DOI: https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2021.42.06.12

Experiencing and overcoming financial stress in married couples: A study in COVID 19 pandemic era

Переживання та подолання фінансового стресу в сімейних парах: Дослідження в епоху пандемії COVID 19

Abstract

The article analyzes interaction of spouses in overcoming financial stress. An online survey of 136 married couples was conducted during the lockdown caused by the spread of COVID-19 accompanied by family income losses. Frequency and severity of discussions on financial topics; level of subjective economic well-being, activity of coping strategies, family cohesion and adaptation were measured. Results showed that the discussion of financial topics is a stressor for married couples, accompanied by contradictions and conflicts, but ultimately helps to improve quality of relations between spouses, and also increases the adaptability of the family system in a situation of socio-economic crisis. Subjects of conflicts were defined. Influence of gender roles on financial consciousness and behavior was shown. Wives are more likely to initiate discussions on economic topics and more inclined to economic anxiety, while husbands showed economic optimism. The severity of financial stress correlates with assessments of family cohesion. Correlations between financial well-being and coping behavior of husbands and wives represent the family as an entire open system. Partners are interdependent in overcoming financial stress. Collective family coping is determined by individual reactions of spouses. The efforts of partners can be congruent and complementary.

Keywords: financial stress; coping behavior; family relationships; joint coping; subjective economic well-being.

Анотація

У статті проаналізовано взаємодію подружжя в подоланні фінансового стресу. Інтернет-опитування 136 сімейних пар було проведено під час локдауну у зв’язку з поширенням COVID-19, що супроводжувався втратами доходів сім'ї. Визначено частоту та гостроту дискусій на фінансові теми; рівень суб’єктивного економічного добробуту, активність стратегій подолання, рівень згуртованості та адаптації сім’ї. Результати показали, що обговорення фінансових тем є стресовим фактором для сімейних пар, що супроводжується суперечностями та конфліктами, але в кінцевому рахунку сприяє поліпшенню якості відносин між подружжям, а також підвищує адаптивність сімейної системи в ситуації соціально-економічної кризи. Були визначені предмети конфліктів. Показано вплив гендерних ролей на фінансову свідомість та поведінку. Дружини частіше ініціюють дискусії на економічні теми і схильні до економічної тривоги, тоді як чоловіки демонструють економічний оптимізм. Тяжкість фінансового стресу співвідноситься з показниками згуртованості сім'ї. Співвідношення між фінансовим благополуччям та поведінкою чоловіків та дружин у процесі копінгу (подолання) представляють сім'ю як цілісну відкриту систему. Партнери взаємозалежні в подоланні фінансового стресу. Колективний сімейний копінг визначається індивідуальними реакціями кожного з подружжя. У своїх діях партнери можуть або суперечити одне одному або доповнювати один одного.

Ключові слова: фінансовий стрес; копінг-поведінка; сімейні відносини; спільний копінг; суб'єктивне економічне благополуччя.

Introduction

Our study is topical and important primarily because of the global economic downturn due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, humanity plunged into a new social crisis, which proved to be long and affected all aspects of life. Due to the introduction of lockdown, many people were forced to limit their social contacts and professional activity, so they lost part of their usual income. As a result of the closure of many industries, workers were often sent on unpaid leave or fired. This is an unprecedented event with the financial, physical and mental consequences comparable with the Great Depression (Center for Financial Social Work, 2020). Although the economic consequences are quite obvious, the psychological effects need in-depth study, as financial stress has increased psychological vulnerability in this emergency. The pandemic has posed a number of serious challenges to the scientific community, but it has also created unique conditions for monitoring the development of stress reactions and their consequences, including a deeper study of the financial crisis in families.

Meeting the economic needs of a person is one of the most ancient, basic functions of the family as a social institution. Creating a family involves not only the emotional, psychological and sexual intimacy of two people, but also financial partnership. This task provides for material support, distribution of funds, joint housekeeping, creating economic conditions for a comfortable life, caring for disabled family members, investing in the future and much more (Zmanovskaya, 2020). But the economic aspect of living together often causes tension, developing into a source of chronic conflicts, reducing satisfaction with a relationship and leading to a breakup. Money takes a leading place in the ranking of family problems — 42% of respondents over 30 years of age mentioned them in the study of prosperous urban families (Kartashova, 2013).

The research is intended to find out the features of experiencing and overcoming financial stress in married couples. We posed two questions. First: how did the lockdown situation affect the economic well-being of Ukrainian families? Second: how are coping and communication strategies for men and women about financial issues related to their SEW level? Our study was conducted in special conditions — during the lockdown in 2020, when most Ukrainians were affected by stress factors of irresistible force. This allowed us to study reactions to stress directly when experiencing it. In contrast to previous studies, partner behavior was not only compared in terms of gender differences, but also viewed as a whole. Considerable attention was paid to detailing the idea of the functioning of the family as a system — a demonstration of the interdependence of the partners’ behavior in a situation of financial stress.

The results obtained will help to understand the psychological characteristics of economic consciousness and personality behavior in a changing crisis society, as well as the general trends of joint family coping with financial stress. These data will be useful for family counselors to gain a deeper understanding of the causes of disturbances in marital relations and to develop particular recommendations.

Literature review

Davis and Mantler (2004) defined financial stress as “the subjective, unpleasant feeling that one is unable to meet financial demands, afford the necessities of life, and have sufficient funds to make ends meet (e.g., have to reduce standard of living).” This definition corresponds to a wide range of situations: job loss, sharp decrease in income, debt, forced heavy expenses, investment losses, etc. Financial stress tends to become chronic, and its causes can be either external (regional economy) or internal: poor management of your finances, high level of ambitions, propensity to spend, fear of poverty, etc. Economists are interested in the objective characteristics of such a crisis (household income relative to regional norms and the dynamics of its decline), while psychologists pay attention to the subjective characteristics of financial stress and the accompanying factors. Like any distress, financial problems are accompanied by many biochemical, physiological, emotional reactions, cognitive and behavioral changes.

Most studies of the negative effects of financial stress on an individual focus on a particular type of economic difficulties; the negative effects of unemployment are studied most often. Numerous empirical data show similar results in different historical circumstances and in cultures — both in industrialized countries and in poor unstable economies (Blair, 2012; Conger et al., 1993; Frankham, Richardson & Maguire, 2020; Jahoda, 1988; Liker & Elder, 1983). Unemployment has great subjective significance and personal meaning — this is not just a loss of income, but also the loss of familiar social contacts, daily activities, life goals and landmarks (Chuykova, 1997).

Individual effects of financial stress include short-term acute states and delayed reactions: fear, anxiety, concern about the future; shame and guilt; hostility towards oneself, other people, and the world at large; deterioration of self-control, a feeling of self-failure; decreased self-esteem and self-respect; the formation of a pessimistic outlook on life; loss of professional identity. The core effect of financial stress is a high level of depression, which deprives people of the joys of life, with significant motivational, cognitive and behavioral consequences (Frankham et al., 2020). The statistics of developed industrial countries are indicative in this regard, which shows that the deterioration of economic indicators (population income, unemployment rate) is accompanied by an increase in overall mortality and mortality caused by cardiovascular diseases, an increase in the number of suicides, the number of voluntary and involuntary patients in psychiatric clinics (especially men), the criminalization of behavior and an increase in the number of prisoners, increased use of drugs, cigarettes and alcohol, an increase in the proportion of alone people (Davis & Mantler, 2004).

The works of Conger, Ge et al. (1994) and Conger, Lorenz et al. (1993) examined the mechanism of the influence of economic problems on family relationships. It was shown that the effects of financial stress are different for men and women: husbands experience depression, anxiety and hostility, while family stressors (depressed hostile husband) that cause depression, anxiety and physical health disorders, are more significant for wives. Financial stress directly affects the breadwinner’s main income, thus indirectly affecting family relationship, which in turn affects children. So, family problems form a cycle and exacerbate primary stress. In situations of financial difficulties, anxiety in men is regulated by the quality of family and social support (Tran et al., 2018).

Economic stress increases the likelihood of family disagreements (Conger et al., 2010). Couples may experience anger, frustration, depression, and often argue over money; they become estranged, offer less emotional support and care. As the stress response deepens, conflicts begin to be accompanied by criticism, blaming, aggression, which further reduces satisfaction with the relationship (Davis & Mantler, 2004). The severity of depressive reactions affects the ability of partners to help each other, exacerbates the irritable and hostile style of interaction. On the other hand, partners’ reactions to financial difficulties depend on how satisfactory their relationship has been before (Liker & Elder, 1983). Karademas and Roussi (2016) emphasize the importance of dyadic coping for adapting a couple to financial stress.

To understand the conditions for overcoming financial crises in families, the concepts of dyadic coping are useful, combining the provisions of the theory of family systems and the theory of coping resources (Bodenmann, 2005; Kuftyak, 2012). In dyadic relationships, subjects respond to the stress factor as units of interpersonal interaction, and not as individuals isolated from each other — they are dependent in reactions. To explain these dependencies, the scholars developed various theoretical and statistical models (Iida, Seidman & Shrout, 2018; Karney & Bradbury, 1995; McCubbin & Patterson, 1983). A lot of publications deal with the study of coping in married couples; however, almost all of them are focused on the joint experience of life-threatening illnesses or parenthood problems, and do not reveal the topic of financial crises.

Financial stress significantly worsens parent-child relationship and reduces the quality of parental care. In men, low income is associated with a loss of power and status in the family, in women — with maternal depression. Because of hostility, despondence and depression, parents are less likely to respond to the needs of their children, become less optimal and consistent in educational strategies. The risk of child abuse increases. On the other hand, adolescents have their own interpretation of the financial problems of the family; they feel constraints in satisfying their material needs. All this leads to a number of social and psychological problems of children: low self-esteem, depression, impulsive and deviant behavior, poor academic performance, drug and alcohol use, and rejection of social relations. Children can take over the pessimistic worldview of their parents, lose their sense of personal competence and control over their lives, and copy lower expectations about their careers (Conger et al., 1994; Davis & Mantler, 2004; National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2020; Shelleby, 2018; Takeuchi, Williams & Adair, 1991).

Given the seriousness of the described consequences, it is surprising that the problems of financial stress in the family so rarely become the subject of research. Paradoxically, the topic of finances is still taboo and not discussed in the Western culture, despite the fact that society as a whole recognizes the use of money as a criterion of social stratification and identification. There are a number of psychological and cultural reasons for this failure to mention, such as inequality in wealth, self-preservation and protection of fragile identities, and equating the value of an individual with financial status (Pinsker, 2020). Failing to mention money leads to the fact that when getting married many couples are not ready for an open discussion of their financial behavior, needs and expectations; later the spouses do not know each other’s real income and expenses, and the children are not told about how their parents earn. As a result, many people feel uncomfortable discussing their financial life, especially its problematic aspects. On the other hand, it is the crisis that can trigger an open dialogue about money. Lack of skill in discussing economic issues should be taken into account both in financial counseling and in providing psychological assistance to families (Alsemgeest, 2016; Trachtman, 1999).

The psychological approach to the study of economic consciousness and behavior is based on the provision that experiencing well-being is more subjective than an objective phenomenon: the formula “to be economically challenged means to have a low material standard of living” is incorrect and does not correspond to life realities (Khashchenko, 2011). Indeed, often low-income young people are happier and more satisfied with marriage than wealthy adult families. It long been known that satisfaction with the material situation is determined not so much by the level of income as by the conformity of a person’s financial status to his/her needs, ambitions and demands (Ackerman & Paolucci, 1983; Strumpel, 1974), as well as comparison of one’s situation with the financial situation in the reference group among similar or reputable persons (Campbell, 1976).

The issue of “subjective poverty”, which is interpreted as subjective economic stress — a feeling of inadequacy of one’s own material capabilities that dominate the society’s living standards and social criteria: consumption, labor, leisure and lifestyle — is increasingly being discussed (Bienkunska, 2018). Subjective poverty is based on reduced self-concept, supported by the social environment, which ultimately blocks personal motivation (Muzdybaev, 2001).

In this context, a methodology for measuring subjective economic well-being (SEW) — a generalized perception and experience by people of their financial situation and material living conditions — is quite useful. The experience of subjective well-being is determined by conventional socio-cultural standards of welfare, a system of person’s attitude, individual values and goals, as well as expectations and fears about the future. The measurement of SEW is based on a number of cognitive and emotional components: reflection of current well-being, belonging to a certain economic social category; assessment of the favorability of living conditions; assessment of the adequacy of income, taking into account material, social needs and the needs of self-development; the severity of economic difficulties and the accompanying emotional states; the individual’s attitude to himself/herself as an economic entity, which includes aspects of business activity, achievements and ambitions; attitude to money, their value-semantic meaning for a person (Khashchenko, 2011; 2012).

Actual and subjective economic well-being determines the overall quality of life, the level of psychological well-being and human happiness (Veenhoven, 2018). On the other hand, it is an independent factor in determining behavior, the value of which increases or decreases at different periods of life (Easterlin & Sawangfa, 2007).

All of the above indicates that financial issues are not only an economic, but also a psychological category related to needs, values, and social standards. The family’s financial well-being reflects the level of income and consumption, the ambitions and expectations of partners, as well as how they interact in resolving financial issues. An important aspect of the psychology of financial stress is coping — conscious or spontaneous actions aimed at overcoming external and internal demands, which are assessed by a person as significant, superior to his/her capabilities (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). This issue has been little studied with regard to financial stress.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 136 Ukrainian married couples (136 men and 136 women) who were in a partnership from 4 to 15 years. Of these, 104 (76.5%) were in a registered marriage; 32 couples represented civil unions, that is, they were not legally married, but constantly lived together and run a joint household. The age of respondents is from 24 to 40 years (average age of men is 33.8, that of women is 32.6). There were 37 couples who had no children, 48 couples had one child aged 1.5 to 14, 44 couples had two children, 7 couples had three or more children.

The level of joint monthly income for families ranged from 350 to 2,000 USD (at the time of the survey the legislatively established minimum wage in Ukraine was about $180). The average monthly household income in the sample was $556±102, with asymmetric shifted to the left.

Measurements

Studying financial behavior in families

At the beginning of the study, participants were interviewed about their family’s financial status. Partners jointly answered questions about what is the average monthly household income over the past year (including wages, social benefits, property income, financial support from relatives, and other income); what is the individual contribution of the spouses to the total income of the family; how does family manage the budget and make financial decisions. A separate issue was about how has the quarantine situation affected family income and expenses?

A short questionnaire was developed, figuring out how often the family has discussions, disputes and disagreements on various financial issues. Respondents were offered a list of topics that they could supplement on their own (Table 1 of the “Results” section reflects the content of the questions). To assess the frequency of discussion, we used a 5-point Likert scale: 4 — a permanent source of discussion in the family; 3 — quite often; 2 — sometimes, several times; 1 — very rarely, once; 0 — never. We proposed to assess the severity of the conflict (tension, soreness of discussion) using a bipolar scale, where a +5 rating means positive emotions, ease of discussion and joint decision making; 0 means neutrality, lack of strong feelings; -5 — maximum severity of negative feelings and emotions, discussion of these issues causes stress in partners.

Subjective economic well-being

The questionnaire for measuring subjective economic well-being (SEW, Khashchenko, 2011) allows studying the life position of individuals in the field of material consumption. The methodology consists of 22 direct and indirect questions clarifying a person’s attitude to the financial and economic aspects of his/her life. Different scaling techniques are proposed for each item. Processing scores gives an integral indicator of SEW and indicators of five subscales: 1) economic optimism — the expectation of changes in their financial situation and the favorable external economic conditions; 2) the current well-being of the family — a subjective assessment of the material and financial situation; 3) subjective adequacy of income — the degree to which income meets the leading needs; 4) financial deprivation— the degree of subjective lack of financial resources, awareness of financial restrictions; 5) economic anxiety (financial stress) — the severity of negative emotional states in connection with material problems, concern about the future, the need to increase income.

The factor structure, reliability and validity of the questionnaire were proved on the samples of representatives of different social and professional groups (Khashchenko, 2011; Plotnikov & Sperlin, 2014). In the current sample, the internal consistency of individual scales ranged from 0.78 to 0.92; Cronbach’s alpha for the integral indicator of SEW was 0.85. SEW scores ranged from 48 to 86 points (mean 63.58 ± 7.15); the data distribution met the criteria of normality (Z Kolmogorov-Smirnov 1.16 at p = 0.12).

Ways of coping

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) by Folkman and Lazarus (1988), and a Russian-language adaptation by Kryukova (2010) were used. The methodology contains 50 questions describing a wide range of thoughts and actions that people use to manage the internal and external requirements of stressful situations. The questionnaire does not diagnose persistent behavioral styles; it is aimed at measuring the process of coping in particular circumstances. Respondents were asked to recall the difficulties and stresses that they had to face during the quarantine month and describe the ways in which they dealt with them. Four possible answers are proposed: never, rarely, sometimes, often (from 0 to 3 points). The technique allows assessing the severity of eight scales: confrontive coping — active efforts to change the situation, which involves a certain degree of aggressiveness and impulsiveness; the search for social support: informational, effective and emotional help from other people; planning a solution to a problem; self-control — efforts to regulate one’s feelings and actions; distancing involves cognitive efforts to separate from a situation and reduce its significance; positive revaluation — efforts to create a positive sense of the situation, focus on the growth of self; acceptance of responsibility — recognition of one’s role in the problem; escape — mental aspiration and efforts aimed at avoiding a problem: fantasizing, eating, alcohol, etc.

As the scales contain a different number of questions, we calculated relative scores as the average score for the subscale: the sum of the assigned scores divided by the number of questions. This allowed us to interpret the severity of coping strategies based on a single measuring scale from 0 (never) to 3 (often). The obtained estimates in the sample were distributed normally; Cronbach’s alpha values indicated sufficient internal consistency (0.77 to 0.96 for individual scales).

The interaction of partners in the family system

The FACES-3 Family Adaptation and Cohesion Scale was developed on the basis of the Circumplex Model of Family Functioning (Olson, 1991), which measures two main parameters of family behavior — family cohesion and adaptation. The indicator of family cohesion expresses the degree of emotional relationship between family members: disengaged, separated, connected, enmeshed. The indicator of family adaptation shows how much the system is able to adapt and change under the influence of stressors: rigid, structured, flexible, chaotic. When interpreting the results, moderate (balanced) levels of cohesion and adaptation are distinguished, which indicate the successful functioning of the family system; extreme (extremely high or low) levels are considered problematic. The methodology was adapted in Russia by Eidemiller (2006). The study used a form for families without children; it contains 20 statements describing marital relations, spending time together, especially decision-making and distribution of roles. Respondents rated each statement using the Likert 5-point scale from “almost never” (1 point) to “almost always” (5 points).

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion showed the normality of the data distribution in the sample: relative to the indicator of family adaptation Z=1.12 at р=0.15, relative to the indicator of family cohesion Z = 1.18 at р=0.11. Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.89 and 0.83, respectively.

Procedure

Transversal data slice was conducted in April-May 2020, six weeks after the beginning of strict quarantine in Ukraine due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were involved on a voluntary basis from among students and employees of universities, as well as members of their families. All contacts with the experimenter occurred online. Families received a set of forms with instructions and materials for diagnostic procedures; the organizers answered questions arising during the survey. The partners passed a pre-survey on the financial status of the family together, then each of them completed the questionnaires separately. Respondents were guaranteed the confidentiality of personal data, although it was not forbidden to discuss the content of the questions and their own answers with their spouse.

Data analysis involved a preliminary check of the internal consistency and normality of the distribution of quantitative variables. Content analysis was conducted for open questions of the questionnaire on financial behavior of spouses and other qualitative data; a series of variations was built that reflected the frequency of responses of different content for the questionnaire for studying the severity of conflicts and individual items of the SEW. In the process of analysis, sub-samples of husbands and wives were considered separately; paired Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean trends in the two dependent samples. The Pearson correlation coefficients between the measurements in the total sample, as well as separately in the gender samples, are calculated. Correlations within the family as a whole system were considered separately (two sets of similar male and female variables were measurements of one object). We used SPSS Statistics (Version 16) for calculations.

Results

Economic well-being of Ukrainian families in a lockdown situation

A survey on financial status showed that during the year preceding the pandemic in most families (regardless of income level), the spouses’ contribution to the overall financial well-being was approximately equal or the husband’s income dominates. In only five families (3.7% of the sample) a woman’s income significantly exceed that of a man. However, in 13.2% of couples women did not work and were fully dependent on their husbands.

The survey participants named a variety of ways to co-manage finances. Couples having a common budget and make decisions on large and small purchases together made up 78.7% of the sample. Despite the fact that the husband’s income dominates in the families in most cases, wives more often manage the budget: they have a decisive vote on the need for ongoing expenses or investments, while the women report to the partner about their own expenses. At the same time, 49.3% of respondents said that they did not inform partners about all their full income and expenses.

The lockdown situation had a significant impact on the income and expenses of the family; more than half of the respondents indicated significant financial losses up to a complete loss of income. Families where one or both spouses temporarily lost their jobs were forced to spend their financial savings, and in case of their absence — ask for help from friends and close relatives. At the same time, 60.3% of families indicated increased daily expenses; about a third reported cases of panic consumption: the purchase of food and medicines “in store”.

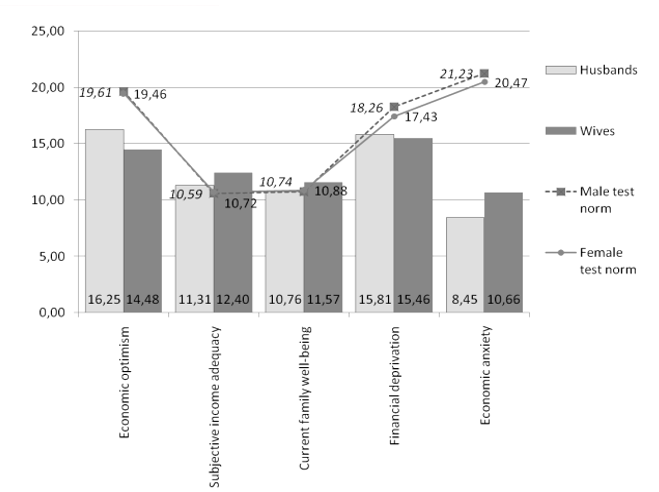

Diagnostics of subjective economic well-being showed the severity of financial stress. The overall SEW score was significantly reduced in 52.2% of respondents. The average test score in the sample was 62.58 ± 5.71 for men and 64.57 ± 8.92 for women, which is significantly different from the group test norms of the questionnaire (according to Khashchenko (2011), 80.06 for men and 78.81 for women). Analyzing the averages of individual subscales, it is noticeable that the most pronounced violations concerned, first of all, according to Khashchenko (2011). When analyzing the means of individual subscales, it is noticeable that the most pronounced violations concerned, first of all, financial deprivation and anxiety, as well as a decreased economic optimism — see Figure 1. The test norms represent a sample of 211 men (mean age 31.5 ± 9.20) and 244 women (mean age 31.5 ± 9.84) of different professions, of which 48.1% were married (Khashchenko. 2011).

Figure 1. Contrast of the Obtained Average Indicators in the Sample of Ukrainian Families with the Indicators of the Test Norms of the SEW Methodology.

None of the respondents showed low severity of economic anxiety, more than a third of participants (36%) received high scores, indicating strong concern for their financial situation due to the situation in the country, feelings of anxiety about the future, lack of funds and expressed need for increased income.

Expressed economic pessimism was diagnosed in 24.3% of respondents who negatively assessed their financial capabilities and prospects against the background of the country’s unfavorable economic future. A high level of financial deprivation was found in 20.6%; they are characterized by a feeling of apathy and hopelessness caused by negative assessments of the economic situation of their family during the survey.

All of these are signs of acute or chronic financial stress, which affects the overall decline in the level of subjective economic well-being in the sample.

With a noticeable decrease in the level of income in the sample, subjective assessments of the current well-being of the family did not significantly change, and the indicator “subjective adequacy of income” (correspondence of the size of the income to the needs and demands of the individual) even showed a tendency to increase. This led us to the assumption that in a situation of acute financial crisis, family partners consciously or instinctively reduce the level of needs (independence, self-realization, security) in order to maintain a balance of resources and a sense of subjective well-being.

Analysis of the SEW questionnaire items revealed the uncertainty of the financial future of the respondents. 69.9% indicated that their standard of living over the past year has declined significantly, 89.0% do not expect an improvement in the economic situation in the country in the near future. But at the same time, the respondents did not feel a sense of hopelessness and believed that, with all their abilities and efforts, they would be able to provide strong wealth in the family (72.1%).

Subjects and severity of financial conflicts

The survey allowed us to clarify the phenomenology of financially-caused conflicts and make a list of common problems that couples face — see Table 1. Financial issues rarely cause positive emotions when discussed in families — this is mainly related to the discussion of long-term goals, major purchases, holidays and expenses for children (not more than in 15-20% of families). The most stressful and frequently discussed issue was the lack of funds for certain current needs of partners. Wives report this problem more often than husbands (42.6% in the female sample).

Table 1 shows that the frequency of discussion and the acuteness (soreness, tension) of different financial topics do not coincide. For example, family current expenses are constantly discussed and are emotionally neutral. Topics such as debts are rarely discussed, but cause extremely negative emotions. Discussion of differences in personal habits is usually accompanied by criticism of the partner’s financial behavior (parsimony or squander), and is perceived negatively.

Table 1.

Frequency of Discussion of Financial Issues by Partners and the Related Stress Tension (Means, Standard Deviations and Frequency of Answers in a Sample of 136 Families)

.png)

The findings that the spouses very rarely talk with each other about long-term financial goals and risks, and also avoid discussions of leadership in family budget management — more than 50% of respondents chose the answer “never” — cause anxiety.

Husbands, in comparison with wives, are less likely to declare their own material needs and desires. Wives initiate discussions on economic topics more often (average score 1.77 compared to 1.35; paired t (136) = -2.61 at p = 0.011). The overall assessment of stressful tension when discussing financial issues between men and women does not significantly differ (average score is -0.47 and -0.41; paired t (136) = -1.17 at p = 0.243).

According to the results of correlation analysis, the frequency of discussion of financial issues by spouses directly and strongly correlates with indicators of family cohesion and adaptability (r=0.206, r=0.230 at p≤0.01). No significant correlations were found between the level of income and the frequency/severity of the discussion of financial problems, which does not exclude nonlinear correlations.

Coping behavior strategies during lockdown

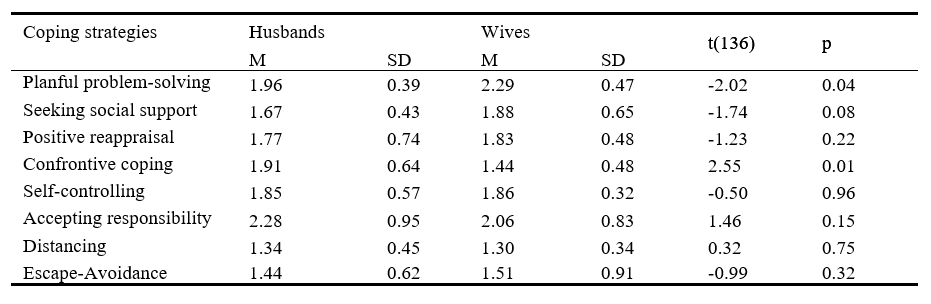

Diagnosis of spouses coping behavior during in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic recorded a high activity aimed at coping with a stressful situation. Answering the WCQ questions, the respondents almost did not choose the answer option “never”, noting the greater or lesser frequency of using different overcoming options. That is, almost the entire range of available coping strategies was used. Table 2 shows average trends and gender differences in the samples.

Table 2.

Results of Comparative Analysis of Coping Strategies for Couples During Lockdown 2020 (N=136, Paired Student’s t-test)

Most husbands were inclined to the strategy of taking responsibility (which includes an element of self-blaming) — it turned out to be the leading among 71.3% of respondents; consistent problem solving and confrontive coping were also often used. For women, as for men, the leading strategies were a consistent solution to the problem and acceptance of responsibility (an average score of more than 2 points indicates the choice of answers “sometimes” and “often”). Women are more likely to prefer planning than men, and men are active and persistent, although somewhat impulsive.

In a situation of financial stress, self-control strategy was of great importance — restraining one’s own feelings and emotions, including efforts aimed at “so that others would not know how bad things were.” 61.8% of men and 52.9% of women, when answering this question, chose the answer “often”. We assume that partners try to hide their own financial problems and related negative experiences — not only from outsiders, but also from each other.

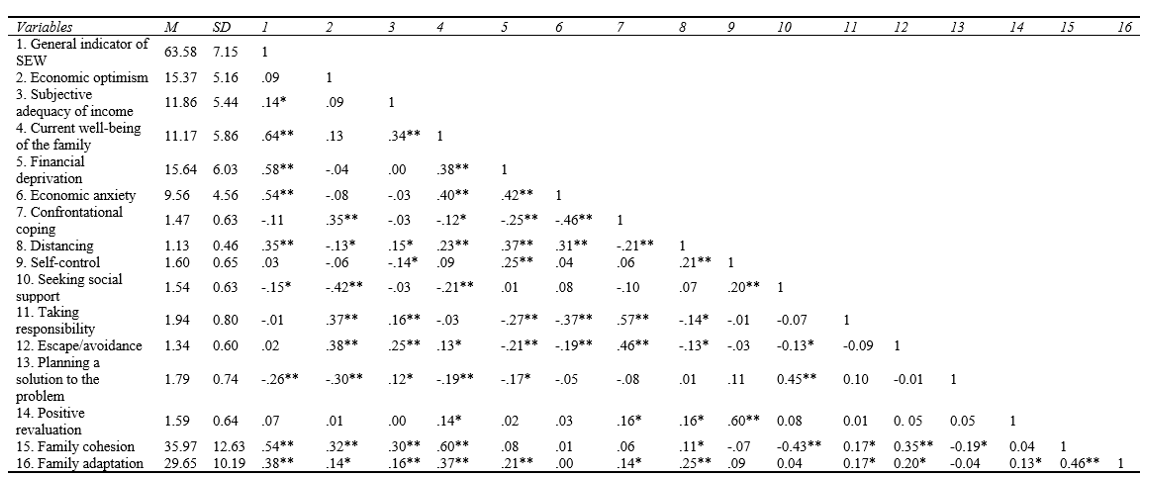

The frequency of choice of certain coping strategies is closely related to the components of SEW and indicators of family functioning, which opens up a wide space for analysis of these variables as possible predictors of financial well-being — Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables (N=272)

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Note: indicators “Economic anxiety” and “Financial deprivation” are interpreted on the inverse scale, that is high scores indicate financial tranquility and the appropriate level of satisfaction of material needs.

In particular, awareness of financial stress is directly related to reluctance to distancing, it is able to actualize confrontational coping, a person’s thoughts about his/her own role in the problem or an attempt to avoid stressors by immersing themselves in fantasy (or, conversely, people with such behavioral patterns experience anxiety more acutely).

All components of SEW, except for economic anxiety, are directly correlated with the severity of family adaptation, the closest correlations are obtained in relation to the current well-being of the family. In other words, economically prosperous people have a high ability to change flexibly and adapt to the effects of stressors in family relationships.

Interaction of gender roles and coping strategies within the family

A comparative analysis showed that the component composition of SEW was significantly different in men and women. Wives turned out to be more inclined to economic anxiety, reflecting financial stress and other negative emotions in connection with financial problems, perceived need for money (paired t (136) = -4.35 at p=0.000). Husbands showed a more pronounced economic optimism — a positive assessment of the external and internal conditions for the growth of material well-being in the future (paired t (136) = 2.69 at p=0.008). This shows the complementarity of marital roles.

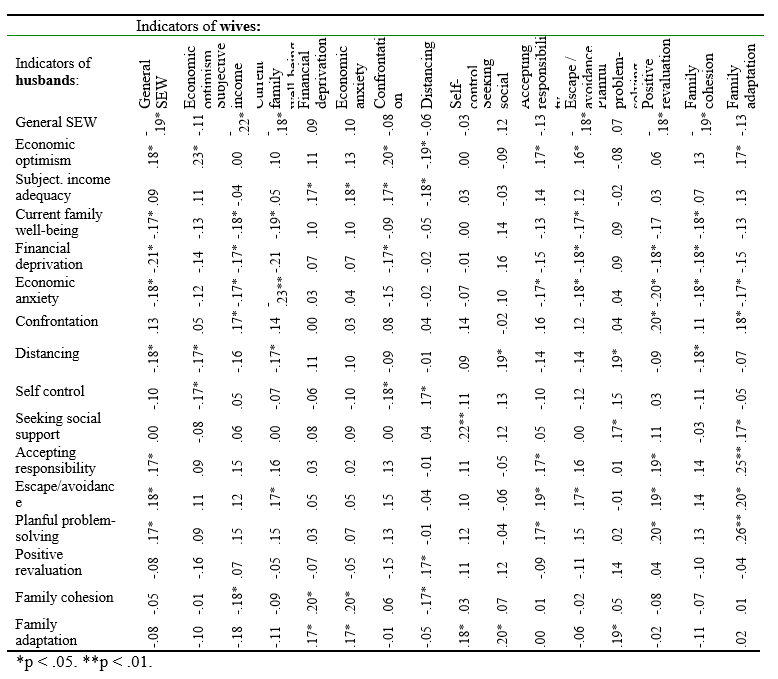

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the interdependence of the experience and overcoming the financial crisis in married couples (Table 4).Table 4.

Correlation in the family system: between Diagnostic Indicators of Wives and Husbands (N=136)

Presentation of the results of correlation analysis is unusual at first glance, because the object of consideration are not individuals but families. Each case contains two sets of diagnostic variables: for the wife and for the husband. In this case, the data of partners are considered as structural elements of a single two-component system — dyads. We are interested in the area of the correlation matrix that shows the “cross” correlations of the same indicators of partners of different sexes. The resulting relationships of variables reflect the internal mechanisms of functioning of the family.

First of all, we draw attention to the fact that the overall assessment of the SEW in husbands and wives are negatively correlated (p≤0.05). An analysis of the correlations between the components of the SEW allows us to clarify this relationship: if the husband does not declare the existing financial stress and deprivation (and probably does not take appropriate active actions), the overall well-being of the wives significantly reduces. Ignoring really adverse financial circumstances (distancing, reducing the significance of the problem) by husbands can be a source of family conflict. At the same time, the increase in economic optimism of husbands has a beneficial effect on the SEW of wives (p≤0.05). The level of economic optimism of spouses is closely interconnected (p≤0.01), which is due to joint plans, identically positive or negative views on the future.

It is interesting that the wife’s satisfaction with the family’s well-being and the subjective adequacy of the family’s income to her needs is accompanied by a manifestation of the husband’s financial stress and a decrease in his SEW, as well as by the intensification of the partner’s confrontational coping. A high subjective assessment of family income by husbands is interconnected with the absence of financial stress for wives (p≤0.05). All this indicates that the economic well-being of women in modern Ukrainian families is a matter for husbands and a source of stress for them.

Numerous correlations were found between coping indicators for husbands and wives, which specify complementary or coherent dependencies — see Table 4. The indicators “escape from problems” and “taking responsibility” positively correlate — as a rule, spouses jointly implement these strategies (p≤0.05). Negative correlations between the severity of coping strategies in a married couple indicate complementary behavior. For example, avoiding solving problems of one spouse is offset by increased responsibility of the partner.

The husband’s intense experience of economic stress correlates with wife’s coping strategies. Most wives try to support their partner in overcoming financial problems, which is manifested in inclusion, sharing responsibility and willingness to solve the problem together, as well as efforts to find the positive aspects of the situation.

Distancing from the problem of one of the partners reduces the economic optimism of the other partner. Problem-oriented husband coping improves the SEW of wives, but does not correlate with the partner’s similar behavior. That is, when the husband takes on the solution of problems, the wife “relaxes.” If the wife takes on solving the financial problems of the family, this, on the contrary, aggravates the feeling of financial stress of the husband and stimulates two opposite trends: on the one hand, the man seeks to actively engage in solving the problem, and on the other, he can choose avoidance strategy.

Experiencing financial stress by husbands and wives differently affects the quality of family adaptation. The calmer the wife is in terms of finance, the higher is the assessment of family cohesion by her husband. Concerns of husbands about the family’s financial condition contribute to increased cohesion, causing responses of wives in the form of support and inclusion. In other words, a cohesive and adapted family implies a financially reassured, well-off wife and a financially stressed husband, which is apparently associated with the distribution of socio-economic and gender roles.

It is important to note that coping focused on the search for social support extends to relationships within the couple and affects the level of family adaptation. If the wife accepts responsibility for the emergence and resolution of problems, including financial ones, this significantly increases the husband’s economic optimism (p≤0.05).

The obtained results fill the idea of the systemic unity of the family with concrete content. In particular, in a situation of financial stress, people react differently to difficulties and can choose certain coping strategies based on the characteristics of the experiences and reactions of their partners.Discussion

The study was designed to answer the question of how the lockdown situation has affected the economic well-being of Ukrainian families and how coping strategies and communication between men and women about finances are related to the level of their SEB. Lockdown introduced because of the spread of COVID-19 has significantly worsened the psychological and economic well-being of Ukrainian families. Financial stress significantly reduced the SEW of partners, reflected in the functioning of the family and the quality of family relations. Coping with it is complicated by the spouses’ failure to openly and emotionally neutrally discuss economic problems. Although partners are stressed when speaking on financial topics, this should not impede such conversations. McWhinney (2019) warns: “Like common health problems, financial anxieties — if not addressed — can become far bigger problems with much more difficult solutions.” Recent studies show that even negative emotions do not harm the relationship of spouses and perform potentially adaptive functions (Rohr et al, 2019).

The obtained statistics of coping behavior adult Ukrainians differs from previous results of researchers (Kornienko, 2018); our sample is characterized by relatively rare selection of strategies of positive revaluation and escape. In addition, the results do not coincide with the prevailing opinion about the gender differences in coping styles: the tendency of women to seek social support, and men — to self-control and planning (American Psychological Association, 2012; Kryukova, 2010). The obtained data cannot be considered a refutation of previously published results, since the characteristics of the stressor determine the response to stress. Although there is a general idea of the effectiveness of a particular strategy, a specific case always depends on the type of threat, expectation, controllability, etc. Coping productivity changes as the situation evolves, so the variety of scenarios contributes to better adaptability (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; MacCrae & Costa, 1986).

The results reflect the peculiarities of stress during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic: strong, unexpected, uncontrolled, spanning many areas of life. In addition to financial difficulties, stress was accompanied by forced social isolation, a change in habits and rules of behavior, fear for the life of oneself and loved ones, and the uncertainty of the future. The fact that the whole society faced a problem from which no one knew a way out can explain the decreased seeking support.

However, real income losses are not decisive in the emergence of a subjective experience of economic distress. Psychological factors turned out to be important elements at the time of the breaking out of the pandemic. A temporary decrease in the level of needs helped to achieve the subjective adequacy of income. An optimistic outlook on the future reduced the negative impact of the crisis.

The results confirmed that the strategies for overcoming and communicating between men and women on financial issues are strongly related to their SEW level. As correlation analysis does not solve the problem of causation, the obtained coefficients may reflect the influence of SEW on the choice of economic behavior strategies or, conversely, the SEW determined by the ability to effectively solve financial problems. Earlier, Khashchenko (2012) established that the type of SEW determines the economic activity of a person: the choice of long-term and relevant goals, life support strategy, as well as the degree of responsibility for one’s own well-being. Studies by Plotnikov and Shperlin (2014) confirmed that SEW is associated with the choice of destructive or effective strategies of economic behavior. Kuzmenkova and Kuskov (2019) found out the psychological defense and coping strategies inherent in people with different psycho-economic types. Our study complements the knowledge about the destructive effect of distancing on the relationship of a couple during a financial crisis.

We consider the data obtained extremely important, because it demonstrates how the subjective economic well-being of men and women correlates with the coping strategies of their family partners. We found that the subjective assessment of economic well-being and the degree of financial deprivation of one partner most often does not coincide with a similar perception of the other partner. The wife’s high material needs and expectations act as an additional stressor for the husband, who assumes the social role of the family’s breadwinner. The severity of financial stress in the wife is associated with a deterioration in the quality of family relationships, which affects the husband’s activation and choice of coping strategies. The severity of financial stress in a husband is directly related to the activation of coping behavior of wives and increased family cohesion (up to dependence). In a situation of financial crisis, wives expect husbands to have an adequate assessment of family problems, awareness of stress, involvement and activity in overcoming it. The husband’s SEW and his choice of ways to overcome difficulties depend on how much the wife shares responsibility for the financial condition of the family and on the copings she uses. Both the escape of wives from a decision and their acceptance of responsibility in a situation of financial crisis increases the level of economic anxiety of husbands.

The results obtained raise an important issue about the general inconsistency of social roles in the modern family, where the responsibilities for securing and controlling finances are debatable. The traditional distribution of gender roles is based on the fact that men and women have different sources of stress and different strategies to overcome them. Women likely to need support, the manifestation of emotions and the desire to share them with others; the male model of behavior includes the desire to be physically and intellectually active, not to show signs of weakness, not to discuss their problems with other people (Kornіenko, 2018). We see that such stereotypes apply to the financial behavior of Ukrainian families. Burn (1996) explained that men often choose unconstructive coping, feeling their failure as the breadwinner of the family. In the event of loss of earnings, they give up and show helplessness more often than women.

Zmanovskaya (2020) notes the blurring of personal boundaries in families: as a result of the “pathogenic merge”, they infect each other with excessive anxiety, project their problems onto the partner and delegate him/her responsibility for their own well-being. Our results partially confirm the desire of partners to symbiotic relationships during the crisis.

It is known that the leveling of sex and gender differences in modern society manifested in a mixture of marital roles: partners do not understand what household and economic roles they should play. Economically independent women compete with spouses and show less tolerance for their shortcomings. A real financial power in families often belongs to wives, but they exercise it indirectly, masking their influence. At the same time, a hidden conflict develops between social stereotypes and the real behavior of partners: “Women behave extremely contradictory: demanding husband’s tenderness and obedience in everyday situations, expect high activity in sex and in solving family’s financial issues. Men, on the other hand, expect their wives to recognize their superiority and at the same time easily shift the solution of financial and other complex issues to her» (Zmanovskaya, 2020).

The obtained results represent the family as an integrated open system in which all members share the influence of external factors and mutually influence each other. Previous studies of hereditary coping noted the possible reactions of partners in a situation of joint coping: stressful communication, positive coping of one partner aimed at supporting the other partner (empathy, active participation, etc.); positive joint coping (collective efforts); negative reactions of one of the partners (protective buffering, hostility or ambivalence); negative joint coping, disengaged avoidance (Falconier & Kuhn, 2019). We found all types of reactions described in our study.

It is known that the dynamics of the choice of coping styles in the family develops from individual to joint coping efforts (Kuftyak, 2012). Positive joint coping of spouses increases satisfaction with marriage: it can help reduce emotional tension, settle conflicts, and constructively resolve difficult life situations (Koroleva & Kryukova, 2016). Dyadic coping is supplemented and complicated by the individual reactions of partners, each having their own perception of stress (Hilpert et al., 2018; Shypova, 2020). Relations between spouses during times of financial stress can be affected by the effect of buffering. According to longitudinal studies, sharing stress when receiving support from a partner significantly increases satisfaction with relationships (Rusu et al., 2020); support is especially significant for women (Hilpert et al., 2018).

Lack of finance is undoubtedly an important factor in the formation of family relations, but it is not the main or only one. Most likely, all previously accumulated problems and disagreements sharply manifest themselves in this situation. The financial crisis can both improve and worsen the relations of partners. Difficulties can have positive results: stimulate life changes, contribute to strengthening the family and personal development. The protection from the negative effects of financial stress is supported by marital relations, thanks to which the couple feels capable of solving problems together, as well as a sense of personal competence and the ability to manage the economic circumstances of their lives.

Conclusions

The family responds to financial stress as a single flexible social system that seeks to protect its integrity. Partner coping strategies are determined by gender roles: because of the generally accepted role of the “breadwinner,” husbands are more sensitive to stress, and women tend to merge with their partners to dependence on each other. Coping behavior is influenced by individual attitudes, perception of stress and the subjective well-being of each family member. The efforts of partners can be congruent, reinforcing each other and complementary, compensating for each other’s shortcomings. Joint co-ownership determines the adaptive functioning of the family system.

Limitations of Results

The described patterns reflect the peculiarities of financial consciousness and coping behavior of Ukrainian urban families during the period of mass socio-economic crisis. The study was a one-step slice at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was long and wavy in nature. The corresponding dynamics continues to be studied, so the described conclusions describe the first stage of adaptation of partners to unexpected and relatively short-term stress. The above results do not take into account the difference in family income, this analysis will be published later.