adheres to the vision of idioms as formulated by Lazar (2003), who views idiomatic expressions as part of a wider notion of metaphorical language.

Another issue that underlies a corpora-based study of academic discourse is the variety of types of academic texts produced by different categories of authors, which contributes to the difficulty of classification in this field (e.g. native vs nonnative speakers, novice vs expert writers, university writing vs published articles, etc.). As Y.K. Shin (2019) emphasizes, a lot of recent studies that examined the use of formulaic language in the academic context did not distinguish between, for example, university assignments and published texts. Therefore, the findings of such research “may blur the differences due to the characteristics of the groups and the confounding influences of register differences” (Shin, 2019, p.1). Accounting for this aspect, the comparative analysis presented in this paper focuses exclusively on university writing (not including published texts) and highlights the differences in the frequency of idiom usage considering the native speaker/ non-native speaker characteristic of the learners.

To sum up, the use of figurative language is currently viewed as an inherent feature of academic discourse, a tool which can perform various functions in the construction of academic texts. Although metaphorical expressions have been discussed in numerous studies, the investigations that would address the actual numbers of idiomatic multiword units employed in AW – and which would be particulalrly relevant for my research – have remained quite scarce, a probable reason for that being the overall confusion over the definitions and classifications that the domain of figurative language has traditionally been subject to. The idiomaticity of the AW done in English by Ukrainian students has also remained largely understudied, in terms of both qualitative and quantitave research. The lack of such investigations opens up a range of exploration perspectives in this area, which could eventually lead to enhancing the quality of teaching EAP to Ukrainian students.

Methodology

Participants: The written work, analysed in this paper, was submitted by two groups of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv students who specialise in philosophy. Group 1 is a group of third year students, which comprises 11 female and 6 male learners (n=17), Group 2 is a group of second year students, made up of 14 female and 5 male learners (n=19), both groups (total n=36) are of B1+/B2 level of English according to CEFR. The groups were selected for my research because of 1) the proximity of their level of English and their university studies background, which contributed to the objectiveness of their results interpretation; 2) a fairly large number of students in the groups, which provided me with broader sample material; and 3) a friendly rapport established with the groups, which led me to believe that the students would be willing to give their consent to participate in the study.

Ethical considerations of the study. At the end of the semester the students were informed of my intention to use the tests they turned in for the purposes of my investigation. To ensure that the validity of the research would not be questioned, the potential participants were advised about the purpose and procedure of my study. I did not disclose my plans to the learners before assigning the tests to them to avoid possible effect of such prior knowledge on the outcomes of my experiment. The students were advised that their names would not be disclosed in the paper, and they were free not to give their consent with no further academic consequences. All the learners gave their oral consent to participate in the research. The study was conducted based on the objective assessment of the written work handed in by the students, with the uniform criteria applied to all the submitted tests. There were no participants specially selected for my experiment, which ensured the objectivity of my investigation and the representativeness of the sample.

Instruments and Procedure: The written work that features in the article is part of the module tests submitted by the two groups and is subject to the analysis in respect to the number of idiomatic formulae employed by the students in their texts. The quantitative method was used to calculate the number of target lexical items in the learners’ written output: the multiword units that fell under the definition of Miller (2020), demonstrating a degree of fixedness, figurativeness, and opaqueness, were identified in the learners’ writing, and then their idiomaticity was double-checked in the Camrbidge dictionary (https://dictionary.cambridge.org). The number of idiomatic expressions was calculated in every submitted test and then its occurrence per million words was statistically analysed to compare it to the rate of the usage identified in the British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus and in Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (MICASE); or its occurrence per 10,000 words was calculated to compare it against the rate identified in the University of Michigan corps of academic written texts (MICUSP). The qualitative method was used to assess the stylistic appropriateness and formal accuracy of the target vocabulary employed.

The module test (MT) comprised a written part which contained six philosophy-related questions, out of which the students had to choose four and write reflective answers of about 150 words each. Although at times the learners’ answers would slip into a more informal register, overall the test was supposed to be written in a style adhering to the norms of academic discourse.

Group 1: The first MT was done by the third year students (Group 1) around midterm, with no idiomatic expressions explicitly covered in any lessons taught to this group prior to the test. The second MT was done closer to the end of the semester with two classes taught in the second half of the semester that discussed General English (GE) idioms and Academic English (AE) idioms.

The idioms picked up for the GE class comprised: you can’t have your cake and eat it, the game is worth the candles, to lose the thread, to break the mould, to pass the buck, to spill the beans. The lesson plan included the task of guessing the meaning of the idiom by matching it with the possible definition, jigsaw reading in groups into the history of the origin of three of the idioms, and inventing in groups the history of the other three idioms, and finally comparing it to the real story behind them. At home the students were asked to do an output task by picking up two or three idioms that a person particularly liked, write a small paragraph about their personal experience to illustrate it and send it to my email to get the feedback from me. About half of the group completed the output task.

The idioms addressed in the AE class were part of a more general discussion on the use in the academic discourse of the vocabulary which is generally believed to belong to a more informal register. In the lesson we looked into the phrasal verbs which are frequently encountered in scientific articles (e.g. to center round, to focus on, to draw on, to point out, etc.), as well as into some idioms that I came across in the real articles I read for my own research: in the same vein, look at something through the lens of, the return on investment (in the sense of the outcomes of an activity), to get a grip on smth, to shed some light on smth, to give a picture of smth. As a lead-in activity the students were asked to think what concepts could be primarily conveyed by idioms in academic discourse (i.e. the perspective from which a question under study is viewed; discovering/ revealing/ demonstrating/ realizing something, etc.; in other words, idioms act like discourse markers that add expression to the authorial voice). After that, six target idioms were presented to the students with one word missing in each, the learners then had to fill in the expressions with the right word chosen from the list of the missing words provided in the task. After filling in the gaps and discussing the meanings of the idioms, the students were given sample paragraphs from the articles with the target idioms missing from the text and had to restore the paragraph to its original form. At the final stage of this part of the class, the learners were asked why they think the idioms are used in academic discourse, what features they impart to the text that make them a valuable asset for a researcher. The students were given no output task as homework in this academic English class.

It should be noted that the original idea of offering the learners a gap fill task with choosing the right word to fill in the idiom from a multiple choice of words was dismissed given the findings cited by a number of researchers (Boers et al., 2014; Boers et al., 2017), according to which this type of exercise can lead to the undesirable learning of erroneous collocations and thus to the “unlearning” of idiomatic expressions, when students who initially produce the idiom correctly, can then replace the target word with the wrong one as a result of the multiple choice exercise they were subjected to.

Group 2 (Control Group) The group of second year students acted as a control group, with no classes focusing on figurative language that semester. Their written work used in my paper was the second MT they wrote at the end of the semester.

Results and Discussion

Results: Group 1, which comprised seventeen learners, turned in the total of sixteen tests – one student failed to submit their written work. In MT1, conducted in the middle of the term, three students in the group used the total of three expressions that could be attributed to idioms based on Miller’s (2020) definition – actions cannot be seen in black and white, to get the point across, and the truth in the last instance. The last expression is also rather not an idiom characteristic of the English language but sounds more like a direct translation from Ukrainian or Russian. Despite its unnatural form, I still counted it as an instance of idiomatic language, as I was primarily interested not in the correctness of the usage as such but the very attempt to employ an idiomatic expression in university writing.

The second test written by the same group saw the growth in the number of students employing idioms from three to seven, with two learners using the maximum number of idioms in the two tests (3): both of them employed one idiom in the first test, and two in the second one (one GE, one AE). Another noteworthy fact is that in the second test the students did not use any idioms other than those discussed in the classes preceding the test. Out of the six idioms we covered in the GE class, the students used three: you can’t have your cake and eat it; the game is worth the candles; to break the mould; out of the six from the AE class they used two: through the lens, in the same vein. In the texts of three students the former sounded as “through the lens”, while one student used the “through the prism” version of the expression, which sounds closer to the student’s L1 variation. For the results calculation both versions of the idiom were viewed as the same expression.

The most popular idioms encountered in the test proved to be those from the AE class: through the lens/prism used 4 times; and in the same vein 3 times.

As for the control group (Group 2), there were three idioms identified in the tests turned in by seventeen students: to go with the flow, (people just) didn’t buy it, at the end of the day. The frequency of idiom use featured in the tests by Group 2 is comparable to that produced by Group 1 in their first test (3/17 vs 3/16).

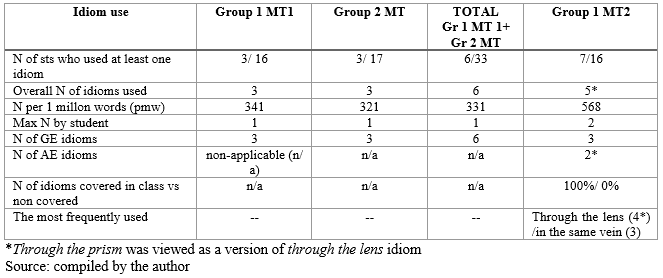

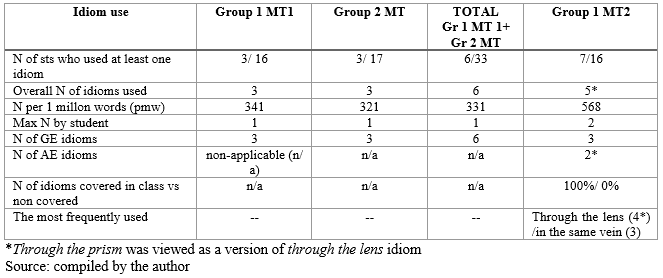

The results of my findings are shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Idiom use in the writing by Group 1 and Group 2

A point of my interest was to compare the rate of idiom use in the AW of Ukrainian students with that of students of an English-speaking university.

If to estimate that one student’s test contained on average 500-600 words, then we obtain the frequency of 6 idioms per 18,150 words (550 words by 33 sts) in the control AW of both groups, i.e. done with no idiomatic language taught prior to the test, which amounts to approximately 331 idioms per million words (pmw): 341 pmw in Group 1 and 321 pmw in Group 2. This outcome is comparable to the findings cited in Miller (2020): 327 idioms pmw identified in the British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus, and higher than the results recorded by Simpson and Mendis (2003): 260 pmw in Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (MICASE). The frequency of 568 idioms pmw demonstrated in MT2 of Group 1 is not comparable to these findings as it was affected by the teaching of idiomatic language prior to the test.

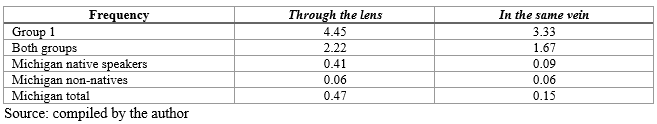

For the purpose of assessing the individual idiom use I turned to the site of the University of Michigan Corpus of Upper-level Student Papers (MICUSP, 2009), which contains the corpus of 800 A grade papers (approximately 2.6 million words) of various kinds (essays, critique, reports, etc.) and across different disciplines. This site attracted me by its accessibility, the possibility of dividing writing into that produced by native and non-native speaker students (although the amount of writing by these two categories of students might not be identical), and the relative simplicity of search parameters. The idioms which were most frequently used by Ukrainian students were through the lens and in the same vein, discussed in the AE class. The search of their usage in MICUSP yielded the following results:

These findings are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Top two idioms used by Ukrainian sts vs their usage recorded in MICUSP (per 10,000 words)

Discussion: One of the aims of my research was to discover if idiomatic language indeed occurs in the academic texts of Ukrainian university students, written in English, and if so, how the rate of idiomaticity correlates with that exhibited by the students of English speaking universities; another aim was to find out if the discussion of idiomatic expressions in the classroom affected the frequency of idiom use demonstrated by the learners.

In the written tests, submitted by the students, the number of figurative expressions, which fell under the category of idioms, was calculated in every test and then its occurrence per million words was analysed to compare it to the rate of the usage identified in the British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus and in Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (MICASE); or its occurrence per 10,000 words was calculated to compare it against the rate identified in the University of Michigan corpus of academic written texts (MICUSP). Unfortunately, I could not find the research that would identify the general frequency of idiom usage in the corpus of academic written English, therefore only the individual idiom use could be compared against the statistics available for written academic texts.

My findings show that the students’ writing indeed features both idioms and metaphors even in the tests done in the classes not preceded by explicit discussion of figurative language in the academic context: in such tests both groups employed three idioms per group (one of 16, the other of 17 students).

In the second module test, written by Group 1 after classes that addressed metaphorical language use, the learners used solely the idioms we had covered in the classroom: three out of six covered in the GE class, and two out of six from the AE class. The frequency of idiom use in MT 2, which turned out almost twice as high as that displayed by the students in control tests (568 idioms pmw vs 331 idiom pmw), appears to confirm the hypothesis that discussing idiomatic language in class does affect the learners’ productive output, even when they are not explicitly asked to use the target vocabulary in their writing.

It cannot be stated with certainty why this particular number of idioms was used or why the rate of GE idioms usage was higher than that of the AE. I could only assume that the idioms the students chose are either close to the expressions that they have in their L1 in terms of concept and form, i.e. demonstrate a high degree of “congruency” (e.g. through the lens/prism, in the same vein, the game is worth the candles), or are based on a vivid image, which may prompt the idiom’s easier recall (e.g. break the mould, you can’t have the cake and eat it). These outcomes are in line with the findings cited by Peters (2016) and Snoder (2017), who maintain that congruency is a factor which affects the acquisition of formulaic sequences by learners, with incongruent collocations proving to be more difficult to learn than congruent ones. One of the reasons for non-usage of the rest of the idioms could be that they were not particularly suitable for the questions that the learners reflected on, or – in the case of the AE idioms – were more appropriate for a research paper rather than for this kind of reflective writing.

The strongest students, who tend to intentionally learn the vocabulary we discuss in class and often demonstrate their uptake in later lessons, predictably employed the most idioms in their writing. Out of the three students who used idioms in their first test, two used the highest number of idioms –two – in the second test as well. Interestingly, all the idioms in MT 2 occurred in the writing of seven students (less than half the group), which might be interpreted as an evidence in support of Simpson and Mendis’ (2003) observation, who argue that the use of idioms seems to be more a characteristic of an individual learner’s idiolect than that of a certain linguistic or content-related field.

Apart from idioms, the second test of Group 1 featured a number of metaphors, e.g. “it’s a life path I follow every day”, or “art opens the veil of something bigger to us”. Generally, the second test submitted by the group produces the impression of being more loaded with figurative language, which could also perhaps be attributed to the fact of having explicitly discussed idiomatic language in class and therefore raised the learners’ awareness about the potential of its usage in university writing.

As for Group 2 (control group), there were three idioms identified in the tests turned in by seventeen students, the number comparable to that exhibited by Group 1 in the first test (3/16 students vs 3/17 students), with the difference that the idioms used by Group 1 belong rather to the neutral register, while Group 2’s sound rather informal. The style of Group 2’s writing resonates with Shin’s (2019) observation that L2 student writers tend to rely on formulaic language typical of conversation more than native-speaker academic writers do.

Another remarkable finding is that a lot of students of the control group demonstrated the use of metaphors in their tests: 11 students out of 17 used at least one metaphor in their writing, with one student going as high as six. Most of them had to do with one of the most common metaphors underlying academic discourse – that of serving as a basis or origin for something: the words and phrases foundation, footing, “fundament”, stems from, roots of, cornerstone featured highest on the list of the metaphors employed. The reason for it could also be that in the classroom we discussed on several occasions how important it is to enrich one’s language with synonyms to the word “basis”, which students tend to overuse in their speaking.

Surprisingly, even in the tests supposedly uninformed by previous learning of idiomatic language, the rate of its usage by Ukrainian students (331 idioms pmw) appeared to be higher than that cited by Miller (2020): 327 pmw; and Simpson & Mendis (2003): 260 idioms pmw. A somewhat higher rate of idiom usage in the control writing may be attributed to the fact that the AW, analysed in my research, belongs to the students of humanities who, according to Miller (2020), tend to employ a higher amount of figurative language in their productive output. The unnaturally high frequency of idiom use in MT2 of Group 1, both overall (568 idioms pmw) and that of individual idioms, might have been caused by the specific conditions affecting the AW, as the learners could have wanted to obtain higher marks for the tests due to the use of idiomatic language, which we had discussed in the classroom. At the same time the high frequency of individual idiom use seems to support the line of argument formulated by Simpson and Mendis (2003), who point out that, unlike non-native speaker’s frequency of idiom usage, the rate of occurrence of any individual idiom in texts by native speakers is indeed quite rare and unpredictable, which is caused by a vast repertoire of idioms that native speakers possess.

Pedagogical Implications: The Ukrainian students who participated in my research displayed a higher rate of idiomatic language use than their American and British counterparts, which turned out to be the most unexpected finding of my study. At the same time, all the idiomatic expressions employed were encountered in the tests of the “top performers” of the groups, whereas more than half of Group 1 and over 3/4 of control group failed to use any idioms at all. Another important finding is that Ukrainian students – although they might be quite skilful at carrying across their overall idea – remain more often than not fairly insensitive towards the stylistic characteristics of the vocabulary they use, which was vividly demonstrated in the writing of the control group. Given these findings, it could be beneficial for students if explicit teaching of idiomatic language were included into their university AW courses, with special attention paid to discussing the stylistic features of the idiomatic expressions appropriate for academic discourse, and the functions that idioms can perform in academic texts. This could lead to raising the students’ awareness of the conventions of constructing academic texts in English, and consequently to enhancing the quality of their AW.

Conclusions

Figurative language, which may appear to be not entirely in line with accurate and straightforward formulations of academic discourse, is worth discussing in AW classes to raise the learners’ awareness of the potential of its use in the academic context. Although the most surprising finding of my research was that the Ukrainian students’ frequency of idiom usage turned out higher than that of their American and British colleagues, there still are many issues to be addressed by English instructors, when it comes to teaching AW courses to Ukrainian learners. For example, the fact that all the instances of idiomatic language occurrence were identified in the writing of fewer than half of students in the groups, with the rest of the learners having used no idioms at all; or the common unawareness of the register of the vocabulary the learners use and their tendency to slip into informal style, which disrupts the conventions of academic writing. Overall, despite the fact that an explicit or intentional way of teaching idioms may lead to a somewhat exaggerated way of employing them in the productive output, in the long run it is likely to benefit the learners both in terms of knowing the concrete idioms, suitable for the academic context, and generally of promoting the learners’ acceptance of the fact that metaphorical language can function quite organically in academic discourse.

The present investigation was subject to certain limitations, among which the amount of the written output analysed for the purposes of my research. Although it could be concluded that Ukrainian students do use idiomatic formulae in their academic writing, done in English, the amount of writing that features in my study is too small to make any large scale conclusions about the actual frequency of idiom use by large numbers of Ukrainian students of various specialisations. Another limitation has to do with the level of English of the groups, whose tests were assessed, and with their specialism. Both groups are of B1+/ B2 level of English language proficiency, specialising in philosophy, and it could be assumed that they might employ metaphorical language more freely and more often than learners of a lower degree of proficiency or of different (e.g. technical) specialisations.

Therefore, the potential for future studies lies in broader research that would involve larger numbers of students of various specialisations and different levels of English proficiency to have a more objective picture of the specifics of their idiomatic language acquisition and use. On a more practical footing, further research is called for to investigate the most effective methods of facilitating the acquisition of idioms, i.e. holistic vs analytical approach, exposure spacing, etc. to enhance the learning gains. The potential findings of such studies can reveal the patterns of Ukrainian students’ uptake and application of English figurative sequences in their texts, which in its turn will enable the EAP instructors to address the identified drawbacks in designing AW courses and consequently improve the quality of teaching AW to Ukrainian students.

Bibliographic references

Ädel, A., & Erman, B. (2012). Recurrent word combinations in academic writing by native and non-native speakers of English: A lexical bundles approach. English for Specific Purposes, 31(2), 81-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2011.08.004

Baker, M. (2017). In Other Words. New York: Routledge.

Biber, D., & Barbieri, F. (2007). Lexical bundles in university spoken and written registers. English for Specific Purposes, 26, 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.08.003

Boers, F., Demecheleer, M., Coxhead, A., & Webb, S. (2014). Gauging the effects of exercises on verb-noun collocations. Language Teaching Research, 18(1), 54–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168813505389

Boers, F., Dang, T. C., & Strong, B. (2017). Comparing the effectiveness of phrase-focused exercises. Language Teaching Research, 21(3), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816651464

Herrmann, J.B. (2013). Metaphor in Academic Discourse. Utrecht: LOT.

Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (pp. 202-251). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lazar, G. (2003). Meanings and Metaphors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lysanets, Yu., & Bieliaieva, O. (2023). Idiomatic potential of anatomical terminology and its role in developing English language proficiency. The Medical and Ecological Problems, 27(1-2), 29-34. https://doi.org/10.31718/mep.2023.27.1-2.06

MICUSP. (2009). Ann Arbor, MI: The Regents of the University of Michigan. Retrieved from: https://elicorpora.info/main

Miller, J. (2020). The bottom line: are idioms used in English academic speech and writing? Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 43, 100810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.100810

Moon, R. (1998). Fixed expressions and idioms in English: a corpus-based approach. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Oakey, D. (2020). Phrases in EAP academic writing pedagogy: Illuminating Halliday’s influence on research and practice. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 44, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.100829

Park, J., & Chon, Y. (2019). EFL Learners’ Knowledge of High-frequency Words in the Comprehension of Idioms: A Boost or a Burden? A Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 50(2), 219-234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688217748024

Peters, E. (2016). The learning burden of collocations: The role of interlexical and intralexical factors. Language Teaching Research, 20(1), 113–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168814568131

Rahmtallah, E.A.E. (2024). EFL Learners' Comprehension of English Idioms at the University Level. Journal of Education and Practice, 15(6), 24-33. https://doi.org/10.7176/JEP/15-6-03

Ruskan, A., Hint, H., Leijen, D.A.J., & Šinkūnienė, J. (2023). Lithuanian academic discourse revisited: Features and patterns of scientific communication. Open Linguistics, 9(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2022-0231

Shin, Y.K. (2019). Do native writers always have a head start over nonnative writers? The use of lexical bundles in college students’ essays. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 40, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.04.004

Simpson, R., & Mendis, D. (2003). A Corpus-Based Study of Idioms in Academic Speech. TESOL Quarterly, 37(3), 419-441.

Snoder, P. (2017). Improving English Learners’ Productive Collocation Knowledge: The Effects of Involvement Load, Spacing, and Intentionality. TESL Canada Journal, 34(3), 140-164. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v34i3.1277

Stamenkoska, I. (2017). Idioms in the EFL Classroom. Horizon Series A, 21, 85-94. https://uklo.edu.mk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/7.pdf

Szudarski, P. (2017). Learning and teaching L2 collocations: insights from research. TESL Canada Journal, 34(3), 205-216. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v34i3.1280

Ta'amneh, M. A. A. A. (2021). Strategies and Difficulties of Learning English Idioms Among University Students. Strategies, 12(23), 76-84. https://doi.org/10.7176/JEP/12-23-10

Tran, H.Q. (2017). Figurative idiomatic competence: An analysis of EFL learners in Vietnam. Asian-focused ELT research and practice: Voices from the far edge, 66–86. https://leia.org/LEiA/LEiA%20VOLUMES/Download/Asian_Focused_ELT_Research_and_Practice.pdf#page=79

Vongpumivitch, V., Yu, L-T., & Nguyen, T.P. (2023). Distance education project of English idioms learning from watching YouTube. Frontiers in Psychology 14, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1171735

https://amazoniainvestiga.info/ ISSN 2322- 6307

This article presents no conflicts of interest. This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Reproduction, distribution, and public communication of the work, as well as the creation of derivative works, are permitted provided that the original source is cited.