DOI: https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2021.41.05.19

Teacher education program supporting critical thinking skills: a case of primary school teachers

Eleştirel Düşünme Becerilerini Destekleyen Öğretmen Yetiştirme Programı: Bir Sınıf Öğretmeni Örneği

Abstract

This quantitative study investigates the needs of primary school teachers for better Teacher Education Program supporting critical thinking skills. The study was carried out at four different public and private primary and secondary schools in Erbil, Iraq, during the 2019–2020 academic year, when the COVID-19 pandemic caused the suspensión of classes and the closure of educational centers. An online survey was conducted with 48 physics, mathematics, Kurdish, and social science teachers to gather data regarding how teachers support students’ critical thinking skills in the classroom. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and revealed that teachers were inefficient in encouraging students to use critical thinking skills in the classroom. The findings indicated that teachers require training to improve skills such as open-mindedness, asking high-level questions, questioning information accuracy and reliability, and searching for causes or evidence. Hence, the study proposes a teacher education program to supporting critical thinking.

Keywords: Critical thinking, teacher behaviors, needs analysis, teacher education, teacher education program.

Öz

Bu nicel çalışma, ilkokul öğretmenlerinin eleştirel düşünme becerilerini destekleyen daha iyi Öğretmen Eğitimi Programı'na olan ihtiyaçlarını araştırmaktadır. Çalışma, COVID-19 salgının sınıfların askıya alınmasına neden olduğu 2019-2020 akademik yılında Irak, Erbil'deki dört farklı devlet ve özel ilk ve ortaokulda gerçekleştirildi.eğitim merkezlerinin kapatılması. Öğretmenlerin öğrencilerin eleştirel düşünme becerilerini sınıfta nasıl desteklediklerine ilişkin verileri toplamak için 48 fizik, matematik, Kürtçe ve sosyal bilimler öğretmeniyle çevrimiçi bir anket gerçekleştirildi. Veriler, betimsel istatistikler kullanılarak analiz edilmiş ve öğretmenlerin, öğrencileri sınıfta eleştirel düşünme becerilerini kullanmaya teşvik etmede yetersiz kaldığı ortaya çıkmıştır. Bulgular, öğretmenlerin açık fikirlilik, üst düzey sorular sorma, bilgi doğruluğunu ve güvenilirliğini sorgulama ve nedenleri veya kanıtları arama gibi becerileri geliştirmek için eğitime ihtiyaç duyduklarını göstermiştir. Bu nedenle çalışma, eleştirel düşünmeyi desteklemek için bir öğretmen eğitimi programı önermektedir.

Anahtar Sözcükler: Eleştirel düşünme, öğretmen davranışları, ihtiyaç analizi, öğretmen yetiştirme programı.

Introduction

The uncontrollable flow of information across all areas of the world has forced societies to adapt to developments and changes resulting from the technology era (Halpern, 1998; Lewis and Smith, 1993; Roschelle et al, 2000a). A growing body of literature recognizes the importance of critical thinking skills embedded in education as an essential tool in adapting to these changes and developments (Behar-Horenstein and Niu, 2011a; Feuerstein, 1999; Forawi, 2016; Furness, Cowie and Cooper, 2017; Husamah, Fatmawati and Setyawan 2018; Miri, David and Uri, 2007; Williams, 2005a). Recent developments in the field of education have led to renewed interest in critical thinking skills for the last three decades (Forawi, 2016; Furness et al, 2017; Roschelle et al, 2000a; Williams, 2005a). As a result of these studies, it was alleged that critical thinking skills is an important component that should be included in education and plays a key role of development of fundamental cognitive skills and dispositions for all individuals (Feuerstein, 1999).

Halpern (Forawi, 2016; Miri et al, 2007; Williams, 2005a) Halpern (1998) demonstrates a strong and consistent association between improvement of critical thinking skills and education. He suggests that critical thinking skills have been identified as one of the defining qualities that should be cultivated through education. Moreover, in their analysis of critical thinking skills, Lewis and Smith (1993), and Piro and Anderson (2015) reported that critical thinking is also a key mechanism in the establishment of a democratic society, culture, and the power of countries to manage global economic competition.

Unfortunately, students are not typically taught to think or learn independently, and they rarely “pick up” these skills on their own (Behar-Horenstein and Niu, 2011a; Feuerstein, 1999; Miri et al, 2007). Critical thinking is not an innate ability. Although some students may be naturally inquisitive, they require training to become systematically analytical, fair, and open-minded in their pursuit of knowledge. With these skills, students can become confident in their reasoning and apply their critical thinking ability to any content area or discipline (Szabo and Schwartz, 2011)

Teachers do not simply convey the knowledge but works with learners to instill the high-level thinking skills necessary to gain productive abilities. A large-scale longitudinal educational research study on the determinants of higher order thinking skills(Hjerm, Johansson Sevä and Werner, 2018; Toy and Ok, 2012; Wang, 2013a) concluded that teacher quality is the most important key elements of applying a wide range of dispositions in terms of developing the critical thinking skills in the schools. Those components of higher order thinking skills are needed to not just think effectively but to be knowledgeably to put that ability into practice (Setiawan et al, 2018).

Given that critically thinking individuals are among the most important educational outcomes desired by democratic and modern education systems, the necessity for teachers to have critical thinking skills is indisputable (Lorencová et al, 2019). Teachers at the primary education level play an especially active role for students who are in the most important period of their cognitive development from ages 7–12 (Hager and Kaye, 1992a). Due to the importance of behaviors in the classroom and the need to be role models for students, it is imperative to determine the training needs of teachers at this level in order to support critical thinking in the classroom.

Although many studies have been carried out in various countries(Eales-Reynolds et al, 2017; Mulyono, 2018; Roschelle et al, 2000b) regarding critical thinking among teachers, there is no study exists on teacher behaviors supporting critical thinking in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq; thus, the aim of this research is to find out whether the primary school teachers use different strategies to improve the critical thinking level of primary school children. In line with this purpose, the main research question is as follows:

What are the needs of teachers regarding the Teacher Education Program Supporting Critical Thinking?

The sub-questions are as follows:

- Do teachers adequately demonstrate behaviors that support critical thinking in the classroom?

- Do teachers who support critical thinking adequately show the following dimensions?

- Open-Mindedness (OM),

- Questioning of Accuracy/Reliability of Information (QARI)

- Reasoning regarding Causes/Evidence (RCE),

- Ability to Ask High-Level Questions (AHLQ

- Openness (O)

Literature Review

The concept of Critical Thinking (CT) has been employed in a variety of disciplines and concerns issues of logical, ethical, pedagogical, and epistemological domains (Fawkes et al, 2005)Aiming at organizing the vast amount of CT aspects, specialized foundations and centers have occasionally undertaken the mission to define, construct, assess, improve, and advance the principles and best practices of fair-minded critical thought in education and society (Mahdi, Nassar, and Almuslamani, 2020; van der Zanden et al, 2020). A considerable number of theorists have attempted to define the term CT, emphasizing various concepts, such as the ability to engage in purposeful, self-regulatory judgement (Behar-Horenstein and Niu, 2011b), the use of those cognitive skills or strategies that increase the probability of a desirable outcome (Williams, 2005b), or that waste of time between seeing something and knowing what to do about it (Wang, 2013b). According to many experts from (Halpern, 1998) Delphi Committee, CT has been acknowledged as a purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based.

(Setiawan et al, 2018) (Lunenburg, 2011) concluded in his comprehensive study that educational institutions should provide a learning environment where individuals are trained at to act as critical observers, to be defenders of democratic institutions and human rights, to contribute to their field of work, and to achieve economic success to their societies. In the same vein, (Hunaidah et al, 2018)pointed that individuals, who can question, criticize, make effective decisions, and be creative and responsible for themselves and to their societies, can be grown through a quality education.

Broadly similar points had already been made by (Gülen, 1996) who points out the different social problems of humanity such as poverty and hunger, global warming, environmental pollution, violence and harassment, terrorism, and gender inequality can only be solved with a quality education that develops students spiritually, intellectually, and physically; in other words, coping with these challenges requires substantial critical thinking. Even though critical thinking skills is not the only answer to those social problems, loose, biased or misinformed thinking will undoubtedly weaken society's potential to become more productive and humane. Thus, promoting critical thinking practices and skills in societies will help everyone effectively address the challenges we face as a nation. The latest literature on critical thinking emphasizes the important roles of schools and teacher training programs in achieving this mission.

Critical thinking should therefore be treated as an integral part of education rather than as an optional component of the teaching process (Lévesque, 2008). Given the number of students who go through our schools, teachers could eventually affect the critical thinking skills of an entire society. According to the standards of the (Anon 2011), teachers should be proficient in "instructional strategies for students' development of critical thinking, problem solving and performance skills" (p. 20). However, it is unlikely that teachers will promote students' critical thinking unless teachers themselves become skilled critical thinkers.

Studies over the past two decades have provided a common understanding of the characteristics of a critical thinker. Researchers have agreed that critical thinking shapes a whole set of skills, tendencies, and habits to develop critical thinkers (Pithers and Soden, 2000). According to (Szabo and Schwartz, 2011) thinking is a skill that can be developed through education because it is a basic skill of human beings. (Furness et al, 2017)demonstrated that the teacher is the basic element facilitating thinking and learning in a classroom environment, and teachers—as central role models for students—should show case with their own behaviors the skills they want students to acquire(Piro and Anderson, 2015). (Ford and Yore, 2012) argued that teachers’ behaviors are more influential in the development of critical thinking than direct instruction of critical thinking. (van der Zanden et al, 2020) stated that teachers must be supported with their continuous professional development in terms of critical thinking behaviors and agreed that teachers can only set an example for students to be critical thinkers by being critical thinkers themselves.

Several lines of studies suggested that (Eales-Reynolds et al, 2017; Muskita, Subali and Djukri, 2020; Plotnikova and Strukov, 2019) critical thinking is a product, a level reached by the thinking that a natural way to interact with the ideas and information. (Howard, 2003a)development and learning are in constant interaction which is achieved assimilation and immediate adaptation. (Roschelle et al, 2000b) conclude that children construct mental structures that are generated by the internalization of actions with objects. By assimilation a correlate object existing scheme and by adapting changes its schema as the object. Discovery and action on new working process of assimilation and accommodation, and understanding occurs only when these processes are in balance. The child is trying to find meaning to the events and the world around him, and the adult has the task of creating opportunities for research and exploration, to provide emotional support, security and encourage knowledge. Socio-cultural learning theory of Lev Vygotsky is the central idea of proximal development that you need to identify the immediate vicinity of the current development. In the current development, the children independently solve problem situations, the zone of proximal development - work tasks and action is complicated because it requires action or knowledge which assimilated. With a little help from an adult / teacher, the child gets to solve the problem. Together, these studies indicate that constructivist theories focus on cognitive development, harnessing the potential hereditary by "building" the right environment Children are encouraged to use their physical and intellectual capacities to actively interact with the environment and act on it.

Many recent studies (Behar-Horenstein and Niu, 2011a; Miri et al, 2007; Williams, 2005a)show that teaching behaviors which develop critical thinking skills were found rare in primary schools. This was a surprising finding, given that the courses in teacher education were an introduction to a profession that values critical inquiry. (Howard, 2003a)reported in his research that teacher education programs provide many courses that students engaged in much activity which rarely included critical inquiry

For the last three decades research (Bundu, Ahmad, and Muhajir, 2018; Hager, 2003; Kong, 2014) has investigated how teachers and their behaviors effected student’s success and their behaviors in the classroom and in the social life. Several investigations of critical thinking(Elyas and Al-Zahrani, 2019; Kong, 2014; Mulnix, 2012) have identified teachers, specifically primary school teachers, are expected to be critical thinkers, or able to teach critical thinking skills so that they can improve their students’ higher order thinking level. The findings of Erikson and Erikson’s, (2019) reported that teachers with a high level of critical thinking often teach critical thinking to their students through various teaching methods, changing their learning activities differently, as well as their higher-level thinking skills. It has also been observed that the application skills have increased as well.

Ennis (2018) argues that although the curriculum of a primary school was design to influence the teachers to focus on subject-matter content when teaching, they can develop the critical thinking skills of their students by generalizing their abilities. If the teachers have critical thinking skills, even though they are offered little help to encompass the critical thinking, they can achieve the notion of higher order thinking in their classrooms (Dekker, 2020; Huber and Kuncel, 2016). Teachers can develop a variety of clear, accurate presentations and representations of concepts, using alternative explanations to assist students' understanding and presenting diverse perspectives to encourage critical thinking. The primary school teachers can also use multiple teaching and learning strategies to engage students in active learning opportunities that promote the development of critical thinking, problem solving, and performance capabilities and that help students assume responsibility for identifying and using learning resources. Taken together, these studies support the notion that primary school teachers need to use supporting critical thinking skills so that they can sharpen their students’ critical thinking skills.Methodology

This section presents information about the research model, study group, data collection tools, data collection and analysis.

Research Model

Different researchers have investigated critical thinking in a variety of ways. Since the purpose of this study is to describe an existing situation, namely the educational needs of primary school teachers in supporting critical thinking, a survey model based on a quantitative research paradigm was used. The survey model is a research model that allows the researcher to describe a past or existing situation of the research subject without trying to change or affect it (Tashakkori and Creswell, 2007).

Participants

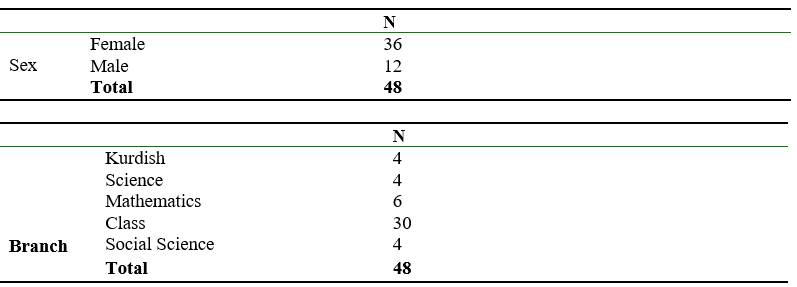

The participants of the study consisted of 48 teachers working in public and private primary schools in Erbil, Iraq. The participant teachers have taught Kurdish, Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science, and they participated voluntarily in the study. The demographic information of the participants is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Teachers in the Research Group

As seen in Table 1, most participants in the study were female teachers. Most participants were class teachers, while the rest were subject teachers (Kurdish, Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science).

Instruments

The researcher conducting the monitoring study prioritized observing and documenting the data properly during collection. The most important feature of the observation that it provides direct access to data by examining an event, phenomenon, or behavior in a normal environment. Since an individual may behave differently if they are in an artificial situation, the necessity of observing behaviors in a natural environment is a basic premise. Observation is frequently used in needs analysis because it provides the researcher with the opportunity to focus on which opinions are most important in the program development process. As such, an observation form, which was prepared in line with the purpose of study, was chosen as the data collection tool.

The observation form was created based on the dimensions outlined in the "Teacher Behaviors Supporting Critical Thinking Inventory" (Alper, 2010). While creating the observation form, the opinions of program evaluation, and language experts were taken. Items were selected that were considered to represent the broadest scope of dimensions of critical thinking. ach statement in the observation form was categorized as "observed" or "not observed," and the answer section was scored as ‘0’ for not observe, ‘1’ for observed. In order to measure the reliability of the observation form, five teachers' lessons were observed in a public primary school (classroom teaching) and secondary school (Kurdish, social studies, classroom and science branches) from beginning to end for two lesson hours each for a total of 10 lesson hours. After making the necessary corrections to the form, expert opinion was consulted, and the observation form was finalized within the framework of the feedback received.

The observation form included the dimensions of open-mindedness (OM), questioning of accuracy/reliability of information (QARI), reasoning regarding causes/evidence (RCE), ability to ask high-level questions (AHLQ), and openness (O). The form had a total of 28 indicators for the dimensions. To observe teachers' in-class practices, two lesson hours (90 minutes total) of in-class observation were undertaken for each teacher. Classroom observations were completed for 48 teachers for a total of four weeks (20 working days).

Data Analysis

The descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, arithmetic mean and standard deviation scores) of the obtained data were calculated by transferring the numerical data of the observations to the SPSS 22 program. After the statistical analysis of the data, the results were interpreted.

Findings

This section presents the findings regarding the question, "What are the training needs of teachers regarding Teacher Education Program Supporting Critical Thinking " using the descriptive statistics of teachers' behaviors that support critical thinking and the descriptive statistics of their behaviors in all dimensions.

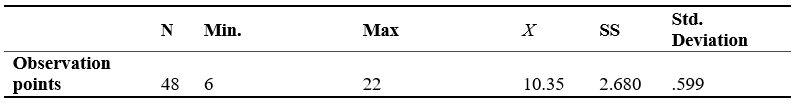

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Teachers' In-Class Observation Results.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics regarding behaviors that support critical thinking in the 24 participants’ classroom practices. As seen in the table, the average score for behaviors showing critical thinking in the classroom is 10.35. The highest obtainable score was 28, while the lowest score was 0. The lowest received point was 6 and the highest point was 22. When considering that there were 28 indicators, none of the teachers received a full score. According to these findings, participants did not show a sufficient level of behaviors supporting critical thinking.

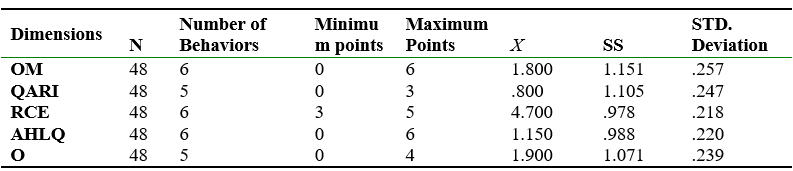

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics Regarding the Level of Teachers' Behaviors Supporting Critical Thinking in Every Sub-Dimension.

Table 3 illustrates that, on average, one third of teachers’ behaviors supported critical thinking. In other words, participants showed only one or two out of the five to six critical thinking support behaviors included in each sub-dimension. In light of the research findings, it can be concluded that participants’ classroom practices did not display a sufficient level of behaviors that support critical thinking for the dimensions of OM, QARI, RCE and AHLQ. Despite low scores in these dimensions, teachers did adequately demonstrate behaviors that support critical thinking in the ‘O’ dimension.

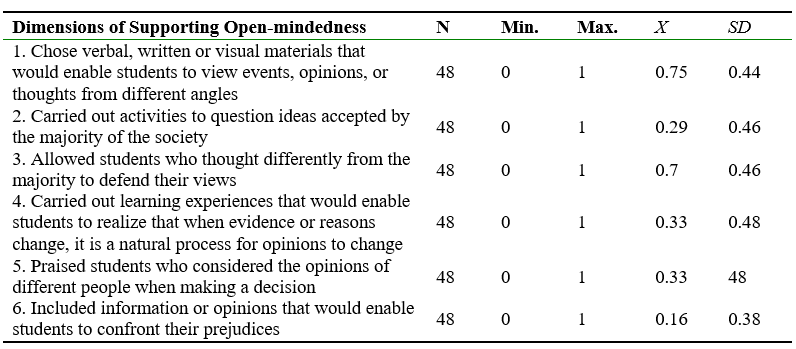

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of teachers' level of behaviors belonging to the dimension of OM.

Table 4.

OM Behaviors.

As seen in Table 4, the average scores of teachers regarding the frequency of showing behaviors in the OM dimension ranged from .75 to .16. According to these findings, the most common behavior of teachers in this dimension was "Chose verbal, written or visual materials that would enable students to see events, opinions, or thoughts from different angles" (X = .75); the least common behavior was "Included information or opinions that would enable students to face their prejudices" (= .16).

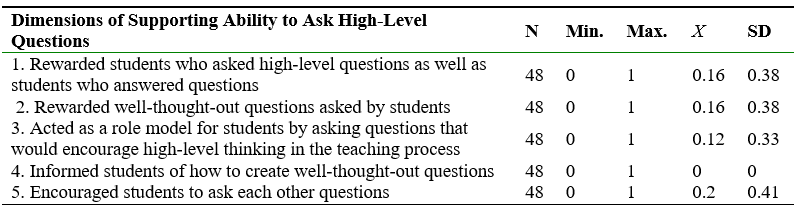

Table 5 contains descriptive statistics regarding the frequency of teachers' behaviors related to AHLQ.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics Regarding Teachers' Level of Demonstrating AHLQ Behaviors.

The average values of the frequency of teachers' behaviors in the AHLQ dimension were between 𝑋 = .20 and 𝑋 = 0. According to these scores, the most common AHLQ behavior was "Encouraging students to ask each other questions" (X ̅= .20), while the least common behavior was " Informed students of how to create well-thought-out questions " (X ̅ = 0).

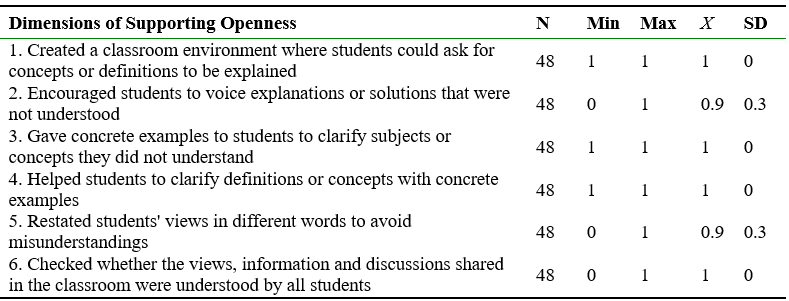

Table 6 contains descriptive statistics on the frequency of teachers' behaviors belonging to the O dimension.

Table 6.

Descriptive Statistics Regarding the Level of Teachers' O Behaviors.

As per Table 6, the average values of the frequency of teachers' behaviors in the O dimension were between 𝑋 ̅ = 1 and 𝑋 ̅ = .87. These findings show a high frequency of teachers' demonstrating behaviors to support critical thinking in the O dimension.

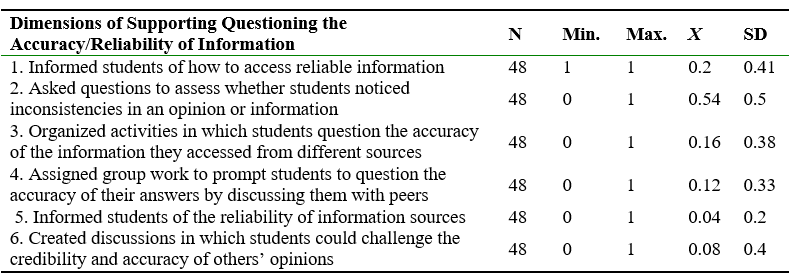

Table 7 contains descriptive statistics regarding the frequency of teachers' behaviors related to the QARI dimension.

Table 7.

Descriptive Statistics Regarding the Level of Teachers' Demonstrating the QARI Behavior.

As seen in Table 7, the average values of the frequency of teachers showing behaviors in the QARI dimension varied between .54 and .08. According to the scores, the most common behavior of teachers was "Asked questions to assess whether students noticed inconsistencies in an opinion or information" ( .54).

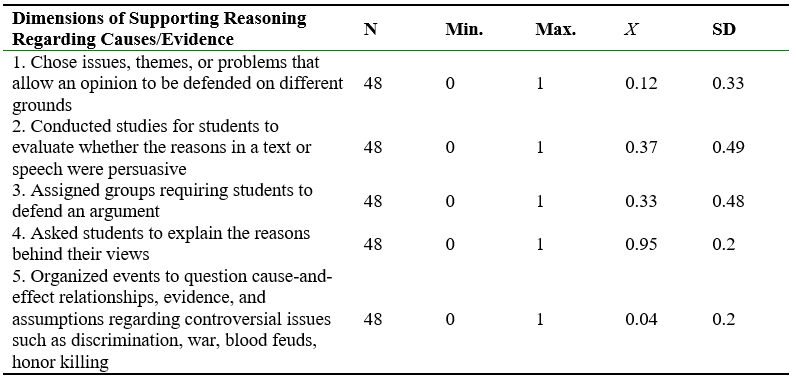

Table 8 shows descriptive statistics on the frequency of teachers' behaviors related to the RCE dimension.

Table 8.

Descriptive Statistics Regarding Teachers' Level of Demonstrating RCE Behavior.

The average values of the frequency of teachers' showing behaviors in the RCE dimension varied between .95 and .04. According to the scores, teachers’ most common behavior was "Asked students to explain the reasons behind their views" (.95).

This study examining the educational needs of primary school teachers regarding behaviors that support critical thinking revealed that teachers need training in supporting critical thinking behaviors. While critical thinking is one of the basic skills that should be acquired by students in primary education programs, teachers showed a significant deficiency in showing behaviors that support critical thinking in the classroom. Moreover, there is no material in the training programs of teacher training institutions nor an in-service training program by the Ministry of National Education in KRI that addresses behaviors teachers can adopt to support critical thinking. Studies have shown that the most important factor in teaching critical thinking is teachers (Elyas and Al-Zahrani, 2019; Kong, 2014), who include practices that develop critical thinking in their lessons produce students with greater academic achievements (Anazifa, 2016; Husamah et al, 2018; Mulnix, 2012; Piro and Anderson, 2015). The best way to train teachers in modeling behaviors that support critical thinking is to inculcate them with knowledge and awareness of those behaviors through pre-service and in-service training.

The study demonstrated that teachers are competent in demonstrating ‘O’ dimension behaviors that support critical thinking. This finding broadly supports the work other studies in this area (Howard, 2003b; Lorencová et al, 2019; Walters, 1989.)linking critical thinking and supporting behaviors of critical thinking. In this study examining primary school teachers' behaviors that support critical thinking in the classroom, was concluded that teachers generally showed behaviors that could indirectly or implicitly inhibit negative forms of supporting critical thinking behaviors. In addition, it was revealed that teachers who are responsible for curriculum design and training do not use critical thinking components (skills, tendencies, and attitudes supporting critical thinking behaviors) in their classrooms and exhibit behaviors that prevent students from critical thinking.

The study also found that teachers did not sufficiently show QARI behaviors. One of the most important characteristics of a critical thinker is "deep curiosity" (Lunenburg, 2011), and one of the teacher behaviors that supports critical thinking is that the teacher is curious about information, questions information, and encourages students to be curious. In critical thinking trends and studies (Yang and Wu, 2012), the common denominator of critical thinking for pre-service teachers is teachers' tendency to assume the accuracy of information without investigating it. This behavior was reflected in the fact that teachers received low scores in the QARI dimension.

Another result of the study revealed that teachers did not sufficiently show behaviors that support AHLQ behaviors. This finding coincides with the conclusions of previous studies that teachers mostly ask questions based on memorization and do not include questions that require high-level thinking (Eales-Reynolds et al, 2017; Hunaidah et al, 2018; Mulyono, 2018; Plotnikova and Strukov, 2019). Additionally, the study found that teachers did not show sufficient behaviors in support of the OM or RCE dimensions. Open-mindedness is one of the most distinctive features of critical thinking, and it is equally important that teachers ask questions that improve students’ higher-level thinking skills and require students to provide sufficient evidence in support of their answers.

In studies on the determinants of critical thinking in the classroom environment teacher behaviors in the classroom are among the most critical elements in supporting critical thinking among students. Based on the above-described results, which are similar to previous research findings (Bundu et al, 2018; Hager, 2003; Kong, 2014) regarding critical thinking in the classroom the imperative of training teachers in critical thinking is clear. Only teachers who have critical thinking skills that they apply in the classroom will be able to train students to think critically as well (Anderson et al, 2001; Behar-Horenstein and Niu, 2011b; Mulyono, 2018; Roschelle et al, 2000b)

Conclusions

According to the results of this study, primary school teachers need to be trained regarding OM, AHLQ, QARI, and RCE in order to support critical thinking in the classroom. Considering the role of teachers in shaping students' thinking styles, the quality of the behaviors that teachers exhibit in the classroom is of the utmost importance.

In the light of the findings, the following suggestions are made:

- A teacher training program to supporting critical thinking should be developed based on the training needs of teachers.

- This research is based on quantitative research. Future research could use a case study method based on a qualitative research paradigm to examine teachers' behaviors that support critical thinking.

- Different school types and different levels can be studied to understand teachers’ needs regarding behaviors that support critical thinking.

- This study was conducted in a single private school and within a certain period of time due to the limitations of each research.

Broader studies can be conducted to allow longer-term, more in-depth observations to be made using the participatory observation method.