Quality assurance of teaching and learning process in economic higher education under the pandemic

Забезпечення якості навчального процесу у вищій економічній освіті в умовах пандемії

Abstract

Long-lasting pandemic uncovered the new challenge of tertiary education: how to ensure the high quality of durable emergency distance learning and enable the students to master the necessary competences. The objective of this research was to test the application of the bottom-up approach to quality assurance when students, as stakeholders, are enabled to influence content and context of their learning through regular surveys. Current research represents the comparative analysis of two surveys, conducted at the end of spring semester of 2019-2020 academic year (593 respondents), and at the end of autumn semester of 2020-2021 academic year (1193 respondents) among the students of the Faculty of Economics of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, outlining the problems students faced while the emergency remote learning was conducted during the first lockdown and measuring how these problems were fixed during the second shutdown bearing in mind the results of the first survey. The methodology combined quantitative and qualitative research methods. The current research covers the study of the methods of teaching, the level of communication between learners and educators, the level of practical skills acquisition, engagement of students in the learning process during two semesters. Also it analyses the measures undertaken by the teachers and faculty management to achieve improvement in learners’ feedback during the second survey that can be considered as best practices.

Keywords:quality assurance, student centeredness, student survey, higher education, distance learning.

Анотація

Довготривала пандемія поставила новий виклик перед вищою освітою: як забезпечити високу якість довготривалого вимушеного дистанційного навчання та надати можливість студентам оволодіти необхідними компетенціями. Завданням цього дослідження було тестування підходу «знизу - вгору» до забезпечення якості, коли студенти, як стейкхолдери безпосередньо можуть впливати на зміст та умови навчання через регулярні опитування. Дане дослідження є порівняльним аналізом двох опитувань, проведених у кінці весняного семестру 2021-2020 навчального року (593 респонденти) та у кінці осіннього семестру 2020-2021 навчального року (1193 респонденти) серед студентів економічного факультету Київського національного університету імені Тараса Шевченка, які визначили проблеми, з якими стикнулись студенти під час вимушеного дистанційного навчання в період першого локдауну, та виміряли, як ці проблеми було вирішено під час другого карантину з урахуванням результатів першого опитування. Методологія дослідження поєднала кількісні та якісні методи досліджень. Дане дослідження охоплює вивчення методів викладання, рівня комунікації між студентами та викладачами, рівня набуття практичних навичок, залучення студентів до освітнього процесу протягом двох семестрів. Також воно охоплює вивчення заходів, які запровадили викладачі та адміністрація для досягнення покращення відгуків студентів під час другого опитування, які можуть бути визначені, як кращі практики.

Ключові слова:забезпечення якості, студенто-центричність, опитування студентів, вища освіта, дистанційне навчання

Introduction

In addition to the existent challenges for tertiary education: more and more increasing gap between generations, namely, educators and learners, transition from knowledge-society to skills-society, rapidly changing requirements to the prospective employees and appearance of brand-new professions, durable Covid-19 lockdown raised another problem: quality assurance of distance learning and teaching in formal education.

One of the pillars of quality assurance is meeting the needs of the stakeholders in general and of the students, in particular. Regular student surveys are a productive tool for finding out the pros and cons of the existent teaching and learning process, for outlining the areas for further development, for elaborating effective measures in order to achieve and maintain quality of learning and teaching, especially under long-lasting distance learning that is almost ‘terra incognito’ for universities in formal education.

In this regard it makes sense for traditional universities to familiarize themselves with the distance higher education institutions’ expertise in quality assurance in e-learning, for instance, studying the experience of Madrid Open University (Madrid, Spain) and Universidade Alberta (Lisbon, Portugal) (Casado-Aranda, Caeiro, Trindade, Paço, Lizcano Casas & Landeta, 2020) or to explore this new reality by probing, trying to apply traditional quality assurance tools in distance learning, measuring the performance through regular feedback from students, staff and other stakeholders.

One of the tools that distance higher education institutions use for quality assurance is students’ satisfaction questionnaire and regular surveys. Durable remote learning triggered traditionally face-to-face universities to reconsider the conventional top-down approach to decision-making process and replace it with the bottom-up approach, when students, as stakeholders, are enabled to influence educational process, content and context of learning.

Current research contains a profound analysis of how the Faculty of Economics (one of the biggest faculties) of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (one of the top universities of Ukraine) has approached the issue of quality assurance in remote learning using regular students’ surveys for identifying the benchmarks and measuring the improvement.

Theoretical Framework

E.G. Bogue (1998) outlined several approaches to quality assurance in higher education: ‘Traditional Peer Review Evaluation’ that includes such tools as: ‘accreditation’, ‘rankings and ratings’ (Bogue, 1998; Hauptman Komotar, 2020; Rybinski, 2020), ‘programme reviews’ and ‘Assessment-and-Outcomes Movement’ that is about measuring ‘results’ rather than ‘reputation’ (Bogue, 1998) and satisfaction of individual’s educational needs (Vaganova, Gilyazova, Gileva, Yarygina & Bekirova, 2020). The more advanced approach to quality assurance is Total Quality Management that is a systematic approach to quality assurance with emphasis on continuous improvement and regular feedback from the customers (students) (Seymour, 1992; Bogue, 1998). There is also one more approach to quality management: ‘accountability’ and ‘key performance indicators’ that can be ‘student performance’, ‘retention and graduation rates’, ‘job placement rates’, ‘student satisfaction rate’ and any other quantitative indicators (Grady Bogue, 1998).

Turkish researchers Kahveci T. C., Uygun Ö, Yurtsever U., & İlyas S. (2012) applied a holistic approach to defining quality assurance in higher education that touches all the spheres of tertiary sector of education, including ‘Strategic Management, Process Management and Measurement-Monitoring’.

In Europe students are considered to be an integral part of internal and external part of quality assurance in higher education (Loukkola & Zhang, 2010; Matei & Iwinska, 2016). For instance, in the United Kingdom ‘a public national survey identifying the students’ satisfaction with the quality of programmes and HEIs (Higher Education Institutions) is conducted every year’ (Matei & Iwinska, 2016, p. 36). Loukkola T. & Zhang T. (2010, p. 9, p. 24) in their global research that covered respondents from 36 European countries, including Ukraine, identified that 79.7% of students-respondents are involved in quality assurance process in HEIs through regular surveys.

Some Asian researchers (Nguyen et al., 2021, p. 631) also report on involvement of students in quality assurance processes in higher education, for instance in Vietnamese universities some of the lecturers ask their students to give them feedback on their course after it is finished through surveys, but this fact was mentioned as lecturers volunteering rather than a compulsory procedure in their HEIs, however, it was also mentioned that quality assurance units are created in Vietnamese HEIs that is an indicator of their HEIs’ sharing the global intention to ensure quality in higher education.

A comprehensive study of quality assurance in higher education in Ukraine was done by Bugrov V. at al. (2016), who analyzed the legal framework and the documents that regulate quality assurance in Ukraine in line with the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG, 2015) and studied the current for 2016 situation with quality assurance in Ukrainian universities.

Student-centeredness and active engagement of students in creating the learning and teaching process is one of the Standards for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG, 2015, p. 12), which is implemented in Ukrainian HEIs through regular student surveys. According to the research of 2016 (Bugrov et al., 2016, pp. 59, 69) that engaged respondents from 217 HEIs of Ukraine 75% of students mentioned regular participation in teaching staff quality assurance surveys, 25% - in study programmes quality assurance surveys and 5% of students told that no surveys were conducted in their HEIs.

In 2019 the procedure of study programmes accreditation in Ukraine was changed due to the requirements of and since then is conducted by the National Agency for Higher Education Quality Assurance (NAQA) ‘in accordance with the Laws of Ukraine ‘On Education’ (Law of Ukraine No. 2145-VIII, 2017) and ‘On Higher Education’ (Law of Ukraine No. 1556-VII, 2014), the Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine ‘On Creation of the National Agency for Higher Education Quality Assurance’. (Resolution No. 244, 2015), and the Order of the Ministry of Education and Science ‘On Regulations on Accreditation of Study Programmes in Higher Education’ No. 977 (2019). According to the Criterion 4 ‘Teaching and learning under the study programme’ (Order No. 977, 2019) ‘forms and methods of teaching and learning should not only lead to achieving programme learning outcomes stated in the study programme, but also meet requirements of student-centered approach’. While in line with the Criterion 8 ‘Internal quality assurance of the study programme’ (ibid.) ‘students, directly and through their representatives in student governance bodies, are engaged as partners in the process of periodic review of the study programme and in procedures related to its quality assurance’. The latter Criterion also requires appropriate reaction from the HEI to the identified drawbacks in the study programme itself or in the way of its realization (ibid.). Thus, since 2019 there is no other way for HEIs to accredit their study programmes, but to conduct regular student surveys, to gather feedback from students in particular and to make the required changes in terms of a study programme and its realization. Especially valuable feedback was received through regular student surveys under emergency remote learning caused by Covid-19 pandemic.

Ahmed A. Al-Imarah, Robin Shields & Richard Kamm (2020, p. 14) in their study on quality assurance of massive open online courses (MOOCs) in the United Kingdom higher education proved that ‘conventional methods of quality assurance are not enough for ensuring quality in online teaching and learning’. As well as the HEIs should not ‘focus their attention only on technical requirements ignoring academic quality’ (Al-Imarah et al., 2020, p. 2), when approaching quality assurance of remote learning. The research on quality assurance dimensions for e-learning institutions in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries (Anwar, Sohail & Al Reyaysa, 2020) uncovered that holistic and multidimensional approach (Zuhairi, Raymundo & Mir, 2020) should be used for quality assurance in e-learning, including ‘dimensions of accreditation, assessment, accountability and benchmarking’. In Saudi Arabia ‘universities control the quality of the teaching process through monitoring students’ performance and academic achievement during Covid-19 distance learning’ (Bingimlas, 2021).

Methodology

Current research represents the comparative analysis of two surveys, conducted at the end of spring semester of 2019-2020 academic year (593 respondents) – Survey 1, and at the end of autumn semester of 2020-2021 academic year (1193 respondents) – Survey 2, among the students of the Faculty of Economics of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. The purpose of Survey 1 was to outline the problems students faced during the emergency remote learning during the first lockdown, whereas, the purpose of Survey 2 was to measure how these problems were fixed during the second shutdown bearing in mind the results of Survey 1.

Profile of Survey 1:

- 593 respondents of the Faculty of Economics of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (25.61% of total amount (2316) of students enrolled at the faculty);

- 83.1% of respondents – Bachelor’s Degree students (31% - 1st-year students, 20.4% - 2nd-year students, 22.4% - 3rd –year students, 9.3% - 4th –year students), 16.9% of respondents – Master’s Degree students (12% - 1st year of study, 4.9% - 2nd year of study);

- Gender distribution of the respondents: female – 68.6%. male – 31.4%

Profile of Survey 2:

- 1193 respondents of the Faculty of Economics of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (51.51% of total amount (2316) of students enrolled at the faculty);

- 85.3% of respondents – Bachelor’s Degree students (34.5% - 1st-year students, 23.6% - 2nd-year students, 14.2% - 3rd –year students, 13% - 4th –year students), 14.7% of respondents – Master’s Degree students (6.4% - 1st year of study, 8.3% - 2nd year of study);

- Gender distribution of the respondents: female – 66.9%. male – 33.1%

As it can be judged from the profiles the amount of the respondents participated in Survey 2 doubled compared to Survey 1. The reasons for this are as follows: during spring semester the 4th-year students had their internship at the public and private companies, thus their response was pretty low, 2nd-year students of Master’s Degree programme during spring semester were polishing their diploma projects, also the majority of them are employed already, so they felt more reluctant to invest their time and efforts in the survey completion. As for the rest of the students, it should be mentioned that the overall level of response during Survey 2 was much higher, because the students have noticed real improvements in terms of their concerns they expressed during Survey 1.

Both surveys were combinations of quantitative and qualitative researches. In its quantitative part both surveys contained the same set of statements, which respondents were expected to agree or disagree with:

- The material delivered by the lecturers was sufficient for you to understand the topics.

Highly agree / agree / fairly agree / disagree

- Lecturers used innovative (productive) methods of teaching and learning.

Highly agree / agree / fairly agree / disagree

- You were engaged in discussions on different issues during the lectures.

Highly agree / agree / fairly agree / disagree

- You can practically apply knowledge you gained at the lectures.

Highly agree / agree / fairly agree / disagree

- Evaluate the difficulty of assessment tasks.

High, medium, low

- You were informed about the form of summative assessment and assessment criteria far in advance and had enough time to get prepared.

Highly agree / agree / fairly agree / disagree

- Methods of teaching and learning were in line with the principles of academic freedom.

Agree / disagree / difficult to say

- What is the percentage of the classes you joined / attended?

Between 60% - 100% / between 30% - 60% / below 30%

Qualitative part of the surveys had only one question: outline the problems you faced during the distance learning. Thus, the current research covers the study of the methods of teaching, the level of communication between learners and educators, the level of practical skills acquisition, engagement of students in the learning process during two semesters. In this paper we also analysed what processes led to the improvement of the results in Survey 2 compared to Survey 1, which can be considered as the best practices.

Results and Discussion

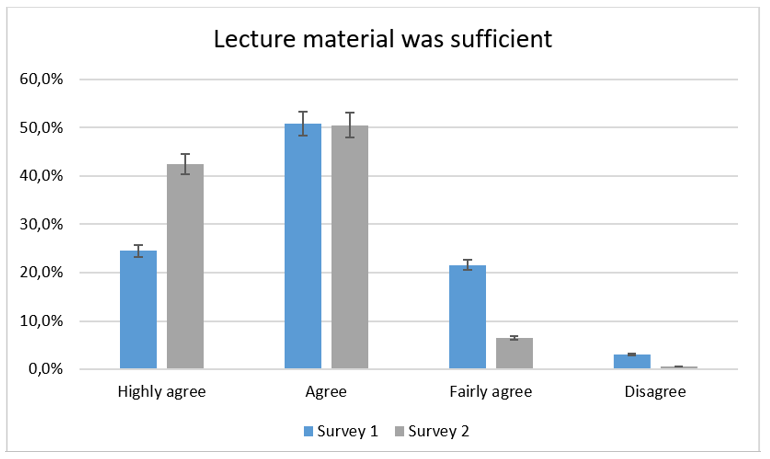

Survey 2 demonstrated that compared to Survey 1 students’ satisfaction with the sufficiency of lecture materials for their understanding of the topic raised from 75.3% (highly agree and agree) to 92.9% (highly agree and agree), whereas, the amount of respondents who fairly agreed with the statement about sufficiency of lecture materials decreased by 15.1%. Moreover, the number of respondents who were not satisfied with the volume and quality of lecture materials declined from 3.1% to 0.6%. As it can be judged from Figure 1 the situation with content of distance learning has dramatically improved. The reason for this was the lecturers have adjusted their lecture material for distance learning during summer, relying upon the feedback of students they gave personally to the lecturers or in Survey 1.

Figure 1.The material delivered by the lecturers was sufficient for you to understand the topics. Source: own.

Using of innovative teaching and learning methods according to the results of Survey 1 was quite high – 75.9% (highly agree and agree), but professional trainings the lecturers got on remote learning tools and methods allowed to increase this indicator to 84.2% (highly agree and agree in Survey 2). As it can be seen from Figure 2 the level of those who fairy agreed or disagreed with the statement that lecturers used innovative methods of teaching and learning plummeted from 24.1% to 15.8%.

methods of teaching and learning.png)

Figure 2. Lecturers used innovative (productive) methods of teaching and learning. Source: own.

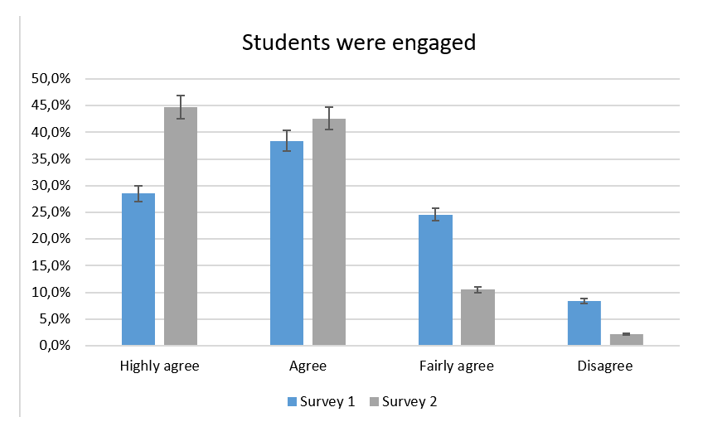

Engagement of students during the online lectures significantly grew from 66.9% (highly agree and agree – Survey 1) to 87.3 (highly agree and agree – Survey 2). At the same time the amount of those who considered themselves fairly engaged or not engaged dropped from 33% (Survey 1) to 12.7% (Survey 2). Such a sharp change happened due to the enhanced expertise of the lecturers on adjusting case studies to remote classroom, using wider variety of up-to-date online tools and platforms, applying student-centered approach in distance learning. The results can be seen on Figure 3.

Figure 3. Engagement of students in discussions on different issues during the lectures. Source: own.

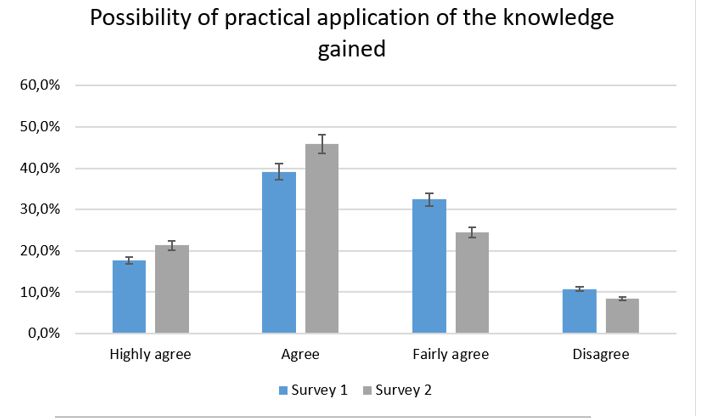

A moderate improvement can be witnessed in terms of the students’ evaluation of the perspectives of practical application of the gained during the learning knowledge. The indicators demonstrated a slight increase among those who agreed and highly agreed that they gained practical knowledge during Survey 1 (56.8%) and during Survey 2 (67.1) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Prospect of practical application of knowledge students gained at the lectures. Source: own.

The discussion here might arise in terms of how justified are the answers of the pre-service students. To our opinion, the 1st –year, the 2nd –year students and those senior students, who are not working full-time or at least part-time, can only approximately speculate how beneficial and practical are knowledge they are gaining now at university.

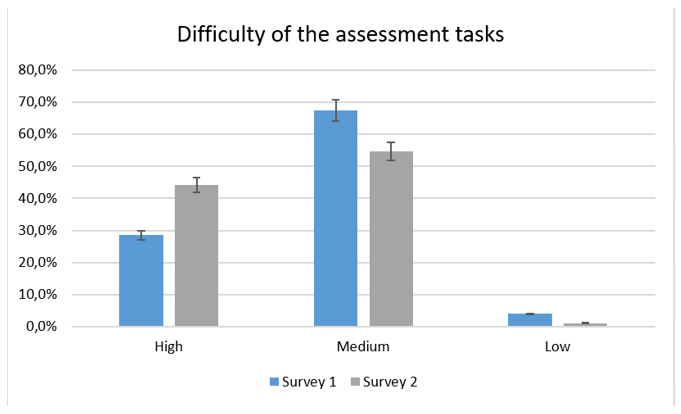

Assessment in remote learning is one of the most controversial things. Since learning is moved online, the lecturers are trying to find the new approaches to assessment in order to make it transparent and objective. Figure 5 demonstrates students’ evaluation of the assessment tasks.

Figure 5. Difficulty of assessment tasks. Source: own.

As it is seen from Survey 1 the level of difficulty of assessment tasks at the Faculty is traditionally between high (28.5%) and medium (67.5%). But Survey 2 showed a quite huge shift of the assessment tasks to higher level of difficulty: 44.2% of respondents noted them as of high difficulty and 54.7% of respondents considered these tasks as of medium difficulty. The percentage of low difficulty assessment tasks fell from 4% to 1.1%. The reason for this change seems to be quite obvious: online summative assessment leaves much room for cheating and undermining academic integrity, therefore, the lecturers have to look for new approaches to assessment, namely, to refuse from traditional tests and turn to case studies and creative tasks, so-called ‘open-coursebook’ assessment tasks, when students can use any resources for performing the task, because nowhere can they find the right or ready-made answers. By the way, this fact also contributed to the increase of the number of students, who consider that they will be able to practically apply the received knowledge.

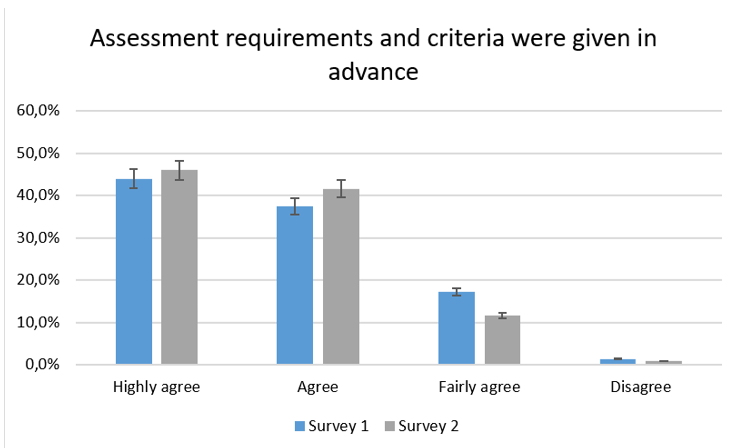

Assessment is an important factor for quality assurance, that is why we also measured whether the students were informed about the form of summative assessment and assessment criteria far in advance and had enough time to get prepared. As it can be judged from Figure 6, the situation during autumn semester slightly improved. If during Survey 1 81.4% of respondents claimed that they agree or highly agree that they were informed about the requirements and assessment criteria in time and had the chance to get prepared thoroughly, Survey 2 demonstrated a moderate growth of the respondents who answered likewise – 87.6%. Simultaneously, the amount of respondents, who fairly agreed or disagreed that they were informed far in advance declined from 18.6% to 12.4% (Fig. 6). The reason for this improvement was increased awareness of teaching staff on assessment procedures, students’ feedback during Survey 1 and different approach to assessment tasks.

Figure 6.Students were informed about the form of summative assessment and assessment criteria far in advance and had enough time to get prepared. Source: own.

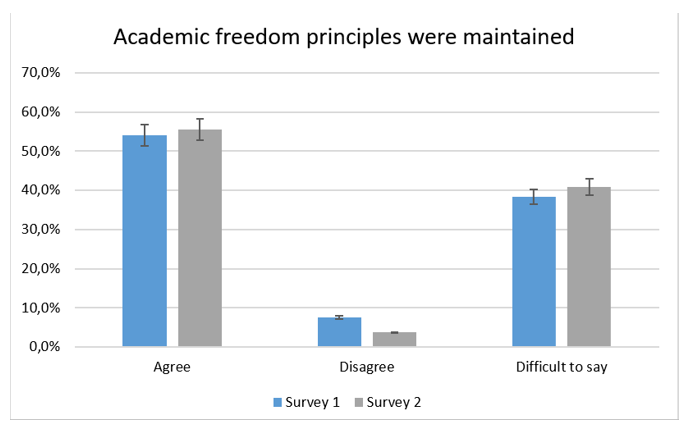

The level of academic freedom has not changed much. If during Survey 1 54% of respondents agreed that methods of teaching and learning are in line with the principles of academic freedom, during Survey 2 this indicator rose only by 1.5% to 55.5% (Fig. 7). The amount of respondents who have opposite opinion almost halved from 7.6% (Survey 1) to 3.7% (Survey 2). The most disturbing indicators here are those connected with students who chose ‘difficult to say’: 38.4 (Survey 1) and 40.8% (Survey 2). The latter two indicators signal about the area for development for the faculty staff, management and student authorities, because more than a third of the students might lack awareness of what academic freedom is.

Figure 7. Methods of teaching and learning were in line with the principles of academic freedom. Source: own.

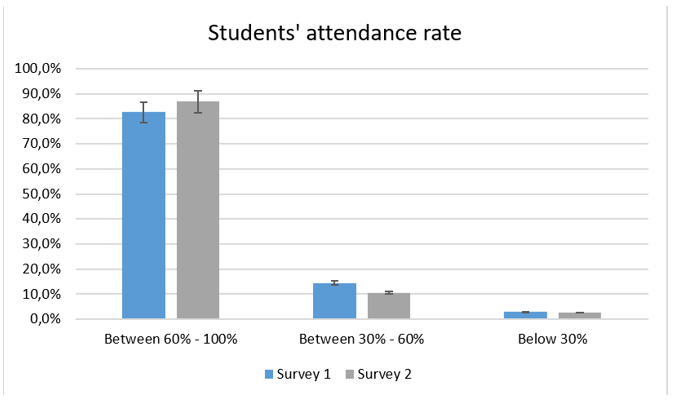

One more indicator of quality assurance is students’ attendance rate. Traditionally it is quite high at the Faculty of Economics and in the framework of two surveys it slightly improved. The percentage of students, who attended between 60%-100% of the classes, improved from 82.6% (Survey 1) to 86.8% (Survey 2), whereas, the percentage of those, who attended between 30% and 60% of the classes, declined slightly from 14.5% (Survey 1) to 10.6% (Survey 2), as well as there was a certain fall among those, who attended less than 30% of the classes, from 2.9% (Survey 1) to 2.6% (Survey 2) (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.The percentage of the classes students joined / attended. Source: own.

In qualitative part of both surveys respondents were asked to outline the problems they faced during remote learning. In Survey 1 the following problems were mentioned:

- No or little feedback from the teachers on the tasks performed

- Too much theoretical material and too many tasks

- Difficulty with acquiring practical knowledge and skills

- Lack of digital literacy among teachers

- Lack of communication with teachers and with peers

However, Survey 2 demonstrated that most of these problems were solved. Students now are getting regular feedback from the teacher on their work, however, they still are lacking the opportunity of individual face-to-face communication with the teacher. Theoretical material and tasks are considered now to be well-balanced, furthermore, with the development of University platform: KNU Education Online students got access to a single platform, where the study programmes are stored, materials, tasks are uploaded. This platform is a one-stop shop, where the real-time classes and webinars can be conducted, materials stored, communication with the teachers occurs, etc. However, the teachers are not limited in using any other platforms and resources they consider to be beneficial for the study process.

Among the current problems students mentioned their need for variety of more sophisticated online tools to be used and so-called ‘Zoom fatigue’. In order to be able to vary the online tools university teachers are attending a number of external and in-house trainings, some of them were specifically oranised for our university teachers: KNU teach week, KNU teach week 2, a course on digital literacy from I-center of our university, etc. In order to tackle ‘Zoom fatigue’ the timetable was adapted: extra 5-minute breaks are now allocated after each 40 minutes of the class. The dean’s office monitors the situation, from time to time it organizes drop-in observations in order to identify if the online classes are conducted, what the rate of attendance is, whether the regulations of breaks are complied, etc.

Conclusions

Regular student surveys appeared to be an effective tool for quality assurance. They not only identify the existent problems, but also help to measure, how successfully these problems are solved and what other areas for development appear. The current research demonstrated how this tool was practically applied during two semesters of remote teaching and learning at the Faculty of Economics in Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. The doubling number of respondents, who participated in Survey 2 compared to Survey 1 proves that the students value the importance of such tool of quality assurance, the see that their voices are heard and their opinion is important for the teachers and the faculty management. Also these two surveys showed that the Faculty is moving the right way under the conditions of pandemic uncertainty and, bearing in mind, that off-line teaching and learning now is ‘a new luxury’, when remote teaching and learning is ‘a new and durable reality’ the experience of the Faculty can be considered as best practice and can be borrowed by other economic faculties or HEIs.