DOI: https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2024.81.09.18

How to Cite:

Alyeksyeyeva, I., Kaptiurova, O., & Orlova, V. (2024). The mask as a new means of communication: a multimodal analysis of its communicative value during the COVID-19 pandemic. Amazonia Investiga, 13(81), 234-248. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2024.81.09.18

The mask as a new means of communication: a multimodal analysis of its communicative value during the COVID-19 pandemic

Маска як засіб комунікаціх: мультимодальний аналіз її комунікативної значущості під час пандемії COVID-19

Received: August 2, 2024 Accepted: September 27, 2024

Written by:

Iryna Alyeksyeyeva

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3109-0331

WoS Researcher ID: GPG-2815-2022

Ph.D., in Linguistics, Associate Professor, Department of English Philology and Intercultural Communication, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine.

Olena Kaptiurova

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1051-8415

WoS Researcher ID: AAY-7828-2021

Ph.D., in Linguistics, Associate Professor, Department of English Philology and Intercultural Communication, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine.

Vira Orlova

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8025-8380

WoS Researcher ID: AAY-8117-2021

Ph.D., in Linguistics, Associate Professor, Department of English Philology and Intercultural Communication, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine.

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2022) transformed the face mask from a medical device into a communicative tool. This study analyses the multimodal nature of community masks in the United States, demonstrating how their design elements convey political, social, and personal messages. Through a semiotic analysis of mask images, the research reveals the use of colors, patterns, slogans, and wordplay to express political affiliation (e.g., pro-Trump, pro-Biden), social stance (e.g., Black Lives Matter, vaccination status), and individual identity (e.g., mood, fashion). The findings highlight the mask's evolution into a platform for public expression, comparable to profile pictures and slogans on social media, contributing to our understanding of communication in the digital age. The study also underscores the interdiscursive nature of mask-wearing practices, intersecting with discourses on identity, politics, and public health.

Keywords: mask, multimodality, message, verbal and nonverbal communication, communicative value.

Анотація

Протягом пандемії COVID-19 (2020–2022) захисна маска перетворилася з медичного предмета на засіб комунікації. У дослідженні подано аналіз мультимодальної природи тканинної маски в Сполучених Штатах Америки, який свідчить про те, що елементи дизайну цього аксесуара передають політичні, соціальні та особисті повідомлення. Семіотичний аналіз масок виявив те, як кольори, малюнки, слогани та мовна гра використовуються задля вираження політичних вподобань (наприклад, прихильності до Трампа чи Байдена), позиції щодо соціальних проблем (наприклад, підтримка Black Lives Matter, вакцинація) та особистої ідентичності (наприклад, настрій, дотримання модних трендів). Результати дослідження свідчать про еволюційну транформацію маски у платформу для публічного самовираження, схожу на візуальні елементи профілів чи слогани у соціальних мережах, що доповнює розуміння комунікації у цифровому світі. Дослідження також виявляє інтердискурсивну природу практик носіння маски, які перетинаються з дискурсами ідентичності, політики та громадського здоров’я.

Ключові слова: маска, мультимодальність, повідомлення, вербальна та невербальна комунікація, комунікативна значущість.

Introduction

From 2020 to early 2022, the coronavirus pandemic kept the world under siege and interfered with all aspects of social life: education, economy, social life, etc. The policies adopted to curb the virus varied in their severity at different stages but most countries had to go through the stages of distancing, restrictions on travelling and even lockdowns. Despite differences in the measures taken to prevent the virus from spreading, the common feature of any public place was face masks, which sparked fierce reactions and brought to the surface cultural significance attributed to the human face, human life, human rights and freedom (Klepikova et al., 2021; Pevko et al., 2022). The introduction of this tiny piece of cloth as a compulsory accessory turned the piece into “a potent symbol of our changed reality” (Wong, 2021). Overall, alongside the coronavirus image and the flatten-the-curve graph, the face mask became iconic of the pandemic as much as generic, i.e., these three were adapted to numerous contexts of the crisis as visuals in their own right (Aiello et al., 2022, p. 313–314).

Though the mask started as a standardized medical item imposed almost globally, the seeming uniformity of mask-wearing was gradually undermined locally since mask-wearing appeared to be deeply connected to social and cultural practices (Martinelli et al., 2021, p. 1) and raised a few sociocultural, ethical and political issues because dress is “a situated bodily practice which is embedded with the social world and fundamental to micro-social level” (Entwistle, 2000, p. 66).

There appeared a trend to turn masks into fashion items or/and a surface to make a statement of various types, namely a fashion statement, a political statement or an identity claim. In fact, since there was no way to avoid face-covering, one could not help communicating one’s attitude to the anti-corona policies, once one went out: the message was sent either by the choice of one’s mask design or by the manner of wearing it.

The impact of the pandemic has been multifaceted and long-lasting. Experts estimate its effect on the USA gross domestic product as “twice the size of that of the Great Recession of 2007–2009”, “20 times greater than the economic costs of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and 40 times greater than the toll of any other disaster to befall the U.S. in the 21st century” (Hlávka & Rose, 2023). The pandemic has brought up issues of mental health treatment and vaccination as well as introduced new behavioural patterns (UAB News, 2022); the detrimental effect on the mortality, fertility rates and new migration policies of 2020-2022 will still be felt in 2026 (Tilstra et.al., 2024); the new social reality has aggravated social inequality issues in the USA (Hu, 2022). There is ongoing research into social, psychological and cultural aspects of the pandemic (see, for example, (Aiello et al., 2022; Frosh & Georgiou, 2022; Manalastas, 2023)).

The article aims to analyse the transformation undergone by the surgical mask during the pandemic. The sections of the article are designed to answer the following questions:

Hence, the research explores how, in the US context, the mask started as a protective object and ended up as a means of expressing the wearer’s stance on issues of social, economic, political and personal nature.

Literature review

The analysis of the medical mask as a communicative means during the pandemic requires a brief overview of the history of and attitudes to face covering.

In the Middle Ages and later on, masks were worn by Europeans (mostly women) during pilgrimages and carnivals. At that time, the purpose of face-covering was to protect women from an evil eye and the sun or to hide the mask-wearer’s identity (Phillips, 2022). The medical mask appeared in China during the 1910–1911 plague epidemic and came to the USA as obligatory protective equipment for medical workers at the time of the 1918 Spanish flu. Compulsory mask-wearing caused a wave of noncompliance among Americans who defied masks as an unconstitutional infringement of civil liberties (Navarro, 2020).

The recent studies into face-covering often adopt the comparative approach and focus on cultural hybridity. (Shirazi, 2003) is one of the first remarkable analyses offering an insight into the multiplicity of meanings and communicative effects of the veil in different discourses ranging from Persian poetry to American and Saudi advertising to Iranian and Indian films and government-funded posters. The veil is perceived differently in various cultural contexts and historical epochs. A similar research, though into the item of clothes, shalwar, was conducted in 2022 and revealed a similar multiplicity of its interpretation: the shalwar was perceived as a symbol of progressive gender neutrality in the West and as an epitome of traditionalism in the East (Celikkol, 2022).

A valuable observation is made by Jardim who notes that clothes play the critical role in “defining social interactions” (Jardim, 2019, p. 72). Jardim examines the corset in the West and the veil in Muslim cultures to argue that these clothes erase the marks of the subject and help enter social interactions as social roles rather than individuals (Jardim, 2019, p. 69). Thus, clothes “become a major social actor” (Jardim, 2019, p. 72) instrumental for “the complete con-formation to the rules and conventions of society, or its destruction” (Jardim, 2019, p. 72).

Mask-wearing during the 2020 pandemic encourages Jardim to compare semiotics of the niqab and the surgical mask. She notes that “the covering of the face is the rawest form of denying individual subjectivity and installing a (collective) role which, in its turn, is constructed around specific positions in the situation of communication” (Jardim, 2020, p. 169). Hence, the niqab marks the feminine role and corresponds to one narrative. The functions of the surgical mask are twofold: it both correlates a surgeon with the medical profession and sacralizes the surgeon’s figure. However, when worn by a civilian during the pandemic, “the mask installs the role of cooperator with the maintenance of social order and collective health” (Jardim, 2020, p. 169). The narrative of civilian mask-wearers is that of compliance with the order to curb the virus. Moreover, the mask becomes an object that “promotes the preservation of the totality, the collective social organism of a Nation” (Jardim, 2020, p. 173), while the niqab helps maintain a social organism of the Ummah (Jardim, 2021, p. 173). Jardim concludes that the religious and the medical items produce similar thematic roles of the ‘complying citizen’ or the ‘believer’: they aim at preserving the social order. According to Jardim, “[t]he only difference seems to be the addresser one fears: the Government or God” (Jardim, 2021, p. 175).

Leone is among the first who published a comparative analysis of the interpretations given to the surgical mask in the East and the West. He also looks into how these meanings play out in different cultural contexts during the coronavirus pandemic. In (Leone, 2020), he puts forward the assumption of the “progressive ‘semiotisation’ of the medical face mask” that results in “the creation of local cultures, in which this facial medical device interacts with pre-existing cultures of the face and of the mask” (Leone, 2020, p. 47). While writing his article in 2020, Leone pointed out the “traumatic medicalization of the face” (Leone, 2020, p. 56) and insisted on the urgency of “a new semiotics of the medical face mask” (Leone, 2020, p. 57).

Leone grasps the inherent peculiarities of the medical mask and its paradoxical usages of that moment. In particular, he points out that the mask differs from, for example, a hat or a pair of sunglasses, in that it is not worn “for purposes of signification and communication” (Leone, 2020, p. 58). According to (Leone, 2020), for a Westerner, the denotation of the medical mask is a protective object, while its connotation is “inseparable from an idea of emergency, risk, and danger” (p. 58). Yet, the pandemic made the meaning of mask-wearing ambiguous: it became obscure who the mask protected – the mask-wearer or the people around or, as (Martinelli et al., 2021) put it, the pandemic brought about “a collapse between the status of being at risk and being a risk” (Martinelli et al., 2021, p. 613). In 2020, people wearing masks were seen as cautious and those who broke the rule presented a potential danger (Leone, 2020, p. 59–60).

Alongside the uniformity of the mask, studies argue for the connection between the mask and identity expression. (Martinelli et al., 2021) applied qualitative descriptive analysis to frame “the four dimensions of the societal and personal practices of wearing (or not wearing) face masks: individual perceptions of infection risk, personal interpretations of responsibility and solidarity, cultural traditions and religious imprinting, and the need of expressing identity” (Martinelli et al., 2021, p. 606).

Interestingly, whereas in China, for example, mask-wearing was “mostly a public health issue rather than a political issue” and the mask became a moral symbol that “reduces wearers’ deviant behaviour by heightening their moral awareness” (Lu et al., 2022, p.1), the mask turned into a means of social positioning tightly bound with politics in the USA. In particular, examining the US discourse of powerful anti-masking movement that coincided with the 2020 presidential election, where the candidates, Joe Biden and Donald Trump, held the opposite views on COVID-related restrictive measures, Kahn distinguishes three metaphors used by US anti-maskers. The metaphor ‘Mask wearers are sheep’ suggests that mask-wearers obediently follow the herd and ‘are easily fleeced’. The metaphor also brings up the images of ‘wolves’ and ‘shepherds’ (Kahn, 2022, 2397). The metaphor ‘Masks are COVID-burqas’ draws on the idea of otherness and relates the surgical mask to burqa seen as a symbol of oppression and submission. The third metaphor, ‘Masks are an unfree act’, presents the mask as an item that strips people of their identity and is “incompatible to a democratic society” (Kahn, 2022, 2403).

The previous research has not yet targeted closely the communicative value of the mask in the years 2020–2022, so this study is relevant as it is aimed at exploring the mask from the perspective of the messages sent by its design.

Methodology

The research is a qualitative study that draws on Barthes’ idea of semiology of clothing as syntactic rather than lexical: the meaning of clothes comes not from items as such but rather from their functions and oppositions (Barthes, 2013, p. 28). In other words, just like a syntactical unit in a language acquires its meaning in a sentence, the meaning of the mask in 2020–2022 is contextualized and its communicative value may be understood only within its social and cultural environment. Thus, the standard semiotic method helps to explore the meanings expressed in the mask and embedded in broader social contexts.

The methodology of the study employs multimodal analysis developed by Kress & Van Leeuwen (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 1996; Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2001) that provides the tools to research multiple codes used in human communication (e.g., memes (How, 2022) and TikTokers’ posts (Popivniak et al., 2022). In this research, the multimodal approach was applied to examine the contribution of verbal and visual means to the message conveyed by masks during the coronavirus pandemic.

The first stage of the research aimed at clarifying the nomenclature of face coverings and their nominations so as to identify the place of the medical mask among face-covering accessories. To achieve this objective, the study examined dictionary definitions, encyclopedias and reference sources such as the sites of the World Health Organization, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency, etc.

The second stage consisted of continuously collecting mask images from photos in English-language mass media online publications as well as from advertisements of masks offered for sale by online shops that emerged online in 2020–2022. The sampling yielded 83 images (21 photos accompanying mass media articles and 62 online shop advertisements).

The third stage involved employing multimodal analysis tools: the mask was approached as a multimodal text that performs ideational, textual and interpersonal metafunctions. Accordingly, the research viewed mask elements as units selected to represent ideas, arranged coherently and used to produce an effect on others. Thus, the communicative value of any mask was seen as an aggregate of its verbals and nonverbals and tightly bound to the political and social context of 2020–2022.

The approach and the design of the research entail certain limitations. First of all, employing the qualitative method presupposes the researcher’s subjectivity and, therefore, the possibility of other interpretations. Second, the size of the sample and the lack of information about the actual popularity of certain mask designs may be seen as a deficiency of the research.

Results and Discussion

‘Medical mask’ in the nomenclature of face covering

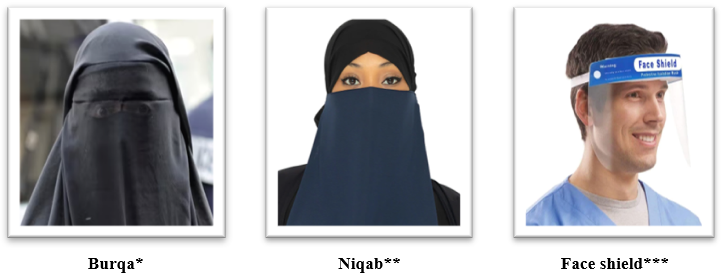

The umbrella term ‘face covering’ that denotes the ‘veil’ and tends to be associated nowadays with an accessory worn by women to cover their head and shoulders in Eastern countries (“Veil”, Merriam-Webster, n. d. d) is the main nomination referring to a piece of cloth used to cover the lower part of the face. Its variants are ‘burqa’ and ‘niqab’. Another type of ‘face covering’ is ‘face shield’ usually made of clear plastic (“Face shield”, Merriam-Webster, n. d. c) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Face covering: burqa, niqab, face shield.

Source: (Fluentes, 2014); * (Al Shams Abayas, n.d.); *** (Amazon, n.d., c)

Approached from this perspective, ‘mask’ is yet another type of ‘face covering’ along with veil and face shield. The lexeme ‘mask’ denotes a wide range of objects that are essentially a piece of cloth with a variety of functions. Besides the first meaning, i.e., “a protective covering for the face or part of the face” (“Face mask”, Merriam-Webster, n. d., a), Merriam-Webster Dictionary offers other definitions: “a cover or a partial cover of the face used for disguise”, “a figure of a face worn on the stage in antiquity to identify the character and project the voice”, “a grotesque false face worn at carnivals or in rituals”, etc. (“Mask”, Merriam-Webster, n. d., b). Thus, masks are categorised into protective, ritual, festive and theatrical.

Subtleties of ‘protective mask’ came to the fore in 2020. In their entries, dictionaries are careful to highlight the nuances of ‘mask’, ‘non-medical face mask (community mask)’ and ‘medical face mask (surgical or procedural mask)’. In particular, ‘protective mask’, also known as ‘non-medical face mask’ or ‘community mask’, refers to “various forms of self-made and commercially available masks, including re-usable face covers made of cloth, other textiles and other disposable materials” (EASA, n. d.). These masks do not adhere to any standards and may not be used in hospitals by healthcare professionals.

The ‘medical face mask (surgical or procedural mask)’ denotes an object that meets definite standards:

a medical face mask (also known as a surgical or procedural mask) is a medical device covering the mouth, nose and chin ensuring a barrier that limits the transition of an infective agent between the hospital staff and the patient. They are used to prevent large respiratory droplets and splashes from reaching the mouth and the nose of the wearer and help reduce and/or control at the source the spread of large respiratory droplets from the person wearing the face mask. Medical masks comply with the requirements defined in European Standard EN 14683:2019+AC2019 (EASA, n. d.).

Our research focuses primarily on the communicative value of the ‘protective mask’, i.e., the study considers messages conveyed by ‘community masks’ and ‘medical masks’: both of them were acceptable due to the dire shortage of medical masks at the beginning of the pandemic even for frontline workers (medical staff) (World Health Organization, 2020), which made governments compromise the rigidity of the standard requirements and turned community masks into the most common protective item. In the northern Italian region of Lombardy, for example, the authorities enforced the legal obligation for everyone to wear a mask in public places and allowed to wear scarves to cover one’s nose and mouth instead of medical masks (Leone, 2020, p. 61). As a result, people had to resort to ‘community masks’, self-made or improvised masks (for example, ‘face scarves’ (see Figure 2):

Figure 2. Face covering scarf.

Communicative value of the mask in politically charged settings

The mask as identity disguise

“The face is a fundamental interface of human interaction” (Leone, 2020, p. 65), and it is the face that tops the list of other biometrics along with fingerprints, retina, voice, etc. (Gillis, 2021). It is not surprising that medical masks have often been used in civil marches, demonstrations and protests whose participants wanted to remain unidentified. This is what happened in Kyiv, Ukraine, in December, 2013, in Hong Kong in June, 2019, all over the United States during the 2020 BLM demonstrations, in the US Capitol in January, 2021, or in Bogota, Colombia, in May, 2021 (see Figure 3). Moreover, the bans on wearing face covering imposed by the Ukrainian government in 2014 and by the Hong Kong government in 2019 immediately brought masked protesters into the streets. The people defied the governments’ intention to limit the ability to expose or conceal their faces (and, consequently, identities).

Figure 3. Masked protesters in Chicago, USA (Nam, 2020), and Bogota, Colombia (Agarita, 2021)

Figure 3. Masked protesters in Chicago, USA (Nam, 2020), and Bogota, Colombia (Agarita, 2021)

The community mask as a statement of political affiliation

At the beginning of the pandemic, when mask-wearing was made obligatory and medical masks were scarce, mask-manufacturing companies sprang up and started offering community masks of various designs. Since the target consumer was literally everybody, the manufacturers tried to adjust them to proponents of various social trends popular at that moment. Hence, the plain surface of the mask was modified by adding a variety of nonverbal and verbal elements. As a result, community masks preserved their protective function and simultaneously turned into space for political statements.

May 2020 was marked not only by the gradual removal of the lockdown restrictions but also by the rise of the BLM movement, which immediately found its way onto the community mask surface. Figure 4 contains the masks that inform of the wearers’ support to the BLM movement. Here, the nonverbals are the colours (black and white), the raised up clenched fist and, on one mask, the flag of the USA that localizes the protester. The verbals are the slogan “BLACK LIVES MATTER” and “I CAN’T BREATHE”, the last words of George Floyd whose murder set off the protests. The “I can’t breathe” mask is creative because it features the clenched fist instead of the pronoun ‘I’.

Figure 4. Community masks with BLM-related slogans (Saris & Things, n.d.)

Another milestone of 2020 and early 2021 was the presidential race in the USA. Mask surfaces started displaying Americans’ voting preferences and, therefore, their communicative value became that of an electioneering tool. Interestingly, there is an overwhelming disproportion between pro-Trump and pro-Biden masks, with the former outnumbering the latter by a 3 to 1 ratio.

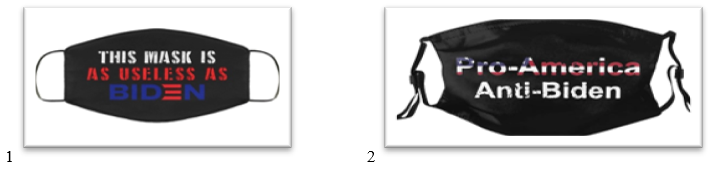

Pro-Trump masks may be divided into two groups: one group is pro-Trump proper and the other is explicitly anti-Biden.

Figure 5 features the masks of the ‘pro-Trump proper’ type. On masks 1 and 2, one finds the pivotal slogan “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN” (or its MAGA abbreviation), based on the assonance of /eɪ/. The slogan of mask 3, “Jesus is my savior. Trump is my president”, draws on syntactic parallelism (S + link verb + Predicative): Trump’s core supporters (conservative Christians) recognize no other saviour but Jesus and, similarly, they do not see any alternative to Trump as the president. The slogan “I STAND WITH TRUMP” on mask 4 is a straightforward statement of political preferences. The masks are multimodal: their verbals are supported by meaningful choices of the colour (red is the colour of the US Republican party (masks 1 and 2)), the image of the US flag, and the heart that stands for U in ‘Trump’ and the pattern of the US flag, respectively.

Figure 5. Pro-Trump community masks (1 (Etsy, n.d., a); 2 (CapWholesalers, n.d.); 3 (myutopia, n.d.); 4 (Amazon, n.d., a)

The second group of masks designed for Trumpists is not straightforwardly pro-Trump but is blatantly anti-Biden. In Figure 6, for example, the slogan “This mask is as useless as Joe Biden” on mask 1 claims that mask-wearing policies supported by Biden and criticized by Trump are just as ineffective as the Democrats’ leader himself. The verbals on mask 2 imply the equivalence between being pro-American and being anti-Biden. The idea of equivalence is boosted by the structural (i.e., semi-suffix + proper noun) similarity of the words Pro-America and Anti-Biden. The verbal messages of the masks are complemented with the nonverbal elements: the patriotic Pro-America component features the colours of the American flag (the blue background, the white first two lines, the red third line), stars and stripes, which contrasts with the white monochromic letters of the Anti-Biden word; the similarity of the hyphenated spelling of the two words suggests that they are synonyms.

Figure 6. Anti-Biden pro-Trump community masks (1 (Etsy, n.d., b); 2 (Amazon, n.d., b)

As it has been mentioned, explicitly pro-Biden masks are few. The reason for the scarcity may be the fact that pro-Biden messages were sent by the masks propagating Biden’s policies (e.g., mask-wearing, vaccination, revisionism of colonization and interracial relations promoted by the BLM movement). The sample contains only one mask that sends an implicit anti-Trump and, therefore, pro-Biden message (see Figure 7), “Make Politics Boring Again”. The mask is red and white, there are no remarkable nonverbals but the text itself is memorable because it alludes to Trump’s “Make America Great Again” as well as to Trump’s bright and outspoken performance both as a showman and a politician.

Figure 7. Pro-Biden community mask (Redbubble, n.d., c)

The community mask as an instrument of social positioning

Social life during the Covid-19 pandemic was determined by the two policies: lockdown and obligatory vaccination.

The key slogan of early 2020 was “Stay home, stay safe”, the motto of the lockdown (Figure 8). On the surface, it is only logical that this catchphrase appeared on the mask that became iconic, yet, one can’t help noticing the paradoxical controversy of its purpose and slogan: one puts on the ‘stay-home’ mask right at the moment of leaving home.

Figure 8. Community mask with ‘STAY HOME’ slogan (Needen, n.d.)

Alongside the presidential election, the landmark of the second half of 2020 and the entire 2021 was the vaccination issue. Though there appeared several vaccines (Pfizer, Moderna, CoronaVac and AstraZeneca), it was the Pfizer vaccine that gained the status of the ‘elite’ one. People sought a Pfizer, bloggers boasted their Pfizer jabs and mocked the losers who had to do with anything but a Pfizer (Popivniak et al., 2022).

Masks provided people with an extra space to position themselves as vaccinated or unvaccinated. Interestingly, compared to other vaccines, Pfizer masks are more numerous and creative. Hence, one may argue that community mask producers reacted to the vaccination trend and made masks that helped their owners inform that they had been vaccinated. They could choose to be more specific and enhance their image by claiming access to the elite vaccine.

Figure 9 displays masks with neologisms coined during the pandemic. Obviously, the noun Pfizer, originally the name of a pharmaceutical company, was turned into a common noun to refer to a vaccine through a metonymic transfer in I took PFIZER (mask 1) and was further converted to the verb to Pfizer in I’ve been PFIZERED (mask 2). The consonant cluster PF uncommon for the English language evokes associations with the glamourous vaccine. This phonetic feature is used in the playful I PFEEL PFINE (mask 1). To draw attention to the similarity, the graphically highlighted words on the mask are those that start with PF. Two of the three masks in Figure 9 contain the image of a syringe, which makes it clear that out of the whole range of Pfizer’s products, it is the vaccine that is meant.

Figure 9. Pfizer-based community mask (1 (Redbubble, n.d., f); 2 (Redbubble, n.d., b); 3 (Redbubble, n.d., e)

Figure 9. Pfizer-based community mask (1 (Redbubble, n.d., f); 2 (Redbubble, n.d., b); 3 (Redbubble, n.d., e)

Paradoxically, community masks were also used by anti-maskers to protest against mask-wearing, expressing the protest by verbalizing the ‘sheep’ metaphor on mask surfaces. Mask (1) in Figure 10 is multimodal: the sheep with the US-flag pattern specifies the location, the image of the animal combined with the text The nation of sheep will beget a government of wolves implies that people’s obedient compliance with the masking policies will entail tyranny of authorities. Mask (2) is no less metaphorical. It does not name submissive mask-wearers ‘sheep’ but it features an image of a sheep and the verb obey suggesting that those who wear masks are obedient sheep.

Figure 10. Ani-mask community masks, 1 (Redbubble, n.d., a); 2 (Redbubble, n.d., d)

Figure 10. Ani-mask community masks, 1 (Redbubble, n.d., a); 2 (Redbubble, n.d., d)

Another communicative value of the mask was the statement of prestige. Since masks became mandatory, fashionable clothes brands began including this accessory in their ensembles. The status claim was made by the logo of, for example, Louis Vuitton or Chanel (see Figure 11) that informed of their wearers’ social status and purchasing power.

Figure 11. Louis Vuitton (eBay, n.d.) and Chanel (Rose, 2020) community mask.

Figure 11. Louis Vuitton (eBay, n.d.) and Chanel (Rose, 2020) community mask.

The community mask as a means of personality expression

Along with providing surfaces for statements of political and social positioning, community masks could be designed and marketed as markers of their wearer’s psychological state or self-perception. The connection between a personality type (or mood) and the pattern and colours of the mask was determined by the mask manufacturer that classified them as such with verbal labels. Figure 12 displays personality-based masks without any verbal components that are marketed under the lables of “creative”, “dramatic”, “romantic”, etc. (Davis, 2020). The marketing labels rely entirely on the stereotypes of visual (colours and patterns) representation of ‘creativity’ (abstract patterns and bright colours), ‘dramatism’ (black and white geometry with sharp angles), ‘romanticism’ (flowery pattern), ‘classicism’ (black and white polka dots) and ‘chic’ (the monochrome beige).

Figure 12. Personality-and mood-based community masks (Davis, 2020).

The masks functioned to specify the wearer’s personality type and/or mood. Presumably, the choice of a mask was influenced not only by one’s intuitive preferences for colours and patterns, but also by the producer’s verbal labels accompanying each item.

Thus, the trajectory the protective mask made during the pandemic when it started as the rigidly standardized medical mask and ended up with a wide range of community masks shows how what set out as a homogeneous part of a professional uniform was modified, personalized and appropriated as soon as this item became a compulsory accessory of everybody’s outdoor outfit.

The semiotics of the mask should be viewed ‘syntactically’ rather than ‘lexically’. In other words, the mask is not a ‘lexeme’ but a ‘syntagm’ whose meaning is the sum of its verbal and nonverbal elements. As Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996) argue, “not everything that can be realized in language can also be realized by means of images, or vice versa” (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 1996, p. 17). In the case of protective masks, nonverbals (colours, patterns and images) make the message ‘set the tune’ (for example, determine political affiliation, attitude or ‘mood’), whereas the verbals are elements that make the message more specific and add rhetorical sophistication.

The study into the mask during the pandemic brings up the issue of interdiscursivity and supports the statement that “discourses are linked to each other in various ways” (Reisigl & Wodak, 2017, p. 90): the mask-wearing practices overlap with discourses on fashion, on freedom and human rights, on social responsibility, on cultural, religious, professional and personal identity, etc. Making sense of different attitudes to mask-wearing in different social groups and geographical areas is impossible without considering historical and cultural peculiarities of these groups. Since the face is an important semiotic component of human communication, the ways the face is handled during interactions vary across cultural and political systems. Any new accessory or practice that modifies the face gets immediately noticed and assessed triggering instinctive reactions. The mask as a mandatory item sparked fierce debate and resistance in the West because it undermined the conventions of Western society, which was aggravated by the perceived opposition to the Islamic tradition.

Communicative functions of the mask that evolved from a medical item into a meaningful element that informed of its wearer’s ideology, political preferences, social status, personality and, in a way, even lifted the confidentiality of one’s health record make it comparable to profile pictures on social media or accompanying slogans on Instagram and Telegram. One may also argue that masks turned into another element of linguistic landscapes and were used as space to transmit political or personal messages.

The findings of the research are by no means exhaustive due to the qualitative method where researchers’ interpretations inevitably impact the study. This research attempted to overcome this limitation through co-authorship, where the co-authors tried to be aware of their subjectivity and to neutralise each other’s bias. The limitation related to the sample, its size and lack of detailed information about the popularity of the mask designs in the United States in general and certain states (or cities, towns) in particular may be seen as potential issues for further investigation. However, street photographs in the sample may be seen as evidence of widely worn designs. On the other hand, it is impossible to clarify the demand for masks offered by e-shops, though some of the items were marked as sold out in early 2023, which may substantiate the assumption that the sample represents the mainstream trends in 2020–2022.

Conclusions

Introducing compulsory mask-wearing during the coronavirus pandemic brought about the transformation of both the protective mask and its function in everyday discourse. Initially, the meaning of the protective mask was primarily the medical mask that was an accessory of health care workers and, at times, their patients. Correspondingly, the medical mask was ‘scientific’, standardized and discursively unambiguous. As medical masks were scarce at the beginning of the pandemic, its substitute, the community mask, with all its variety, became an obligatory everyday item worn by everyone outside their home.

The semiotic analysis of the community masks worn during the coronavirus pandemic uncovers their communicative value provided by the multimodality of their design. In 2020-2022, the mask turned into the surface used to make public statements on the wearer’s political, social and personal positioning.

Verbal and nonverbal elements of the masks convey meanings that form a ‘syntagm’ and shape the final message. The nonverbals such as colours, patterns, images tend to appeal to shared background knowledge (the colours and the pattern of the US flag evoke the idea of national belonging, the red colour refers to the Republican party, a syringe is a metonymy for medicine and vaccination, the flowery pattern stands for romantic mood, etc.).

The verbal elements in their turn make the message more specific, contextualize it, incorporate it into the current political and social discourse. The verbal components of the community masks contain syntactic parallelisms, metaphors, allusions, neologisms and word play, which attracts attention and makes the messages memorable.

This research is woven into modern communication studies. On the whole, the ‘mask case’ highlights the overwhelming trend towards multimodal interactions in the 21st century. In particular, it demonstrates that when the individuality of the face was replaced by the uniformity of the mask, it was mask surfaces that people started using to inform of their personal, social and political identity. In addition, the sample reveals the impact of digital communication on face-to-face interactions, namely the similarity between masks and social media profiles. Another important conclusion the research suggests is that, used to take a stand on political and social issues, the mask was conducive to developing participatory culture.

The current research may be furthered by a comparative study of mask-wearing practices and attitudes towards the mask in different cultures during the pandemic. Another potential field of study may be the evolution of the mask after the pandemic. Presumably, it has transformed into neck gaiters (or neck warmers) worn by activists to send political messages during the ongoing 2024 presidential race in the USA.

Bibliographic References

Agarita, N. (2021). Colombian demonstrators take to the streets in anti-government protests demanding the end to police violence and greater economic support as COVID-19 rages [Photograph]. Aljazeera. Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/5/12/colombia-enters-third-week-of-anti-government-protests

Aiello, G., Kennedy, H., Anderson, C. W., & Mørk Røstvik, C. (2022). ‘Generic visuals’ of Covid-19 in the news: Invoking banal belonging through symbolic reiteration. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(3 – 4), 309-330. http://doi.org/10.1177/13678779211061415

Al Shams Abayas. (n.d.). Beda Half Niqab Navy 2. [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.shamswear.com/cdn/shop/products/BedaHalfNiqabNavy2_700x.jpg?v=1635348760

Amazon (n.d., a). Rqwaaed I Stand With Trump Face Mask Adjustable Breathable Balaclava With Filter [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.amazon.com/Rqwaaed-Adjustable-Breathable-Balaclava-Filter/dp/B0D7Q4L56V

Amazon (n.d., b). Pro America Anti Biden Face Mask with 2 Filter Adjustable Breathable Reusable Dust Mask [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.amazon.com/America-Filter-Adjustable-Breathable-Reusable/dp/B09VFMM7NG

Amazon (n.d., c). 10pcs Safety Face Shield with Clear Adjustable Protective Visor Film, Anti-Saliva/Anti-Spitting Splash/Anti-Fog Facial Cover for Women Men, Resistant to External Intrusion. [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.amazon.com/Adjustable-Protective-Anti-Saliva-Anti-Spitting-Resistant/dp/B086GVP8DP

Barthes, R. (2013). The Language of Fashion. Sydney: Bloomsbury.

CapWholesalers. (n.d.). Pre-Decorated MAGA Mask [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.capwholesalers.com/pre-decorated-maga-mask-ships-approx-7-14-days

Celikkol, Y. (2022). Progressive in the West, backward in the East. Shalwar’s trials with modernity. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(5), 518-535. https://doi.org/10.1177/13678779221094058

Davis, N. (2020). Facing Up To Face Masks. MyPersonalStyle. Retrieved from https://mypersonalstyle.co.uk/facing-up-to-face-masks

EASA. (n.d.). What is meant by a “medical face mask”? Retrieved from: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/faq/115286

eBay. (n.d.). NEW LOUIS VUITTON Monogram Brown Knit Face Mask S00 M76747 [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.ebay.com/itm/186690614750

Entwistle, J. (2000). The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Etsy (n.d., a). Make America Great Again Mask Three Layer Cotton Reusable Washable Maga Face Mask Free Shipping within USA Trump 2020 Mask [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.etsy.com/listing/846841875/make-america-great-again-mask-three

Etsy (n.d., b). Useless Biden Face Mask - Sarcastic President Face Cover Trump Supporter [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.etsy.com/listing/984330841/useless-biden-face-mask-sarcastic

Fluentes, G. (2014). A woman wearing a burqa [Photograph]. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/01/france-burqa-ban-upheld-human-rights-court

Fridaze. (n.d.). Silks by Fridaze Premium Face Masks Scarf – Coral Blocks [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://www.shopfridaze.com/products/silks-by-fridaze-premium-face-masks-scarf-orange-blocks

Frosh, P., & Georgiou, M. (2022). Covid-19: The cultural constructions of a global crisis. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(3–4), 233-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/13678779221095106

Gillis, A.S. (2021). Biometrics. TechTarget. Retrieved from: https://www.techtarget.com/searchsecurity/definition/biometrics

Hlávka, J., & Rose, A. (2023). COVID-19’s Total Cost to the U.S. Economy Will Reach $14 Trillion by End of 2023. USC Schaeffer. Retrieved from: https://acortar.link/VuofTs

How, C. (2022). What do they Really “Meme”? A Multimodal Study on ‘Siakap Langkawi’ Memes as Tools for Humour and Marketing. 3 L: Language, Linguistics, Literature, The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 28(2), 160-180. https://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2022-2802-11

Hu, E. (2022). How COVID-19 Has Magnified Pre-existing Inequalities in the US. Global Development Policy Center. Retrieved from: https://acortar.link/xiiwic

Jardim, M. (2019). The corset and the veil as disruptive manifestations of clothing: the tightlacer and the Tuareg. dObra[s] 11(25), 54-74.

Jardim, M. (2020). The Corset and the Hijab Absence and Presence in the 19th- and 20th-century Fashion System. Actes Sémiotiques, 123, 1-20, Available at: https://research.uca.ac.uk/5439/

Jardim, M. (2021). On Niqabs and Surgical Masks: a Trajectory of Covered Faces. Lexia. Semiotics Journal, 37–38, 165-177. http://doi.org/10.4399/97888255385338

Kahn, R. (2022). COVID Masks as Semiotic Expressions of Hate. International Journal of the Semiotics of Law, 35, 2391-2407. DOI: 10.1007/s11196-022-09885-7

Klepikova, O., Kachuriner, V., Makoda, V., Kryvosheyina, I., & Popeliuk, V. (2021). Protection of public interests by narrowing private interests: where is the limit? Amazonia Investiga, 10(38), 148-157. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2021.38.02.14

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Arnold Publishers.

Leone, M. (2020). The Semiotics of the Medical Face Mask: East and West. Signs & Media, 1, 40-70. http://doi.org/10.1163/25900323-12340004

Lu, J.G., Song, L.L., Zheng, Y., & Wang, L.C. (2022). Masks as a moral symbol: Masks reduce wearers’ deviant behavior in China during COVID-19. PANS 119(41), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2211144119

Manalastas, N. E. L. (2023). (De-)Monstering COVID-19: a diachronic study of COVID-19 virus multimodal metaphors in Philippine editorial cartoons, 2019–2022. Multimodal Communication, 12(3), 207-222. http://doi.org/10.1515/mc-2023-0015

Martinelli, L., Kopilaš, V., Vidmar, M., Heavin, C., Machado, H., Todorović, Z., Buzas, N., Pot, M., Prainsack, B., & Gajović, S. (2021). Face Masks During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Simple Protection Tool with Many Meanings. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 606-635. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.606635

Merriam-Webster. (n.d., a). Face mask. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/face%20mask

Merriam-Webster. (n.d., b). Mask. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mask

Merriam-Webster. (n.d., c). Face shield. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/face%20shield

Merriam-Webster. (n.d., d). Veil. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/veil

Myutopia. (n.d.). Jesus is my Savior - Trump Is My President Fitted Face Mask w. Adjustable Ear Loops [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.myutopiashoutout.com/products/jesus-is-my-savior-trump-is-my-president-fitted-face-mask-w-adjustable-ear-loops

Nam, Y. H. (2020). Protesters in Chicago on Saturday [Photograph]. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from: https://acortar.link/G7kQ1w

Navarro, J. A. (2020). Mask Resistance During a Pandemic Isn’t New – in 1918 Many Americans Were ‘Slackers’. The Conversation. Available at: https://acortar.link/PPKiDu

Needen. (n.d.). Stay Home Mask [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.needen.cz/blank-apparel-accessories-c37029/masks-s41906

Pevko, S., Romaniuk, V., Perekopskyi, S., Khan, O., & Shaituro, O. (2022). Legality of restrictions on human rights and freedoms in a Covid-19 Pandemic: The experience of Ukraine. Amazonia Investiga, 11(53), 122-131. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2022.53.05.12

Phillips, B. (2022). In 1500s Europe, masks were fashionable – and scandalous. National Geographic. Available at: https://acortar.link/1gq6se

Popivniak, O., Torosian, O., & Pavlichenko, L. (2022). Shaping the status trend of Covid vaccines on TikTok: Critical Discourse Analysis of bloggers’ videos. Current issues of Ukrainian linguistics: theory and practice, 47(3), 93-99. https://doi.org/10.24919/2308-4863/47-3-15

Redbubble (n.d., a). A nation of sheep mask [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.redbubble.com/i/mask/Anation-of-sheep-by-jeremyspokenin/39385341.9G0D8

Redbubble (n.d., b). I’ve been Pfizered [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.redbubble.com/i/mask/I-ve-been-Pfizered-II-by-flevin/76020321.9G0D8

Redbubble (n.d., c). Make politics boring agagin mask [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://acortar.link/ZC49a1

Redbubble (n.d., d). Obey Sheep Mask [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.redbubble.com/i/mask/Obey-Sheep-by-SteveGrime/48658694.9G0D8

Redbubble (n.d., e). Peace Love Vaccinate Mask [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://www.redbubble.com/i/mask/Peace-Love-Vaccinate-by-medbdj/90616039.9G0D8

Redbubble (n.d., f). Pfizer face masks for sale [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://ih1.redbubble.net/image.2359976425.3106/ur,mask_flatlay_front,product,600x600.u4.jpg

Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2017). The Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA). In Ruth Wodak & Michael Meyer (eds.), Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, 87,121. SAGE Publications, Ltd. http://doi.org/10.4135/9780857028020

Rose, A. (2020). A Paris Fashion Week attendee wears a Chanel mask [Photograph]. Footwear. Retrieved from: https://footwearnews.com/business/business/chanel-coronavirus-relief-efforts-1202956417/

Saris & Things. (n.d.). 4 Pk BLM Black Lives Matter Face Mask Reusable I Can't Breathe Face Cover [Photograph]. Retrieved from: https://acortar.link/o9Lzdc

Shirazi, F. (2003). The veil unveiled: the hijab in modern culture. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Tilstra, A.M., Polizzi, A., Wagner, S., & Akimova, E.T. (2024). Projecting the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. population structure. Nature Communications, 15, 2409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46582-4

UAB News. (2022). How the COVID-19 pandemic changed society. Retrieved from: https://www.uab.edu/news/youcanuse/item/12697-how-the-covid-19-pandemic-changed-society

Wong, J.C. (2021). The people who want to keep making: ‘It’s like invisibility cloak’. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://acortar.link/NstZE1

World Health Organization. (2020). Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. Retrieved from: https://acortar.link/blGoRm

https://amazoniainvestiga.info/ ISSN 2322-6307

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Reproduction, distribution, and public communication of the work, as well as the creation of derivative works, are permitted provided that the original source is cited.