DOI: https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2024.84.12.10

Volume 13 - Issue 84: 167-182 / December, 2024

How to Cite:

Yashchuk, P., & Ryzhov, I. (2024). Vital security: Rethinking human security in the context of hybrid peace. Amazonia Investiga, 13(84), 167-182. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2024.84.12.10

Vital security: Rethinking human security in the context of hybrid peace

Вітальна безпека: Переосмислення безпеки людини в контексті гібридного миру

Received: November 10, 2024 Accepted: December 20, 2024

Written by:

Petro Yashchuk

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9367-0604

Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychology and Inclusive Education, Khmelnytskyi Regional Postgraduate Institute of Pedagogical Education named after Anatoly Nazarenko, Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine. WoS Researcher ID: LXA-5385-2024 - Email: medmil.ua@gmail.com

Igor Ryzhov

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8009-5895

Doctor of Law, Chief Researcher, National Academy of Security Service of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine. WoS Researcher ID: ABC-5271-2021 - Email: igo_rys@ukr.net

Abstract

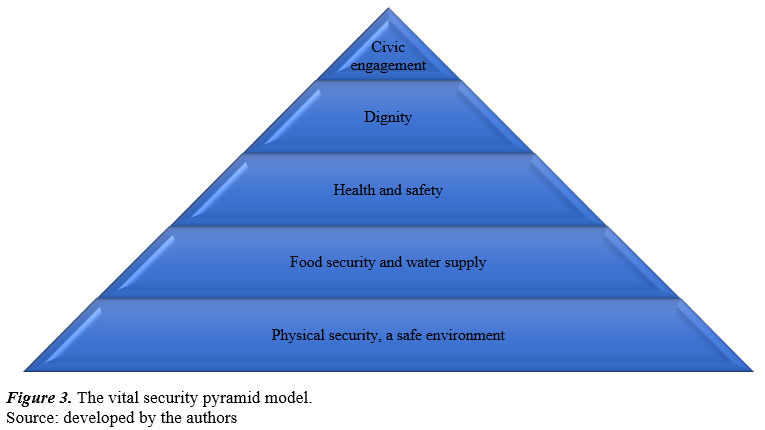

The study's relevance is determined by the fact that in the 21st century, the problem of ensuring the safe existence of a person has not only retained its acuteness but has also become significantly more relevant due to new challenges, dangers and threats that are becoming global. The international community and individual nation-states have yet to develop sufficient answers to these dangers. Ensuring the individual's security (vital security) about the advent of new hazards and threats to his or her essential interests entails the search for innovative ways. The study aims to systematise knowledge in personal security and to conceptualise effective measures to ensure it in the era of hybridity. The study results in formulating a vision of vital security (human security) in today's era of hybridity, particularly hybrid peace. The study's novelty is the proposed LEGO model of the "pyramid" of vital security. The LEGO model pyramid is built according to the principle similar to Maslow's pyramid but with levels of not rigid nature, which can be supplemented and rearranged according to specific (local) conditions of security landscape and security perceptions. Realist and neo-realist concepts of liberal peace have their gaps and weaknesses in the interpretation of vital security, and there is an urgent need to improve the human security paradigm, considering local specifics caused by the conditions of hybrid peace, which implies a constant state of change and reflects multi-level and multi-problematic cooperation and competition. It is shown that, instead of static-type model, inherent in previous eras, today world of hybrid peace actually represents a model of constant dynamism when all factors interact, distorting the activities of others. Human security in the era of hybridity is thus a flexible and multidimensional entity, and paradigm of its essence and functioning should be improved continuously based on Agile and systemic vision.

Keywords: human security, vital security, vital potential, armed conflict, hybrid peace.

Анотація

Актуальність дослідження визначається тим, що у ХХІ столітті проблема забезпечення безпечного існування людини не лише не втратила своєї гостроти, а й значно актуалізувалася через нові виклики, небезпеки та загрози, які набувають глобального характеру. Міжнародне співтовариство та окремі національні держави ще не виробили достатніх відповідей на ці небезпеки. Забезпечення безпеки особистості (вітальної безпеки) щодо появи нових небезпек і загроз її життєво важливим інтересам потребує пошуку інноваційних шляхів. Метою дослідження є систематизація знань у сфері особистої безпеки та концептуалізація ефективних заходів для її забезпечення в епоху гібридності. Результатом дослідження є формулювання бачення вітальної безпеки (безпеки людини) в сучасну епоху гібридності, зокрема гібридного миру. Новизна дослідження полягає у запропонованій LEGO-моделі "піраміди" вітальної безпеки. Реалістичні та неореалістичні концепції ліберального миру мають свої прогалини та слабкі місця в інтерпретації вітальної безпеки, і існує нагальна потреба в удосконаленні парадигми безпеки людини з урахуванням локальної специфіки, зумовленої умовами гібридного миру, що передбачає постійний стан змін і відображає багаторівневу та багатопроблемну співпрацю та конкуренцію. Показано, що замість статичності, притаманної попереднім епохам, сьогоднішній світ гібридного миру фактично являє собою модель постійного динамізму, коли всі фактори взаємодіють, спотворюючи діяльність інших. Таким чином, людська безпека в епоху гібридності є гнучкою та багатовимірною сутністю, і парадигма її сутності та функціонування має постійно вдосконалюватися на основі гнучкого та системного бачення.

Ключові слова: безпека людини, безпека життєдіяльності, життєвий потенціал, збройний конфлікт, гібридний мир.

Introduction

Hybrid threats have become one of the modern challenges to the national security of any state. They reflect significant changes in the nature of international security. In particular, some concepts of hybrid warfare include extensive non-military instruments. Modern warfare to a significant extent is moving from the real world to the virtual world - cyberspace, where a real confrontation between superpowers is unfolding; moreover, war from a purely physical phenomenon is increasingly moving into the spiritual and ideological plane, when modern technologies are used to control mass consciousness. Finally, the global financial and especially banking sectors provide serious economic levers of influence on the states. In addition, hybrid warfare involves the integration of various real and virtual threats (diplomatic, military, economic, informational, etc.) in order to exert psychological influence on the victim state, immerse it in a situation of uncertainty, weaken and destroy it without declaring war, as well as to create an appropriate information field around it, designed to form in the world community such an image of this state that would justify any unfriendly and even aggressive actions against it (Borch & Heier, 2024). It should also be noted that today soft power is being transformed into more latent forms, posing a real and much more significant threat to the national security of the states that are the objects of this power.

In modern conditions, the world is in search of a security system that should provide protection from new threats and challenges in the spheres of democracy, economics, culture, ecology, information, etc. Despite years of upward development achievement, new statistics and research reveal that people’s perception of safety and security remains poor in practically every country, including the wealthiest ones (United Nations Development Programme, 2022). According to recent studies, since 2020, the danger to human security has significantly increased in 43 nations, exposing populations to violence from both state and non-state actors. In the first quarter of 2023, indexes measuring government stability, civil unrest, and conflict intensity showed political risk at a five-year high (Middleton, 2023). Conflicts have been increasing globally, with no region being unaffected, following a decrease in the 1990s and early 2000s. Transnational criminal activity is becoming a bigger factor in these confrontations, which frequently include many sides. Some have persisted for decades, while others have not been addressed by the global community. However, they come at a huge cost, and civilians typically bear the brunt of it. War in Ukraine, involving many stakeholders in its orbit, China’s policy of ‘aggressive soft power’, expanding conflict landscape in the Middle East, as well as climate change, internal political instability in a number of states - all these represent far not full ‘array’ of contemporary threat to vital security. At the same time, the existing theory and modern states’ policies to ensure the security of the individual lack adequate scientific and methodological approaches to defining and protecting the vital interests of the individual, analysing the threats and dangers that affect a person.

Meanwhile, the importance of developing comprehensive strategic approaches aimed primarily at identifying vulnerabilities, as well as including human security as the basis of the entire security system and countering hybrid threats, is obvious. Today, critical research covers non-traditional security theories (Dadwal, 2015). New views on security are based on a departure from the traditional military aspect of security. In modern democracies, the concept of “human security” is increasingly gaining momentum. In essence, this is a kind of transition from a very narrow to a broad understanding of security. At the centre of the new concept of security , there is not the state, but the individual. And while in the past it was believed that thanks to security at the state level, it is possible to guarantee the security of the individual, today this pyramid is turning upside down (McIntosh & Hunter, 2017).

Since the mid-1990s, the concept of human helplessness has been featured in almost all theoretical discussions of the modern approach to security as one of the most pressing issues. Today, after three decades, human security has become a key factor considered in almost all professional and academic works worldwide, based on the well-known position that security is a basic human need, a fundamental human value, and almost guaranteed security. This has become critical in maintaining local, community, regional, and global security. Today, almost no national defence strategy does not pay special attention to human security.

Vital security (human security) has created an extraordinary wave in the epistemological community of international relations in recent decades. Considering the interconnected problems of underdevelopment and human rights, human security expands the scientific approach to include dangers beyond military security by referring to people and their security as a model of IR (Vejnović & Obrenović, 2023). With its emphasis on interstate security rivalry, this perspective constitutes a forceful opposition to the prevailing hegemony-based paradigms within realism and neo-realism. Nonetheless, disagreements exist on this new paradigm's normative character and issues of analysis and explication. Human security professes to give an analytical framework for investigating and explaining security challenges, but it also claims to be a practical guidance that can be applied to foreign policy. This political tendency puts the developing human security paradigm vulnerable to critique from opposing schools of international relations thought.

At the same time, no single definition of human security is observed. UN agencies (Muguruza, 2007), governments, the private sector, non-governmental organisations and academia have all contributed to developing a universal understanding of human security. However, developing a universally accepted definition of personal security has not yet been possible, often leading to its expansive interpretation. It raises the problem of the legitimacy of external intervention and complicates the practice of this area. It was named a new theory or concept, an analysis starting point, a worldview, a political agenda, or a policy framework in the literature on international relations and development. The definition of human security is still up for debate. However, its proponents agree that the focus must be shifted from a state-cantered approach to security to a people-centred approach and that worries about the security of state borders should be replaced by worries about the security of the people who live there (Vejnović & Obrenović, 2023).

"The absence of insecurity and threats" is the most basic definition of security. To be secure is to be free from need (food, employment, and health) as well as fear (physical, sexual, or psychological abuse, persecution, or death). Therefore, detecting dangers, avoiding them wherever feasible, and lessening their impacts when they occur are all part of human security. It implies assisting victims in overcoming the consequences of widespread instability brought on by armed conflict, abuses of human rights, and underdevelopment (Tadjbakhsh, 2005). This enlarged definition of "security" incorporates two ideas: one is the concept of "safety" that extends beyond traditional physical security, and the other is the idea that livelihoods should be protected by "social protection" against unforeseen disruptions.

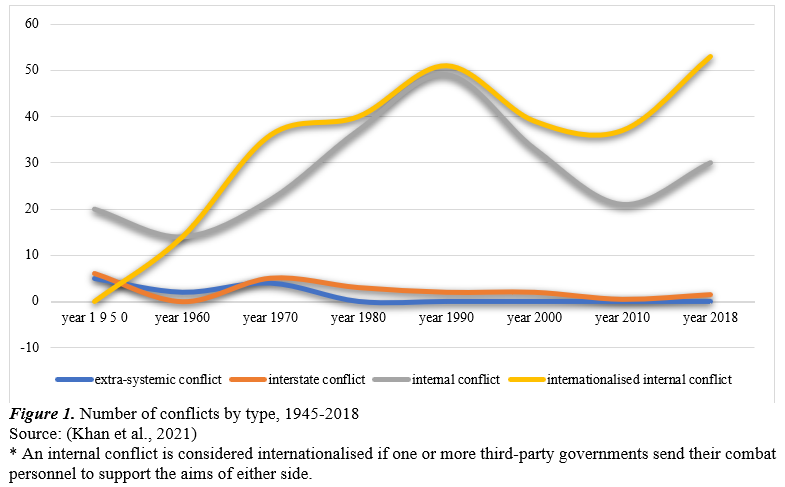

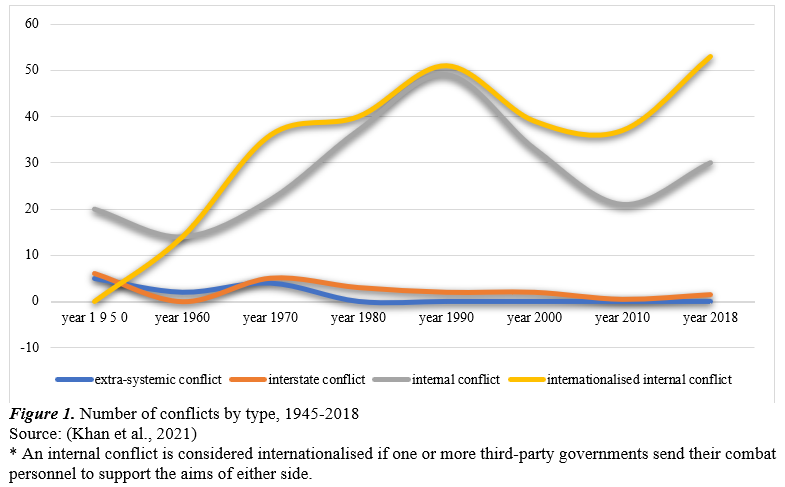

Following the conclusion of the post-Cold War era, empirical research served as the foundation for the development of the notion of human security. Numerous instances of nations turning into insecure actors, neglecting their duties to their citizens, and endangering their existence have eroded respect for sovereignty. In addition, this century has characterised several relatively recent and frequently fruitless foreign operations in Kosovo, Bosnia, East Timor, and Afghanistan. More recently, new hotbeds of geopolitical tension and war have been added to this spectrum of conflicts: the war in Syria, the Russian-Ukrainian war (both in its hybrid stage since 2014 and in full-scale war since 2022), and the war between Israel and Hamas, which has already involved Iran and Lebanon and threatens to expand to other countries in the Middle East. Data from 2018 demonstrate the critical increase in internal and internationalised internal (i.e., essentially hybrid) conflicts since the end of World War II, despite the creation of the UN and the adoption of international humanitarian law (Figure 1).

The number of conflict-related deaths increased by 45% in the year before Russia invaded Ukraine, with more than 100,000 deaths recorded in 2021. Violence escalated considerably in Mali, Ethiopia, Myanmar, and Ukraine. Thus, 2022 became the deadliest year of armed conflict since the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, as well as the worst year in the history of the Global Peace Index (Vision of Humanity, 2023).

Increased geopolitical competition is fuelling conflicts in many countries. Large and medium-sized powers are jostling for influence in states or regions, supporting competing interests by supplying troops and weapons. Drones have also appeared to be crucial arms and played an important role in several wars—in particular, military and commercial drones were widely deployed in Ethiopia, Ukraine, and Myanmar. The overall number of drone assaults climbed by 40.8% in 2022, while the number of groups deploying drones rose by 24% (Institute for Economics & Peace, 2023).

Social crises, especially war, are like a litmus test for modern society's shortcomings and problematic aspects. In such circumstances, the course of conflicts is determined by several conditions that determine the ability to withstand challenges and threats to the national security system as a set of state institutions and non-governmental organisations that function to protect the primary goals of society, the rights and freedoms of citizens from external and internal threats and ensure the ability of each individual to morally, mentally and physically resist them in case of occurrence.

We are living through a period of transition characterised by competing conceptions of power and competing modes of security. Unlike the Cold War and the entire modern period, the combination of new wars and the war on terror undermines many of the norms and laws of war associated with traditional geopolitics, i.e. bombing schools and hospitals, assassinations from a distance, the use of poison as a weapon or beheadings and sexual slavery. It leads to large-scale forced displacement.

Against this background, the basic dimensions of vital security are undergoing significant changes, and studying these new realities is a highly urgent task for scholars and experts. The solution determines the effectiveness of policies and strategies in vital security in a landscape of rapid critical changes and unpredictable new threats both on the scale of individual states and at the regional/global level.

The theoretical, practical and political significance of rethinking the generally accepted discourse of the concept of human security in such conditions is to determine the referent of vital security, its place in the multidimensional construction of national security, and to outline the content of the concept of human security, where the object and subject of security are entirely concentrated on the person himself. This publication aims to systematise knowledge in the field of personal security and to develop effective measures to ensure it actualises the development of vital security as a private theory.

Literature Review

Levels of human security and vital security domain

Even though there are several global indices used in attempts to define and quantify human security (such as the Failed State Index, Global Peace Index, Human Development Index, and Bertelsmann Transformation Index, to name a few), none of them, at least not yet, accurately reflect the state of human security because they are designed for different purposes. Other attempts to evaluate the state of human security throughout the world have been made (such as the Human Security Index), but they approach the problem from a different analytical angle and primarily focus on substantiating human security through an equitably increased Human Development Index.

Meanwhile, Ahmadzai (2020) rightly argues that human security is an interdisciplinary field that conceptualises security from a multidimensional perspective. Unlike other security and policy frameworks, the basic human security analysis unit is people or individuals. Human security reveals the various threats faced by people around the world. Having an objective to comprehend and mitigate these threats, human security offers various theoretical applications. It is a new paradigm which arose within the political order of the post-Cold War world.

Vital security in the overall human security landscape is generally understood as prioritising people's security, especially their wellness, safety and well-being, over the security of states (Gebre, 2015). Human security ‘advocates’ argue that, for example, poverty, hunger, population displacement, social exclusion, disease, and environmental degradation directly affect human security and, thus, global security (Singh, 2016). They lead to the death of far more people even than the combination of wars, genocide and terrorism. Thus, recognising that development, peace, security, and human rights are interconnected and mutually reinforcing is implicit in human security. The definition of the human security domain remains a debate between ‘broad’ and ‘narrow’ approaches to human security as if they were separate. Each approach emphasises a different "side" of human security: the broad (freedom from want) - development agenda and the narrow (freedom from fear) - human rights agenda.

Historical retrospect and philosophical foundations of human security

Human security has gained significant traction and recognition in the post-Cold War period. Over the past two decades, the basic ideas of human security as a general political orientation have gradually become mainstream in international relations.

Realist critics of human security argue that states are primarily interested in their security and generally do not care about the "fear" or "need" of others unless core national interests are at stake. Consideration of human rights plays, at best, a marginal role in the grand game of power politics in the context of international struggles for security, power and position. Consequently, since human security does not contribute to the state's national interest, it can be dismissed as an irrational and even risky adventure emanating from the sometimes idealistic human mind (Schütte & Fordelone, 2006). The growing criticism of realist conservatives within the US Republican Party of the neoconservative policies of the Bush administration, which set the promotion of liberal democracy around the world as a strategic goal, reflects this rejection of a normatively laden foreign policy aimed at spreading liberal democracy around the world: "As we wage war today to protect the world from terror, we must also work to make the world a better place for all its citizens", wrote Toft (2005). Two prominent realist scholars, J. Walt and S. Mearsheimer, took a clear stand against this understanding of American internationalism, especially against the intervention in Iraq. They argued that, while the US would almost surely win such a battle, an armed struggle with Iraq would distract resources and focus away from the more essential goal of removing the terrorist threat. In sum, the invasion of Iraq is the wrong war, in the wrong location, and at the wrong moment (Walt & Mearsheimer, 2006). This view of international relations, which is most clearly outlined in Waltz's Theory of International Politics, is based on the theoretical assumption that states have a rationally derived and objectively identifiable national interest. One can see that the realist discourse within the IR domain is primarily concerned with promoting the national interest or, in economic terms, how to maximise the state's utility.

Meanwhile, the orientation proposed by Human Security is a decisive challenge to the contemporary realism and neorealism hegemony-based paradigms. Scholars today argue that applying human security as a foreign policy position is not inconsistent with pursuing national interests but depends on different normative predispositions and the political definition of what constitutes a national interest (Hanlon & Christie, 2016). In the case of the European Union, human security, regardless of the nation-state, has already become a tacit position among European states. Therefore, refuting the alleged contradiction between the Human Security agenda and the promotion of national interests is essential.

Dimensions and ‘variables’ of personal security

Gasper and Gomez (2015) emphasise 'personal security' in human security thinking and practice entering into discourse as part of a failed attempt to divide security concerns into compartments. The authors examine the attention to 'personal security' in recent years, both in compartments that address organised physical (tangible) aggression or dangers to one's property and safety ('citizen security') and in broader research on threats to basic needs and rights, such as the comprehensive mapping studies conducted in different reports or research from the UNDP concerning national and regional human development, devoted to women's security. The article reflects on the challenging process of opening up traditional security thinking and practice in ways that allow complementing value and depth without being compressed into preconceived silos. Such studies open a discussion on a structure of human security and contribute to bringing clarity to vital security as its crucial layer.

Asmussen's (2014) study focuses on the impact of the 2014 Ukrainian crisis on international conflict management and human security in the context of "hybrid wars" and unrecognised states. The author analyses the peculiarities of the international community's resolution of conflicts involving multilateral actors. Human security issues are challenging to address when war takes on hybrid forms, and the main actors are unrecognised actors who are not members of international organisations. Asmussen (2014) argues that the Ukrainian crisis has led to the revival of the OSCE as the main forum for conflict resolution efforts. Mutual respect is a prerequisite for establishing a new European peace order that ensures human security. At the same time, evidence shows arising of some entropy tendencies in European security common understanding, and this fact should be also taken into account when analysing consequences of the war in Ukraine for European security landscape ‘design’.

In addition, several scholars argue that environmental change can threaten global, national and human security. According to Khawas (2014), environmental challenges include managing and distributing natural resources (such as oil, minerals, and forests), land degradation issues, climate change, water quality, and quantity. These variables may directly contribute to violence or may exacerbate existing reasons, such as poverty, migration, illicit small arms, and infectious illnesses. Water shortages, natural disasters, decreased agricultural productivity, increased frequency and severity of infectious diseases, and changes in human migration are just a few of the massive physical and social changes that climate change is expected to bring about. According to Adger et al. (2021), these changes could significantly impact international security by increasing competition for natural resources, upending fragile states, and intensifying humanitarian crises. However, according to Gan (2024), managing environmental and natural resource issues can also build trust and promote peace via cooperation across tension lines. Thus, the role of security variables is not rigid and once defined, but is characterised with mutually competing vectors.

Societal layer of human security

A wide range of social issues is equally important. Scientific and technological progress may affect human security. Communities with varying access to new technology may experience "future shock" as a result of the global information society's development. Moreover, this development can create new categories of social exclusion and criminal acts such as cybercrime (Estrada-Tanck, 2016). Researchers argue that gender concerns, especially in societies based on a patriarchal paradigm where women's social position is changing, can lead to conflict. However, such issues will likely signify social development (Gilder, 2022).

Krause (2013) explores the significance of personal safety and security, which is why this area of study rightfully has a prominent position and why, since 1994, security sector reform has become a key component of many facets of foreign policy and development aid. However, he tries to go further: "Many of the issues that fall under the UNDP's or the Commission on Human Security's adopted concept of human security have thus been sidelined (e.g. health or food security)" (Krause, 2013, p. 84). Indeed, much of what goes under the name of "human security" in the European and North American governments and international agencies he examines is focused on controlling physical violence.

Human security approaches to these risks to personal security posed challenges for existing security narratives by concentrating on individuals and allowing for more nuanced depictions of the human being, both physically and emotionally. The emphasis on the psychological and subjective makes the function of 'framing' and human biases in risk perception critical in future research, as well as insights sources that may help to open up security thinking.

An analysis by UN Women (2022) shows that human security, including health and social protection, is less likely to be a priority in conflict-affected countries. In 2019, nearly a quarter (24 per cent) of public spending in Afghanistan was on defence, with another 13 per cent going to 'public order and security'. In contrast, less than 6 per cent of public spending was directed to the health sector, about 9 per cent to education and just 4 per cent to social protection (including all programmes targeting families and children). In Burkina Faso, a country experiencing moderate conflict, the government allocated 10 times more to defence than to social protection (including all programmes marked as targeting families and children) in 2020.

NATO’ vision of security.

The intrinsic interdependence of many risks and values makes it difficult to categorise security into distinctly distinct categories: "personal" vs "economic" and "health." Proper interaction with genuine human-environmental ("socio-ecological") systems necessitates fewer rigid pre-established divisions and benefits from the flexibility of human security.

Birch (2024) notes that NATO's Strategic Concept 2022 and the Human Security Guidance document reflect the new focus that the Alliance have made on strategic competition, the threat of Russian war in Europe, and a more holistic approach to security. In addition to its general outlines and guiding vision, Strategic Concept 2022 adopts several specific assessed challenges formulated in Strategic Concept 2010. The 2022 Strategic Concept reaffirms the special concern of the Alliance regarding terrorism. In particular, the Strategic Concept calls terrorism "the most direct asymmetric threat to the security of our citizens and international peace and prosperity". This attitude implies that NATO will continue to focus on an area that has piqued its interest since 9/11 and has been a source of success for the alliance.

Paillé et al. (2022) write that, for the first time, the Strategic Concept 2022 emphasises human security's critical importance, mentioning the "cross-cutting importance of investing in human security and the Women, Peace and Security agenda across all core tasks." For NATO, the approach to human security is to "integrate comprehensive population security considerations into all phases and levels of operations" to prevent and respond to risks to all people, especially in situations of conflict or crisis.

General concerns of human security

The UN and international and national civil society institutions are focused on finding the best approach to identifying the root causes of risks and vulnerabilities people face, also naturally emphasising the need to develop and implement comprehensive responses to sound sophisticated challenges in communities, countries, or regions. Research priorities are usually given to proactive prevention technologies, the creation of mechanisms for early warning of threats, minimising their impact and eliminating negative consequences. Researchers of the evolution of the human security concept have formulated many author's versions of its security discourse (Skulysh, 2023), which is based on Human Security. However, the vast majority of scientific research is devoted to a comprehensive study of the theoretical foundations and principles of building modern mechanisms to ensure human security as a capability of the state healthcare system. In contrast, the problems of a person's ability to independently build a system of natural and proactive protection against existing and future challenges and threats of a mental, informational, psychological, social and physical nature remain unaddressed.

Methodology

The study's theoretical basis is systems theory, the theory of global-local interactions, the general theory of national, international, and global security, the theory of the state, theories of dependence, theories of values and interest, and theories of influence. The research methodology is qualitative and based on content analysis.

Qualitative nature of research is determined by the scattered essence of various human security indices and lack of objectivity of statistical data in this field due to complex and often latent influence of various factors. At the same time, in view of existing array of studies considering issues of vital human security from various angles, content analysis seems to be the optimal research tool. The choice of methodology within systems theory paradigm is determined by the complex nature and ambiguity of the object under consideration (vital human security), as well as the system emergence phenomenon among the subsystems of human security.

The methodological toolkit is formed by the technologies, principles, procedures, and research methods within the political science domain. It widely uses such approaches as comparative and retrospective, dialectical interconnection and interdependence of social phenomena, and the above-mentioned systemic approach. The retrospective approach is used to analyse the evolution of the human security paradigm after the end of the Cold War and during military conflicts of the 21st century. The comparative approach was used to analyse narrow and broad approaches to human security and outline a realist critique of Human Security. Social phenomena' dialectical interrelation and interdependence are utilised to study the nature and characteristics of hybrid threats and peace. The systematic approach is used to analyse vital security components in the hybrid peace landscape and build its pyramidal model.

The general philosophy of the research is constructivism, in which cognition is perceived not as a simple reflection of the world but as an active construction of its model by the subject.

Observing ethical principles of research is ensured, namely the absence of any influence of authors’ possible biases and subjective opinions is ensured, to provide impartial analysis and ensure formulation of objective conclusions.

Results and discussion

Vital security concerns individuals’ and communities’ security rather than nation-state security. It integrates human rights and human development. Vital security is often seen as a 'soft' policy in security, combining physical and material security (Kaldor, 2006).

Human security analysis considers threats to realising fundamental values in people's lives. It strives to reorient the use of the prioritised concept of 'security' to ensure the basic needs of ordinary people are met. Therefore, to the question "whose security?" it answers: "Each of us and all of us". When considering the next question, "security of what?" some forms of human security analysis have become compartmentalised, trying to discuss separately "personal security", "economic security", and "environmental security". This satisfies established disciplinary and bureaucratic criteria and may be helpful. It is frequently ineffective, however. A large portion of the added value of human security analysis comes from serving as a framework for flexibly bridging these divisions according to the particular situations’ nature rather than giving new formulations to topics already addressed in the frame of existing bureaucratic and disciplinary mechanisms. This is because many critical threats arise from the interrelationships between various aspects and forces in particular situations. At least occasionally, an interdisciplinary, holistic perspective is necessary to see the connections and make comparisons between "sectors" to prioritise the most pertinent threats to a particular time and place. This is because the focus on how people live and can live and the function of covering priority values and threats all require this approach.

The leading cause of fear for citizens of highly developed, industrialised nations is no longer the possibility of external assault. Instead, there are worries about organised crime, terrorism, or the acquisition of WMD by rogue states or non-state entities that support terrorism. These worries are frequently articulated in terms of immigration-related anxieties. However, border controls cannot prevent these new sources of insecurity. Instead, they must be addressed through a commitment to overcome modern conflicts, which M. Kaldor (2006) calls "new wars". The new wars represent a fusion of wars (that is, political-nature conflicts between organised groups), violations of human rights, and organised crime.

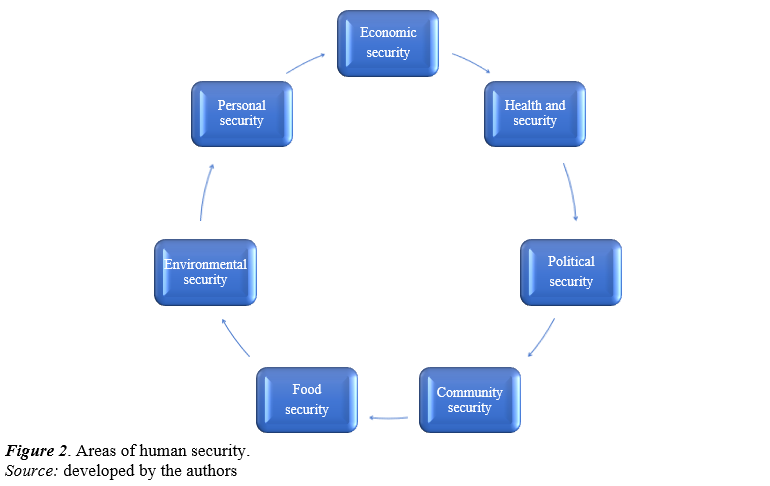

The 1945 UN Charter and previous debate streams emphasised the multiplicity and interconnectedness of core values and corresponding threats. These post-World War II concepts, inherent in the 1940s, were then revised and rethought for the post-Cold War era, leading to the emergence of the human security discourse in the 1990s. It has often used the 1940s language of 'freedom from fear', 'freedom from want' and 'human dignity' - hence also 'freedom from outrages to dignity' - emphasising how these are interrelated. To help move beyond such broad language and support the necessary context-specific analysis, the 1994 Global Human Development Report (HDR) introduced seven dimensions of human security - economic, food, health, environment, personal, community and political - which is the subject of this collection of documents (UNDP, 1994, pp. 24-25). It is primarily a list of values, presented as a checklist for reviewing the relevant threats to these values, as the report does. For the most part, the 1994 HDR was related to recommended strategies for advancement in threat management. Many of the dangers described span numerous value domains, and all value domains impact people's lives. Other than for bureaucratic or academic convenience, there is no justification to consider any value domain separately. Indeed, the 1994 HDR did not propose a list of seven criteria as the sole or adequate basis for thinking about human security. It noted that the categories are interconnected and overlapping and do not address all important concerns.

Some categories were in the early stages of development, and there was neither time nor need to fine-tune them in the report. "Personal security" covered safety from physical violence from other crimes against life and property, as well as from accidents, abuse (including self-harm, e.g. by drugs) and neglect; "economic security" covered housing, in addition to employment and income, which could easily be a separate category; the discussion of "community security" included inter-communal conflicts, indigenous peoples; and "political security" referred to respect for "fundamental human rights", presumably referring to basic civil and political rights. At most, the list presented the myriad of relevant issues reasonably orderly, using categories that could be linked to existing policy portfolios. Most categories can be primarily adapted to existing discourses and policy portfolios, such as food, environment, health, and civil and political rights. This was less the case for 'personal security', given its broad scope and the familiar concern of existing security agencies with the security of state interests, property and the self. 'Community security' also was not adequately defined or reflected in existing portfolios, highlighting its political controversies.

Using a checklist of standard questions concerning "security" was crucial: Whose security? Who perceives security? Security of what values? Against what threats? Who provides security? To what extent? By what means?". While each category in 1994 HDR is related to human security, they do not all have equal weight. Food security and environmental (ecological) security are inputs or instruments for health and other priority values in people's lives; thus, the 1994 environmental security discussion in the WDR focused on specific distinguishing risks rather than a separate environmental values array. And because the seven areas are defined by different questions/criteria, they overlap significantly.

The word 'human security' appears more than 2,400 times in the new Routledge Handbook of Human Security by Martin and Owen (2013), but 'personal security' appears just three times; it has not been replaced by 'citizen security,' which even does not appear at all. Comparing, one can see that the other frequencies: food security 20 times, environmental security 8 times, economic security 6 times, health security 6 times, political security 6 times, community security 2 times (some comparable terms are ranked as follows: National Security 136 times; State Security - 33 times; Global Security - 16 times; Military Security 8 times). Thus, none of the 1994 list of seven titles has been adopted in the Handbook, except the older term "food security". This may be partly due to the disciplinary composition of the authors and topics selected but also to the fact that other titles are already in use; some categories (such as the least used terms "personal security" and "community security") have particular problems, and that the inclusive term "human security" better reflects the unity of human life than attempts to divide it.

Whereas thinking about human development has focused on capabilities and the ability to realise well-founded values, human security analysis looks at vulnerability, exposure to risks and adversity, and the ability to prepare for, cope with and recover from threats and harms. It complements the narrower interpretation of human development, which focuses on measuring the capacities of individuals by emphasising (un)satisfaction of basic needs, change and (instability), as well as their causes and consequences for individuals, groups and species (Ahmadzai, 2020).

Hybrid technologies, characteristic of modern aggression, interfere with social processes when certain circles try to influence society by provoking mass terrorophobia, creating distrust, hatred, and outright hostility between social groups. They substitute the natural development of social processes and systems in favour of their own, sometimes adventurous, political views.

That is why the problem of ensuring the preservation of human potential and the mental and social well-being of the nation is gaining global significance, and this task is much more complex than all those declared today in the context of national security functions. The essence of such a mission is much broader than the physical struggle against aggressors who, through violence and threats, affect the stable order of things, encroaching on the security of the individual, his or her rights and freedoms, public security and its main objects - material and spiritual values of society, state security - the constitutional order, sovereignty and territorial integrity (Chernysh et al., 2023).

Alkire (2003) contends that human beings shape human security, a vital core that must be preserved. The word "vital core" is not meant to be accurate; it refers to a minimum or essential collection of tasks relevant to survival, livelihood, and dignity. The phrase "life-sustaining core" suggests that organisations dedicated to human security cannot safeguard all aspects of human well-being. However, they will at least safeguard the centre.

The notion of a "vital core" seems to us to be the basis of vital security, one component of which is health, including mental health.

In particular, the war in Ukraine for almost three years has had a devastating impact on all aspects of people's lives, especially on their mental health. In the context of constant threat, stress and instability, cases of aggression, violence, anxiety and various mental disorders have become more frequent. The situation is challenging among residents of frontline cities/settlements who are almost on the frontline and face the realities of hostilities and their consequences daily.

War is a potent stressor that can cause a wide range of mental disorders, with the most common being stress, depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders. People who live in conflict zones permanently and in the rest of the country during terrorist air attacks are in a state of high anxiety, which negatively affects their mental and physical health. According to the latest data, 77% of Ukrainians have recently experienced stress and severe nervousness, according to the study "Mental Health and Attitudes of Ukrainians to Psychological Assistance during the War" (Gradus Research Plus, 2024), conducted as part of the All-Ukrainian Mental Health Programme. The study showed that the primary emotions that Ukrainians are currently experiencing are fatigue, tension and stress caused by the full-scale war with Russia. According to the survey, the three most common emotions among Ukrainians are fatigue (46%), tension (44%) and hope (31%). Compared to 2023, the proportion of those who feel tension, fear, anger, irritation, powerlessness, frustration, and despair has increased.

Meanwhile, the number of citizens with a firm hope has decreased. The rate of Ukrainians who have recently experienced stress and severe nervousness remained at 77%. When assessing their mental health, 13% of Ukrainians consider it unsatisfactory, 36% - satisfactory, and 51% - at an average level (Fact, 2024). According to WHO estimates, more than 10 million people in Ukraine today need mental health support. Thousands of people need rehabilitation, which is not only a problem of the present- but also a problem for future generations (Levchenko, 2023).

The above makes it necessary to rethink general approaches to the problem of the impact of martial law on the health of the nation, recognising that reducing the problem of vital security to a specific type of-- healthcare activity is too simplistic a solution to this problem and that strategies and measures implemented under martial law have lost their effectiveness. The war has forced thousands of people to flee their homes. The process of evacuation to safer places, the loss of loved ones and the constant feeling of a possible threat carry a significant emotional burden. It provokes stress, anxiety, fear and panic, which is a complex and lengthy process to overcome, especially given the fact that the vast majority of the population was not morally prepared for this method of protecting the population in the event of a threat or emergency.

Our results actually represent a continuation of findings made by Krause (2013) and Estrada-Tanck (2016) about missing important elements in the current concepts of security. Human security concepts applied today in political discourse and scientific community represent a set of individual elements rather than a system of highly interconnected and equally important layers. At the same time, we strongly agree with the experts of Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance (DCAF) (2024), who argue that hybrid security may be very fluid, with the roles and legitimacy of state and non-state actors moving quite often and transactionally. Our study is also in line with Adger et al.’ (2021) and Gan’ (2024) provisions about sequential impact and interconnection of factors influencing human security.

An analysis of the qualitative state of human potential in the country's context complicated by martial law shows the civilian population's threatening moral and psychological state and provides disappointing forecasts for the future. It is important to acknowledge that in the preceding period, insufficient attention was devoted to the establishment of a system of vital security. This encompasses organisational and technological measures for healthcare and actions to guarantee conditions for a certain level of human safety. Additionally, it includes ensuring a sense of security, which can be defined as the psychological security of the individual. This entails a conscious and responsible influence on the circumstances of life to ensure conditions for mental balance and harmonious development. The ramifications of this reductionist approach to the healthcare crisis extend beyond the considerable toll on lives and injuries sustained during armed conflicts and terrorist acts. It also leads to a profound erosion of public trust in the security apparatus, a phenomenon particularly pronounced in regions that have experienced both occupation and liberation. A society that has suffered from large-scale aggression and terrorist activity has the right to demand guarantees that the new (or modified old) model of human security is more reliable. Or, in other words, to demand from the state some guarantee that this system provides sufficient protection not only for physical but also for mental health and will provide reliable protection against destructive manipulative influences on the mind.

Syria has been in a state of chaos since March 2011. According to United Nations reports, the humanitarian crisis in Syria continues to worsen, with increasing violence and the threat of regional spread affecting the most vulnerable populations (UN, 2024). In 2024, Syria's humanitarian situation remains bleak, with 16.7 million people in need of help -, about three-quarters of the population and the most significant number since the conflict began. The ongoing combat in northern Syria, as well as recent strikes on Damascus, rural Damascus, and Homs provinces, have resulted in civilian fatalities, displacement, and substantial damage to essential infrastructure. In northeastern Syria, attacks in mid-January caused the partial or entire shutdown of hundreds of key infrastructure objects, including water supply stations, health centres, and schools. Over a million individuals were allegedly left without power. Worsened access to power, water, and cooking fuel has aggravated food insecurity and malnutrition, particularly among vulnerable segments of society, including children, pregnant women, and lactating mothers (UN, 2024).

However, one obvious danger to human security is sometimes disregarded when calculating the human cost of armed conflict: the depletion of natural resources and, more broadly, the cost of environmental degradation. Daoudi (2020) contends that under the new security system, the environment is not a freely available source of natural resources to be battled over and monetised, but rather the physical variables that shape human affairs and well-being.

The examples of Ukraine and Syria help to reconcile the theoretical provisions of human security with the realities of today, which require a paradigm shift in the understanding of vital security. Based on our research, we can depict vital security areas as follows (Figure 2).

This concept refutes the realist doctrine of Schütte & Fordelone (2006) that due human security’ non-contributing to the state's national interest, it can be dismissed as an irrational and even risky formation born from the sometimes idealistic human mind.

However, it is advisable to consider these areas within the paradigm of hybridity, a term that is now applied to military conflicts and peacebuilding. It is about hybrid peace (Anam, 2018). Liberal peace critics argue that any "incentives" and rewards are illusory and unevenly distributed. They claim that available liberalism has limitations since it is ultimately secularist, puts rights above needs, cannot address significant social disparities, and is connected to territorial sovereignty. They manifest scepticism about the "certainty of disciplinary liberalism" to ensure social distribution: "The poor do not benefit from policies of self-reliance and privatisation of basic needs". Importantly, however, many liberal peace advocates see liberal internationalism as a way to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. In particular, security and stability, as well as strengthening state capacity and governance, are considered prerequisites for the effective delivery of public goods and, thus, poverty reduction, education, and maternal and child health. Proponents of more emancipatory versions/elements of liberal peace try not to view the agents of liberal peace in host societies as mere recipients, supplicants and beneficiaries. Instead, they use a discourse of partnership and cooperation, in which the reciprocal relationship and incentives are not perceived as an unequal economic transaction (MacGinty, 2010).

Hybrid peace is constantly fluxing, reflecting multi-level and multi-issue cooperation and contestation. International players may not always recognise local indicators of resistance or subversion. West-based military, political, and humanitarian organisations frequently have well-developed information "antennae" with institutionalised reporting channels. However, these organisations often lack the anthropological skills necessary to recognise and decipher local patterns of behaviour, which can be subtle and passive.

A last consideration in establishing hybrid peace is the ability of local actors to promote alternate types of peace. Many civilisations have local conflict resolution and reconciliation mechanisms that rely on traditional, local, or customary norms and practices (MacGinty, 2010).

Instead of a static-type model, the hybrid peace can be presented as a model of constant dynamism when all factors interact, distorting the activities of others. The result is a maelstrom of hybridity. Different influences predominate in different situations, on various subjects, and at different periods. It is not true that there is a separate liberal peace that eventually hybridises. Instead, liberal peace is already hybridised by the diverse context in which it lives. The conceptualisation in this model represents trying to capture and explain the process through hybridisation.

Vital security in the era of hybridity is thus a flexible and rather multidimensional entity. However, it can be represented as a pyramid similar to Maslow's. At the same time, unlike the classic Maslow pyramid, the pyramid levels are not rigid and can be supplemented and rearranged according to specific (local) conditions, like LEGO. The basic version of this pyramid is shown in Figure 3 below.

It should also be noted that the essence of the problem of the security referent is to determine who implements security policy and in whose interests. The traditional approach, both in theory and practical politics, assigned the role of the security referent to the state. After all, the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001 and the subsequent period of anti-terrorist campaigns highlighted the "security paradox": the most powerful state in the world was unable to defend itself against the attack, and entire regions became dangerous as a result of anti-terrorist operations. Nevertheless, representatives of traditional paradigms believe that protecting the state is necessary for protecting the individual since, even with numerous non-governmental organisations and civil society institutions, no other entity can regularly ensure the security of society and its members. Unlike traditional concepts of security, in which social systems or groups act as a referent, the referent of vital security is the individual in all the diversity of his or her spheres of existence, and the state and social institutions play a secondary, sometimes negative role.

In the context of martial law, aggression, and transformations of social relations due to humanitarian and social disasters and revolutions, a person finds himself or herself in an exclusion zone and acquires a marginal status. Being on the border of the conflicting parties, a person loses all guaranteed rights and freedoms, as the political entities that provided them are focused on resolving geostrategic conflicts, maintaining political status, statehood or territories, distracting from social and other issues important to the population. The definition of a person as a security referent implies that he or she has mechanisms to neutralise threats, i.e. an individual must be actively involved in ensuring his or her security.

It is reasonable to propose that if healthcare, for instance, is the responsibility of the state and its associated institutions and presents a challenge to the system of governance and is instigated by its imperfections, then it is necessary to implement an effective mechanism to safeguard individuals from the potential consequences of flawed algorithms. Such consequences can have a significant impact on society. It is, therefore, essential to have a robust system in place to protect individuals from the adverse effects of these algorithms.

It is now appropriate to introduce our definition of "vital security". This implies ensuring the viability of a person, which can be defined as a systemic element of the social system that is safe from social conflicts provoked by the mismatch between the progressive growth of social consciousness and the potential of social systems and their management algorithms (that is to say, the level of tension in relations with social regulators). In light of the above, it is necessary to distinguish between the individual's protection system as a subject of vital security and other forms of protection (Naidon et al., 2024).

Vital security can be abstractly represented as a specific social environment model. The idea of the primary constructs was formed by describing its unique subject area as part of the natural world considered within this context. The context here can be understood as the field of study of vital security, an array consisting of theories, ideas, views, beliefs, perceptions, feelings, emotions of people, and moods that reflect the nature and material life of society, the whole social relations system, in particular.

One of the primary constructs of such a model is the concept of the vital security component, structured by the conditions of functioning and levels of causal relationships, in particular, at the conceptual level; these are basic needs - of public goods and social capital, guaranteed rights and freedoms, social evolution and civilisational development, public and social order. At the functional level, these are external relations between a person and the objects and processes of the environment in all possible areas of activity (humanitarian, informational, socio-psychological, political, economic, acmeological and competence). At the basic level, these are the ways of existence and needs of a particular person or a small group, their consciousness (political, legal, moral), the responsibility of a person for their actions to society and themselves, physical and spiritual state, and viability.

The aggregate components comprise the subject area of vital security as a social process. Each component is characterised by a set of objects and processes and a certain number of actors with different views on the subject area's essence.

Vital security, therefore, is the ability of a person to withstand threats from the outside. This is the main characteristic and semantic potential of vital security. It is a tactical or practical aspect of understanding the goal that is supposed to be achieved promptly.

Degrees of hybridity can be identified by acknowledging that social processes, actors, networks, and structures are all hybridisation products. Networks, players, and structures vary in their degree of fixity. This does not imply that they will always remain unalterable. Instead, it acknowledges the existence of cultural hierarchies and places of resistance within the changing geometry of a hybridised world. Strengthening central state institutions is undoubtedly essential, but becoming the main or only focus risks further alienating them to passivity, weakening the sense of local ownership of problems and solutions.

In specific local conditions, according to the hybrid peace model, as mentioned above, vital security appears as a goal that allows for an effective response to environmental challenges while maintaining energy and mobility. The logic of survival is a strategic goal of preserving self-identity as an adequate response to the goals of hybrid aggressions and their inherent manipulative technologies on the physical, emotional, intellectual and semantic levels. Accordingly, vital potential is the ability to survive and thrive under challenging conditions, the main characteristic and semantic core of the concept of vital security.

Core limitation of the study is the lack of human/vital security discussion in regional terms and case-based approach. Although such discussion could bring more clarity to the practical aspects of vital security implementation, the scope of our study does not imply this analysis, since we set a research task to outline general vectors of paradigm shift in manifestation and understanding of human security in a hybrid peace order. Future research, however, should address this gap.

Conclusions

The scientific elaboration of the vital security issue logically follows from the modern concept of human security, which is the subject of research by many scholars and social institutions. The human security approach generates many political implications, criticisms and challenges. The idea's ambiguity, arbitrary nature, and the scope of its threat epistemology pose challenges to it. Realist and neo-realist conceptions of liberal peace have gaps and weaknesses in interpreting vital security, not considering the realities of the hybrid era that has emerged in the last three decades. All of this leads to the conclusion that the human security paradigm needs to be improved, particularly regarding protection from mental or societal dangers.

Our proposed LEGO model of the "pyramid" of vital security attempts to conceptualise human security in the era of hybridity and represents a novel approach to comprehend human security from the standpoint of vital security paradigm. The model is a flexible tool, allowing taking into account concrete local (region- and country-based) conditions, perceptions, and scope of securitization, thus contributing to understanding human security in the hybrid era. In fact, this model can become a vector of future studies within vital security in regional plane, allowing adding new levels and rearranging the structure of levels according to regional or nation-state specifics. The concrete concept and perception of national security and human security can be taken into account, as well as societal conditions, level of democracy, etc. Various cases of analysis based on this LEGO model can contribute to deeper understanding of human security and perspectives of this paradigm in today rapidly changing and turbulent world.

Furthermore, making human security the basis of international cooperation could respond to the current international debate on integrating the security and development agenda and the corresponding calls for a more coherent, effective and efficient international cooperation system.

Bibliographic references

Adger, W., de Campos, R., Siddiqui, T., Gavonel, M., Szaboova, L., Rocky, M., Bhuiyan, M., & Billah, T. (2021). Human security of urban migrant populations affected by length of residence and environmental hazards. Journal of Peace Research, 58(1), 50-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320973717

Ahmadzai, A. (2020). Local knowledge on development: The missing link in the research-policy nexus of sustainable development. Journal of Sustainable Development, 13(2), 132-147.

Alkire, S. (2003). A conceptual framework for human security. Working Paper. Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford.

Anam, S. (2018). Peacebuilding: The shift towards a hybrid peace approach. Jurnal Global & Strategis, 9(1), 37-48. https://doi.org/10.20473/jgs.9.1.2015.37-48

Asmussen, J. (2014). International crisis management and human security in the framework of 'hybrid wars' and unrecognised states. Security and Human Rights, 25(3), 287-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/18750230-02503001

Birch, M. (2024). Whatever happened to human security? Selective redefining by NATO after thirty years of backsliding. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 40(3), 215-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2024.2387958

Borch, O., & Heier, T. (2024). Preparing for hybrid threats to security: Collaborative preparedness and response. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781032617916

Chernysh, R., Chekhovska, M., Stoliarenko, O., Lisovska, O., & Lyseiuk, A. (2023). Ensuring information security of critical infrastructure objects as a component to guarantee Ukraine’s national security. Amazonia Investiga, 12(67), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2023.67.07.8

Dadwal, Sh. (2015). Non-traditional security challenges in Asia: Approaches and responses. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315090467

Daoudi, M. (2020, 14 December). Syria's human security is inseparable from its environmental health. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/syrias-human-security-inseparable-environmental-health/

DCAF (2024). Hybrid Security: Challenges and Opportunities for Security Sector Reform. https://acortar.link/M87CFM

Estrada-Tanck, D. (2016). Human security and human rights under international law: The protections offered to persons confronting structural vulnerability. Hart.

Fact. (2024, 23 May). The impact of war on the mental health of adults and children: analysis after more than two years of hostilities in Ukraine (part 1). https://acortar.link/fD2OYM

Gan, N. (2024). Climate change and threats to human security. Kalpaz Publications.

Gasper, D., & Gomez, O. (2015). Human security thinking in practice: 'personal security', 'citizen security' and comprehensive mappings. Contemporary Politics, 21(1), 1-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2014.993906

Gebre, G. (2015). Philosophical discourse on human security: Re-conceptualisation of the new security paradigm in Africa. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

Gilder, A. (2022). Human security. In O. Richmond & G. Visoka (Eds.), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Peace and Conflict Studies (pp. 494-503). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11795-5_191-1

Gradus Research Plus. (2024). Mental health and attitudes of Ukrainians towards psychological assistance during the war. https://acortar.link/UjprWM

Hanlon, R., & Christie, K. (2016). Freedom from fear, freedom from want: An introduction to human security. University of Toronto Press.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2023). Global Peace Index, 2023. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/GPI-2023-Web.pdf

Kaldor, M. (2006). Human Security: A Relevant Concept? Politique étrangère, 4, 1-16.

Khan, F., Muhabullah, M., Islam, R., & Khan, M. (2021). A cost-effective autonomous air defence system for national security. Security and Communication Network, 2021, 9984453. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2021/9984453

Khawas, V. (2014). Environmental challenges and issues of human security in Eastern Nepal. The Himalayan Miscellany, 25, 30-60.

Krause, K. (2013). Critical perspectives on human security. In M. Martin & T. Owen (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Human Security (pp. 76-93). Routledge.

Levchenko, A. (2023). Needs in the healthcare system are growing due to the war - Head of the WHO Office in Ukraine. Interfax-Ukraine. https://interfax.com.ua/news/interview/946050.html

MacGinty, R. (2010). Hybrid peace: The interaction between top-down and bottom-up peace. Security Dialogue, 41(4), 391-412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010610374312

Martin, M., & Owen, T. (Eds.). (2013). Routledge handbook of human security. Routledge.

McIntosh, M., & Hunter, A. (2017). New perspectives on human security. Routledge. ISBN 9781032923581

Middleton, J. (2023, July 4). Threats to human security rise in more than 20% of countries. Verisk Maplecroft. https://acortar.link/ZP5xo1

Muguruza, Ch. (2007). Human Security as a policy framework: Critics and challenges. Yearbook on Humanitarian Action and Human Rights, 4, 15-35.

Naidon, Y., Naumiuk, S., Rybynskyi, Y., Shemayeva, L., & Peliukh, O. (2024). Sanctions as a policy tool of Ukraine in countering threats to national security. Amazonia Investiga, 13(76), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2024.76.04.9

Paillé, P., Thue, K., & Heard, K. (2022). Human security and the 2022 NATO Strategic Concept: Knowledge, insights and lessons learnt. RAND Corporation.

Schütte, R., & Fordelone, T. (2006). Human Security: a paradigm contradicting the national interest? Carta Internacional, 1(2), 35-40.

Singh, J. (2016). Human security: A theoretical analysis. Prime Scholars Library, 4(3), 33-37. https://www.primescholarslibrary.org/articles/human-security-a-theoretical-analysis.pdf

Skulysh, Ye. (2023). Evolution of the concept of human security in international legal discourse. Scientific works of the Interregional Academy of Personnel Management. Legal Sciences, 2(62), 65-70. https://doi.org/10.32689/2522-4603.2022.2.10

Tadjbakhsh, Sh. (2005). Human security: Concepts and implications with an application to post-intervention challenges in Afghanistan. Les Etudes du CERI, 117-118, 1-77.

Toft, P. (2005). John J. Mearsheimer: An offensive realist between geopolitics and power. Journal of International Relations and Development, 8, 381-408. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800065

UN (2024, 27 February). As Syria's humanitarian crisis worsens, Security Council delegates stress need for Damascus to re-engage with constitutional committee. https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15602.doc.htm

UN Women (2022). Comparing military and human security spending: Key findings and methodological notes. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/Comparing-military-and-human-security-spending-en.pdf

UNDP (1994). Human Development Report 1994: New Dimensions of Human Security. Oxford University Press.

United Nations Development Programme (2022). New Threats to Human Security in the Anthropocene. https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210028332

Vejnović, D., & Obrenović, P. (2023). Human Security in Traditional Security Theories- Challenges and Perspectives. In Strategic Intersections: The New Architecture of International Security (pp.243-255). University of Belgrade. http://dx.doi.org/10.18485/isimod_strint.2023.ch15

Vision of Humanity. (2023). Conflict Trends in 2023: A Growing Threat to Global Peace. Retrieved from https://www.visionofhumanity.org/conflict-trends-in-2023-a-growing-threat-to-global-peace/

Walt, S., & Mearsheimer, J. (2006). The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy. KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP06-011, March.

https://amazoniainvestiga.info/ ISSN 2322- 6307

This article presents no conflicts of interest. This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Reproduction, distribution, and public communication of the work, as well as the creation of derivative works, are permitted provided that the original source is cited.