DOI:https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2021.47.11.25

Language, culture, and image-driven interpretations in translation: A case for the university translation classroom in Ukraine

Мова, культура та кероване образами тлумачення у перекладі: досвід для університетського викладання перекладу в Україні

Abstract

In this paper, we develop a theory of image-driven interpretations for the translation studies domain. Interpretations make the core of translation and are explained in terms of mental images. An image-driven interpretation gives a meaning to a source-language word and finds in the target language the word to capture this meaning, which is a creative act and a cross-cultural transfer. An interpretation is ‘drawing’ images in the human mind by the powers of the mind’s representational content.

Our theory proposes a role for etymological insight in boosting translation students’ interpretive skills via exposed inner word forms. These archaic archetypal images contain culture-specific information transmitted through human generations with the help of language. Inner word forms are non-trivial triggers in cultural exposure that raise students’ awareness of the native and foreign cultures and add an in-depth dimension to regular vocabulary work and other good practices in the translation classroom. We pin down some of the influences that native Ukrainian words and borrowings have had on the Ukrainians’ interpretive mind.

Key words: cultural awareness, inner word form, interpretation in translation, mental image, word meaning.

Анотація

У статті запропоновано теорію керованого ментальними образами тлумачення у перекладі. Тлумачення розглянуто як творчий акт, за якого значення слова мови оригіналу представляється у мисленні як образ, що змальовує відповідний референт. Необхідність описати цей образ засобами мови перекладу скеровує пошук слова, значення якого представлятиметься у вигляді еквівалентного ментального образу. Тлумачення є ‘малюванням’ ментальних образів завдяки репрезентативному вмісту мислення.

Розвиток навичок тлумачення у майбутніх перекладачів розглядається як такий, що може бути підсилений шляхом залучення у словникову роботу етимологічно виявлених внутрішніх форм слів. Внутрішня форма слова є архаїчним архетиповим образом, який уміщує культурно-специфічну інформацію, передавану крізь людськи покоління за допомогою мови. Виявлення такої форми є нетривіальним способом розвинути образне мислення студентів і підвищити їхню чутливість до особливостей рідної та іншомовної культур. У статті простежено вплив власних слів і запозичень на тлумачення у перекладі з української мови.

Ключові слова: внутрішня форма слова, значення слова, ментальний образ, тлумачення у перекладі, чутливість до особливостей культури.

Introduction

In this paper, we address the issue of interpretive skills as part of translator competence and suggest a cognitively-inspired approach to words in the translation classroom that boosts these skills. Our suggestion rests on a theory of interpretation that we develop based on insights from the domains of cognitive linguistics, cognitive psychology, and philosophy of mind. We believe that interpretation that takes place in translation is a virtue of image thinking in humans and essentially is converting word meanings into image-like mental representations, and vice versa; interpretation is ‘drawing’ images in the human mind by the powers of the mind’s representational content. From this perspective, the quality of interpretive skills in translation students depends on how developed their image thinking is. Yet, translation defined in terms of cultural mediation adds into this dependence another ingredient. This is cultural awareness that sensitises students to the peculiarities of their native and foreign cultures and ultimately shapes their interpretations. Cultural awareness grows via students’ cultural exposure that has its breadth in terms of quantity and its depth in terms of quality of culture-related experiences.

The translation classroom therefore has the twin goals of raising cultural awareness and of promoting image thinking in students, which we assume to be interrelated since it is awareness that delivers into the mind the experiences that the mind interprets and construes as mental images. Ways to develop image thinking in humans are potentially many. This paper argues that from among these ways a reference to etymology is a good pick for the translation classroom. Elements of etymological analysis can in a rather straightforward way be embedded into vocabulary work. This analysis reveals the inner word forms in the native and foreign languages, which we suggest be used in the learning process. Inner word forms are the primary images that came to motivate words of this language at the moment of their creation in the archaic worldmodel. Inner word forms are culture-specific and have their roots in distinct cultural archetypes, which endows them with a subtle yet powerful influence on image thinking and offers the translation classroom non-trivial opportunities of in-depth cultural exposure.

The assumptions this paper makes are supported by evidence that comes from teaching various aspects of translation at some of the major universities in Ukraine. What generally prompted this paper is the poverty of interpretations and the culturally insensitive translations that in the last two decades have come to proliferate among the students, which is disquieting. With this concern in mind, we summarize and critically assess our research and teaching practice and make in this paper a case for wiring etymological insight into methodologies of vocabulary teaching for translation students.

Section 1 of this paper overviews some of the theoretical prerequisites for our research. Section 2 spells out the theory of image-driven interpretations that we suggest for the translation studies domain. The theory is underpinned by a discussion of the virtues of communication with words, with a focus on the role that inner word forms have in this communication (Section 3). Section 4 examines the nature of inner word forms and fleshes out the methodological solution that we offer. Section 5 looks at the case-based evidence and its implications for our research. We generalize over a number of educational environments for translation students in Ukraine and from a historical perspective pin down some of the influences that the Ukrainian language has had on the Ukrainians’ interpretive mind (Section 6). Section 7 draws the bottom line and specifies the approach we suggest. This paper concludes with prospects for further research.

Theoretical framework

- Developing interpretive skills in translation students: some theoretical prerequisites

- A theory of interpretation that gives credit to image thinking in translation

- Human communication with words and the role that inner word forms play in it

In this paper, we assume that inherently there is a connection between the mechanisms of awareness and of interpretation in the human mind. Without awareness, there is no conscious experience; awareness steers an experience to emerge into consciousness and makes this experience available for interpretation and verbal report (Chalmers, 2004). This implies that one’s interpretive skills generally are sustained by amounts of awareness one has. For translators, these are amounts of cultural awareness since translation is cultural mediation.

Culture is neither artifacts nor people but their arrangement into a harmonious whole. Culture manifests itself in language that endows the community with means of (self-)expression. Culture licenses interpretations, shapes communication, and frames social contexts for it (Larson, 1984). Cultural awareness is treated in this paper as a sensitivity to native and foreign cultures that one develops through exposure to these. A robust awareness of culture like a compass navigates the cultural worldviews mediated in translation. Culture is not inborn but learned through diverse experiences that trigger an awareness and an understanding of the norms, behaviors, values, and beliefs found in this culture. These experiences constitute cultural exposure.

Exposure both to native and foreign cultures is critical for translators. It must be of a sufficient breadth and of an absolute depth, which stands respectively for the quantity and quality of exposures (Crowne, 2013). The translation classroom is an environment that gives students an experience different from travelling or staying abroad. Its advantages are general availability, controllability, facilitation, and aptness to address specific educational concerns. In particular, the classroom offers unique opportunities to employ triggers calibrated in expert theorising and research (Bashkir et al., 2021). The triggers this paper advocates are inner word forms and their regular injections into vocabulary work. This is word knowledge available to professionals. At the same time, by virtue of the cultural archetypes that inner word forms ascend to, this is part of the collective unconscious in humans (in Jung’s terms). The methodological solution that we offer in this paper sits on the qualitative dimension in cultural exposure and works with the in-depth capacities of interpretation.

The term translation is used in this paper to refer to ‘the transfer of thoughts and ideas from one language (source) to another (target), whether the languages are in written or oral form; whether the languages have established orthographies or do not have such standardization or whether one or both languages is based on signs, as with sign languages of the deaf’ (Brislin, 1976, p. 1), which affords a broad view of translation as, first, ‘intralingual translation, or rewording, as interpretation of verbal signs by means of other signs of the same language’; second, ‘interlingual translation, or translation proper, as interpretation of verbal signs by means of some other language’; third, ‘intersemiotic translation, or transmutation, as interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems’ (Jakobson, 1959, p. 233).

In this light, the core of translation is interpretation as ‘the act of construing or understanding something in a particular way’ (Kipfer, 2019). Interpretation gives a meaning to or provides the meaning of something. The term interpretation is used in this paper with reference to representational properties of the human mind. We believe that interpretations in translation rest on converting the mind’s phenomenal content into its propositional content. This in essence is converting a non-conceptual mental representation into a conceptual one. Non-conceptual mental representations are image-like, holistic, and ineffable; conceptual mental representations are decomposable into constituents, they make up the propositional thought and underlie human languages (Kosslyn, Thompson, & Ganis, 2006), cf. the phenomenal experience of seeing that this tree is green vs. the thought that this tree is green.

Mental representations are entities that emerge in the human mind in interactions with the world. They are internalized symbols for this world’s entities in the mind. Mental representations are inherently conscious: humans normally are aware and capable of responding to them (Chalmers, 2004). Directed at mental representations is the mind’s eye, cf. the mentis oculi in Cicero’s ‘the eyes of the mind are more easily directed to those objects which we have seen, than to those of which we have only heard’ (cited from Watson, 1875, p. 239). Humans ‘see’ the images their minds contain.

Visual representations prevail in the mind, though the other senses might contribute. Mental images depict the world, whereas languages describe it, which also has a different brain substrate. Stimuli in reading bring mental images to mind. Non-existent entities are perceived and interpreted by the brain/mind in the same way as real ones. Owing to such substitution effects, mental images evoke the same or similar cognitive, physiological, and behavioral response as the actual entities they depict.

Mental representations tie in with imagination and creativity. High-image individuals report bigger amounts of imaginative and creative thinking as compared to low-image individuals (McKellar, 1957). We believe that high-image thinking is the sine qua non for translators because of their active and creative role in communication across cultures: ‘the most competent translators possess a malleable and creative mind’ (Wilss, 1996, p. 167). This belief is the driving force for this paper.

Translation is interpretation and not re-writing: not a word-to-word but an image-to-word correspondence, with the understanding that this image is a construal in the interpretive mind. A translator needs to internalize the authors’ mental images in reading and to find the words in the target language in order to re-’draw’ these images. While mental images are individual, words are communal, which generally makes communication possible.

Human language is a sign system whose cardinal elements are words and texts: whereas a word unfolds into and generates a text, the text is capable of folding back into the word that has generated it (Svatko, 1994).

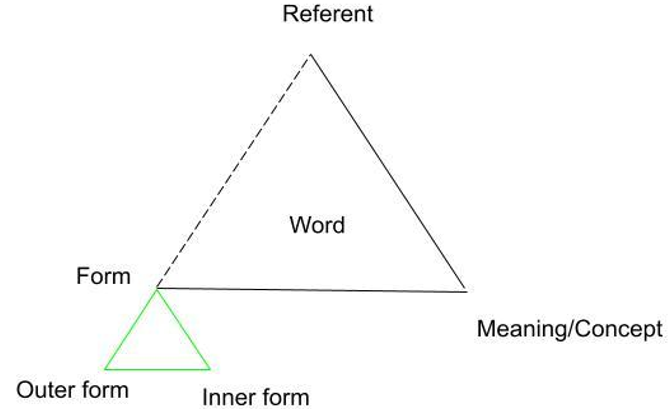

Similarly to the human mind that maps the world, language maps the information in the mind. A map ‘is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness. <…> If we reflect upon our languages, we find that at best they must be considered only as maps. A word is not the object it represents’ (Korzybski, 1994, p. 161). Linguistic semiosis involves a three-stage mapping: concepts in the mind are subjective construals that reduce information about the world to its salient features; word meanings expose in concepts their salient features; inner word forms are salient fragments of word meanings. Figure 1 captures this idea and is an elaboration of the semiotic triangle (see Ogden, & Richards, 1923).

Figure 1. Word as a sign.

The black solid lines in Figure 1 stand for relations between a referent and the word meaning and between the word form and word meaning. These relations are immediate. The black dotted line stands for the arbitrary relation between a referent and the word form and, indeed, there is nothing in word forms that resembles their referents, except in onomatopoeic words. Humans in communication use word forms that relate to word meanings and concepts but not to referents. Words manifest the speaker’s concepts and activate the listener’s ones. Concepts captured by words become the meanings of these words. Words therefore round concepts to meanings, with the implication that some part of the mind’s content will always remain beyond linguistic description (see Vakhovska, 2017 for detail), which also is a limitation in translation.

The green triangle represents the inner and outer word forms. The outer form is the word’s phonemic or graphemic container. A fragment in word meaning that comes to motivate this word at the moment of creation is the inner form of this word (Potebnya, 1989). Inner forms are overt in some and covert in other words, which distinguishes synchronically motivated vs. non-motivated words. Diachronically, all words are motivated; their inner forms can generally be discovered via etymological analysis.

The BEAR concept, for example, is the information about bears as a species available to an individual and stored in their mind. The English noun a bear has the meaning ‘any of the plantigrade, carnivorous or omnivorous mammals of the family Ursidae, having massive bodies, coarse heavy fur, relatively short limbs, and almost rudimentary tails’ (Kipfer, 2019). This meaning exposes in the concept some of its salient features, while various other features such as the natural habitat or one’s experience with bears remain hidden. The etymon of a bear is the Proto-Indo-European root *bher- ‘a creature that is brown or bright’ (Onions, 1966), which reflects sacred properties ascribed to totem bears in the Proto-Germanic worldmodel: ‘brown fur of the mighty animal as if that touched by the sun’. The brown colour and brightness are the inner form of the noun a bear; as visually perceived properties, they are image-like mental representations of this animal. The root *bher- is synchronically covert, however, and even for native speakers, unless with expert knowledge, there is nothing in the word that points at the motivator.

The inner form of the Ukrainian noun ведмідь ‘a bear’, on the contrary, is overt (Melnichuk, 1982-2006) and native speakers readily recognize the motivator: the roots мед ‘honey’ and *ěд- ‘to eat’ with the meaning ‘a creature who eats honey’. The colour and food habits are only fragments of information generally known about bears. These fragments had a cultural salience and at the moment of the words’ creation were chosen to represent and evoke in the mind the whole information about bears. These choices show the culture-specific ways bears were ‘seen’ in the Proto-Germanic and Proto-Slavic world models. Pictorially, these are different bears, which has implications in the national cultures, in particular the symbolism of berserkers, or bear warriors, is at large absent from the Slavic culture.

Methodology

4. Inner word forms as seed images and their relevance for translation

In this paper, we treat inner word forms as seed images from which mental representations of different amounts of pictorial richness have the potential to evolve, and into which mental representations can shrink. We find inspiration for this treatment in the domain of nature with plants growing from seeds and in artificial intelligence where a seed AI is ‘an artificial general intelligence which improves itself by recursively rewriting its own source code without human intervention; it understands its own source code and knows its purpose, syntax, and architecture’ (Yudkowsky, 2001).

Culture is ‘the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another’ (Hofstede, 1991, p. 5). Culture is a software for the hardware to work in a peculiar way. Inner word forms are gene-like codes with culture-specific information transmitted through human generations via language. Cultivating these seeds in the translation classroom will improve students’ language competence and give richer interpretations.

The term inner word form ascends to inner form of a language (in German, innere Sprachform) that has a central position in W. von Humboldt’s philosophy of language. An inner form is an active force that ‘gives form to the raw material’ (Leopold, 1929, p. 254) and endows this material with a life. The inner form of a language is a national spirit (Volksgeist) locked up in the architecture of this language. It shows how this nation ‘sees’ the world.

A language has a symbolism of its own that, for Potebnya (1989), emerges from a poeticity (poetic here means ‘archaic, traditional, laden with cultural value’) this language derives from myths in the pre-writing world model. Words with their inner forms capture the myths. An inner word form is a poetic image; it is intangible and has the property to seem only, there is no fixed and rigorous semantics in it. It is not a meaning itself but the seed from which this meaning is generated together with a set of potential meanings. It is the probable semantics related to cultural archetypes. It manifests a peculiar ethos as the fundamental traits and spirit of a culture (ibid.). As a result, inner word forms enliven the language with peculiar cultural connotations and with a cultural spirit.

In this paper, we assume that, metaphorically, the wine is more precious than the bottle that contains it: in translation, the interpretation of a word or a text is the spirit of their content that can by no means be lost. A good translation is pouring the wine from one bottle into another without evaporating the spirit - the wine does not turn into water. We suggest this metaphor be communicated to translation students.

The methodology we offer has originally been tailored to the benefit of the Ukrainian students enrolled in some of our authored English translation courses: Introduction to Translation Studies, Theory and Practice of Translation, and Literary Translation. Our experience holds implications for translation studies research. These are summarized below.

Results and discussion

5. Translating from Ukrainian into English in the face of modern Ukrainian culture: what language do we actually translate from?

Translation theory and teaching practice make us think that a translator’s competence depends largely upon their native language competence, while this very sort of competence in Ukrainian students of translation appears fairly weak, which we believe is caused by the loose national language situation in the country.

Translation students naturally are part of the general population. The general language situation in modern Ukraine is that of chronic instability and lack in scientifically grounded systematic policies when it comes to regulatory decisions of the state. The Ukrainian language competence in speakers of Ukrainian proves insufficient and low (Sokolova et al., 2013), which hurdles everyday communication and disserves education on the national scale.

The translation classroom in Ukraine is an environment where students are taught foreign languages with the aim of cultural mediation, while competence in Ukrainian is taken for granted, which we believe is wrong to take. We as teachers witness low Ukrainian language competence to postpone the classroom’s positive effects. Ours has been the translation from Ukrainian into English class, and we want to emphasize that today Ukrainian-English translation operates not only across the native and foreign languages but also across native and borrowed words in Ukrainian as in the source language of this translation. Borrowed words make up the surzhyk that impairs Ukrainians’ native language competence: speakers, because they do not know the words’ original meanings, misunderstand and misuse words - words in Ukrainian. This may go unnoticed in discourse, with speakers having an illusion of communication but in fact remaining in their isolated possible worlds.

Surzhyk (etymologically, ‘wheat mixed with rye’ as in mangcorn) is a mixture or, rather, a medley of languages; in Ukrainian linguistics, the term traditionally is used for the postcolonial mixture of Russian and Ukrainian. Today, cultural influences have shifted towards English, with educated Ukrainians using English-based surzhyk to indicate their intellectual excellence and social status: Якіівентивибпропонувалипроводитизбегіннерами? - Окрімузуальнихівентів, можнапроводитиворкшопи (Jaki iventy vy b proponuvaly provodyty z beginneramy? - Okrim usualnykh iventiv, mozhna provodyty workshopy) (Prof. T.Ye. Nekryach, personal communication, July 2021). The point is that English words are borrowed into Ukrainian as morphological and semantic cripples that as a mass debilitate Ukrainian speech.

In this paper, we stress the semantic transformations word borrowing may bring along. Borrowed words have their inner forms in respective source languages. As a rule, in target languages these forms are lost (Abaev, 1948): etymological motivation of English borrowings remains covert in Ukrainian, while their sound form can resemble that of certain native words. As a result, speakers ‘see’ what borrowings seem and superimpose semantic illusions on their interpretations. The now-fashionable Ukrainian word візія ‘a point of view, an opinion’, for example, takes on an illusion via associations with візит‘a visit’ or ревізія ‘an audit’. Another example is івент‘an event’ - a translator’s non-trivial task since one does not know if what the speaker means correlates with an event in English or not. Or OK that has modified into океюшки with the meaning ‘not merely good but to mean that I like you’ - its back translation cannot be OK anymore since this would rob the word of its heuristic value in the Ukrainian culture.

Does a translator have the right to translate such words? How does a translator have to translate them? Is this translation from Ukrainian? Answers to these questions are not straightforward (cf. Karabulatova et al., 2021). In the meanwhile, Ukrainian students report an urge for their native language competence to be repaired and improved (Sokolova et al., 2013). We believe teachers of translation must themselves be word-conscious in order to be able to repair native language incompetence in their students (see Budnyk et al., 2021). Similarly to talking cure when a psychotherapist via words brings a patient back to the root of the problem and forward to a new reference point (Jusuk, & Vakhovska, 2021), a translation teacher must be able to bring their students back to word origins and forward to increased amounts of word understanding: this sort of clarity has a strong influence upon the interpretive mind. Words’ original meanings must be sifted out of semantic illusions, and only on the basis of good interpretations must meanings be put into words.

Our etymology-based approach to words and to vocabulary teaching responds to these signals. We believe that in the translation classroom words - both native and foreign - must be taken by the piece and for each word an account must be given in terms of this word’s etymology and meaning. In this manner, words will be planted into their cultural soil and richer interpretations will be harvested from them.

We did an etymological survey of the Ukrainian word-stock to show that an account of this kind, both synchronically and diachronically, fits the translation classroom’s agenda.

6. Ukrainian and the Ukrainians’ interpretive mind: a historical perspective

Our survey was fueled by a direct simple random sample from three sources intended to secure historical bearing for our assumptions. Hrabyanka’s Litopys (Hrabyanka, 1710) is a piece of Ukrainian historical prose written in the short spell favourable for the national culture. By then, Poland’s influences had ceased and those of the Russian Empire had not yet come off. It is an exceptional specimen of the Ukrainian Baroque culture (Pishchanska, 2016) written in Old Ukrainian instead of Old Church Slavonic, which supported its traction with the people (Sukhyi, 1996). Rada (Matushevsky, 1906) was the first and for a long time the only Ukrainian daily newspaper in central Ukraine in the early XX century. It reached a large audience and had a strong formative influence upon the emerging national identity (Krupskii, 2004). Khreshchatyk (Petryshyn, 2021) has a general social and political agenda and is a modern weekly Kyiv-based Ukrainian newspaper.

Ours is a set of ca. 3000 words from each of the sources, which generally corresponds to core benchmarks in language competence (see Schmitt, 2008). The language of our sources was/is spoken by the average population, was/is not a dialect, and was/is colloquial, which we intend to minimize authors’ individuation in discourse and to bring our sample close to the national oral tradition. Overall, there are 8783 words in our data. An etymological dictionary of Ukrainian (Melnichuk, 1982-2006) was used to reveal the word origins. Table 1 summarizes our findings.

Table 1.

Etymological makeup of the Ukrainian language from a historical perspective.

The data indicate that the Ukrainian cultural soil is full of foreign seeds. These are inner forms planted in Ukrainian via borrowed words: if the original motivators and meanings of these words are not clarified, one cannot positively tell a weed from a crop in interpretation. Another indicator is shifts in the Ukrainian etymological make-up that show the ethos and national spirit (Humboldt’s Volksgeist) Ukrainians as a community lean towards: the growing Latinization in the data sides with our discussion of surzhyk (Section 5 of this paper).

On that, teaching robust etymological awareness to translation students in Ukraine becomes a fundamental need: to not lose the spirit of the words’ content, one must go deep to the etymological roots. We suggest this table be presented to translation students against the background of the theory this paper develops.

7. Etymological probes that make the translation classroom into a laboratory

Word etymologies as archaic memories make up the community’s cumulative experience. Though etymologies of native words integrate into native language competence, one’s awareness of them may be absent or low (Abaev, 1948). We suggest this be increased by introducing elements of etymological analysis into relevant kinds of vocabulary work.

A bottleneck in translation is cultural differences. The translation classroom will turn into the translation laboratory if in it cultures are protected from genetic modifications, and weeds of semantic illusions are separated from crops of original meanings. We recognize that ‘culture-bound words and concepts pose a major challenge even to the experienced translator’ (Zethsen, 2010, p. 555). One might expect these are exotic words. Yet, these often are everyday words like bread that in fact name culture-specific concepts (Benjamin, 2000). Whereas etymological analysis generally exposes the origin and evolution of words in a language, we choose to focus on the capacity that this analysis has in terms of revealing the inner word forms as seed images for image-driven interpretations.

Our approach is a two-facet etymological probe into each target word, as well as into its translation equivalents, for (1) the word origin and (2) the word etymon. Whereas word origins help to plant words into their distinct cultural soils, word etymons expose inner word forms and help these seed images to grow into students’ good interpretations once the teacher’s commentary is available and the overall etymological experience accumulates into an intuition. Inner forms exposed in parallel in native and foreign words connect students back to the native culture and give an unprecedented insight into the foreign culture. Specifically, a probe of this sort is what we do with the words a bear and ведмідь in Section 3 of this paper. On that account, etymological dictionaries must be given the same regularity and value in the translation classroom as ordinary dictionaries.

Etymological probes fit into both intentional and incidental vocabulary instruction and learning (see Schmitt, 2008), with words looked up in dictionaries and their etymologies and meanings negotiated. The time students spend engaging with the probes is in classroom activities that maximize repeated exposure to the target etymologies: inferences from contexts, eliciting synonyms and antonyms, making glosses and dictionary routes, etc.Conclusion

This paper has shown that translation is not a matter of knowing many words; it is a matter of going deep into their meanings so that the spirit of their content is not lost. The assumptions this paper makes are relevant for literary translation in the first place. The prototype of fiction literature is national oral tradition. National oral traditions are pictorial; they ‘draw’ images in the mind with the help of words. We suggest national oral traditions be included into translation students’ background reading. This is not plain reading but intellectual work for the interpretive mind. Apart from improving skills of interpretation, ‘drawing’ images in the mind boosts general intelligence and creative thinking in students.

This paper primes the curriculum we intend for the university translation classroom in Ukraine. This will include a lecture course, seminars, and workshops based on the translation theory and methodologies defined in this paper. The curriculum is envisaged as customizable to fit other national translation classrooms.