Caught between Two Cultures: Pragmatic Transfer in English-using Pakistanis Apology Responses

Entre dos culturas: transferencia pragmática en inglés con respuestas de disculpa paquistaníes

Abstract

In Pragmatics, scholars have given special attention to study the influence of leaners culture and social rules in understanding and using target language pragmatics. For this purpose, speech acts have been studied quite widely. This study investigates the speech act of responding to apology in Pakistani English, British English and Pakistani Urdu, and tries to highlight whether respondents transfer their cultural and social rules in the target language or not. The present study followed quantitative approach for data collection and analysis. A discourse completion test (DCT), consists of 12 apology response scenarios is used for data collection. The findings illustrate that English-using Pakistanis pragmatic choices are clearly influenced by their perceptions of various sociocultural and contextual variables. The English-using Pakistanis and Pakistani Urdu speakers are found using two main strategies (Acceptance, and Acknowledgment). In contrast, British English speakers tend to use Acceptance and Evasion strategies more often. Further, the findings have indicated that English-using Pakistanis and Pakistani Urdu speakers have used more Rejection strategies than their British English counterparts, though such communicative features are not salient in their ARs, and Pakistanis are surprisingly found quite clear and direct. The findings of the study may be helpful to English teachers who should be made aware that L2 learners’ pragmatic transfer is influenced by learners’ culture and social rules, and, as a result, should not be treated simply as a pragmatic ‘error’ or ‘failure’ to be corrected and criticized.

Keywords

pragmatics, cultural and social rules, apology responses, pragmatic transfer.

Resumen

En Pragmática, los académicos han prestado especial atención al estudio de la influencia de la cultura de los aprendices y las reglas sociales en la comprensión y el uso de la pragmática del idioma de destino. Con este fin, los actos de habla se han estudiado bastante ampliamente. Este estudio investiga el acto de habla de responder a una disculpa en inglés pakistaní, inglés británico y urdu paquistaní, y trata de resaltar si los encuestados transfieren sus reglas culturales y sociales al idioma de destino o no. El presente estudio siguió un enfoque cuantitativo para la recopilación y el análisis de datos. Una prueba de finalización del discurso (DCT), que consta de 12 escenarios de respuesta de disculpas, se utiliza para la recopilación de datos. Los hallazgos ilustran que las opciones pragmáticas de los paquistaníes que usan el inglés están claramente influenciadas por sus percepciones de diversas variables socioculturales y contextuales. Los hablantes de pakistaníes y urdu paquistaníes que usan inglés se encuentran utilizando dos estrategias principales (aceptación y reconocimiento). Por el contrario, los hablantes de inglés británico tienden a utilizar estrategias de aceptación y evasión con más frecuencia. Además, los hallazgos han indicado que los paquistaníes que usan inglés y los hablantes de urdu paquistaní han usado más estrategias de rechazo que sus contrapartes del inglés británico, aunque tales características comunicativas no son sobresalientes en sus AR, y sorprendentemente, los paquistaníes se encuentran bastante claros y directos. Los hallazgos del estudio pueden ser útiles para los maestros de inglés, quienes deben ser conscientes de que la transferencia pragmática de los estudiantes de L2 está influenciada por la cultura y las reglas sociales de los estudiantes y, como resultado, no deben tratarse simplemente como un 'error' pragmático o 'fracaso' para ser corregido y criticado.

Palabras clave

pragmática, reglas culturales y sociales, respuestas de disculpa, transferencia pragmática.

Introduction

Within the framework of interlanguage pragmatics (ILP), Thomas (1983) proposed two kinds of pragmatic failure: sociopragmatic failure, which arises from cross-culturally different perceptions of what constitutes appropriate linguistic behaviour; and pragmalinguistic failure, which is observed when the pragmatic force mapped on to a linguistic token or structure is systematically different from that normally assigned to it by native speakers. One of the major objectives of ILP has been to present evidence for L1 transfer as one of the potential sources for both the sociopragmatic and pragmalinguistic failures (Kasper, 1992).

Pragmatic transfer is described as the way learners’ pragmatic knowledge of their own native language and culture influences their understanding, use, and learning of L2 pragmatic information. Holmes and Brown (1987) opine that through the language acquisition process, apologies have displayed a large amount of pragmatic transfer from first (L1) to second (L2) languages. While Bu (2010), Chen and Yang (2010) and Holmes (1995) illustrate that some transfer is conducive to L2 acquisition, some transfer is not conducive and is instead confusing. The latter form of pragmatic transfer results in what would be termed pragmatic failure and is described by Thomas (1983), one of the foremost researchers of pragmatics, as an area of cross-cultural communication breakdown which has received very little attention from language teachers.

A number of studies have been conducted, in recent years, to investigate pragmatic transfer that is described as the use of one's own cultural norms of speech into the learned L2 language (Haider, 2019; Takimoto, 2020; Chang & Ren, 2020; Al Masaeed et all, 2020; Kádár & House, 2020; Cohen, 2020; Zaferanieh et al., 2020; Malmir & Derakhshan, 2020; Sperlich, et al., 2020). As Pakistani English learners master writing, reading, speaking and listening, many still struggle with communicative competence because of pragmatic failure (Shamim, 2008; Jabeen and Akhtar 2013). An area of specific interest in pragmatic transfer research is responding to apology or apology responses (ARs). The apology speech acts in recent years have been mostly studied from sociopragmatic perspective owing to its relation particularly with pragmatics and generally with sociolinguistics issues (Al-Sobh, 2013). Although, it has been acknowledged by the scholars in the field of pragmatics and sociolinguistics that ARs phenomenon is universally applicable in human cultures and languages, yet it has been recognized as a cultural-specific phenomenon as it is based upon a number of social aspects which differ between languages and cultures (Olshtain & Cohen, 1983).

Several researches on the apology act have been performed (Majeed & Janjua, 2013; Sultana & Khan, 2014; Saleem, Azam & Saleem, 2014) in Pakistan without investigating the potential response of the offended. This study focuses on the pragmatic transfer of English-using Pakistanis apology responses. As discussed above, there is scarcity of research being conducted on the pragmatic transfer in English-using Pakistanis apology responses. It is pertinent to mention that the current study is the first in its nature being conducted with the professional users of English language in Pakistan. Though, there has not been conducted any study on ARs in Pakistan, yet a few studies were conducted on apology strategies (not apology responses) and the researchers had their participants from university students without giving special attention to pragmatic transfer. The current study examines ARs because they are found to be of linguistic and cultural significance.

Literature Review

The apology speech act is defined by the scholars in several ways. Apology is defined as behabitive speech acts by Leech (2007). Keeping in mind the social potential of apology speech act, Olshtain and Cohen (1983) views it quite important speech act for the smooth functioning of different social roles in a society. Meanwhile, Leonard et al. (2011) regarded apology as a convivial conversation act.

According to Agyekum (2006), apology is a speech act that shuns the insecurity between the speakers. It is also stated that apology is a speech act that restores interpersonal relationships and eschews ill-thoughts between speakers after the occurrence of an offense. In addition, apology is also regarded as an appearance of regret, shown by the speaker (offender) to the interlocutor as one makes an offense (Holmes, 1995).

Majeed and Janjua (2013) regard apology as a supportive act that structures to recover the public balance and stability among the speakers. The apology speech act occurs when any expression is used to restore relation between speakers as a consequence of an offense (Saleem, Azam & Saleem, 2014). It can be expressed at the occurrence of the breech of certain cultural-specific customs (Sultana & Khan, 2014). Nevertheless, as experts have mentioned, the speech act of apology is not restricted to the spoken expressions, but relates any event that supports in reinstating the interlocutors understanding. The expressions like ‘I’m sorry’; ‘I beg pardon’ might be included in the face-saving acts including other verbal or non-verbal expressions (Majeed & Janjua, 2013).

Having said this, apology plays quite a significant role in everyday conversations. It is the mostly used speech act in natural ‘languages’. In recent decades, there has been conducted a number of studies keeping in mind its relations with intercultural, cross-cultural and inter-language perspectives.

Apology Responses (ARs)

Bachman and Guerrero (2006) argue that responding to apology is a culture-specific trend; it is of importance for speakers of another language to be acquainted with cultural aspects of target language. Having gained competency in syntax, phonology, morphology and lexicology does not guarantee you of interacting efficiently in the target language (Leech, 2007). This aim can be achieved by giving special attention to pragmatic competence (Kasper, 1992). There have been many studies carried out on the speech act of apologies in East and West, however, no study on apology responses (ARs) is undertaken. Therefore, it is pertinent to investigate the potential responses of the offended person in order to keep strong interpersonal relations (Adrefiza & Jones, 2013).

Nevertheless, a number of studies have been conducted on the speech act of apology, but special attention has not been given to Apology Responses (ARs). Experts in the field have highlighted that responding to apology plays a significant role in order to keep healthy exchanges (Auer, 2020; Bachman & Guerrero, 2006). They believe that ARs can offer the circumstances which are quite substantial for restoring interpersonal relationships and in keeping a balance in the society. In other words, the execution of such events is mostly determined by the natures of responses from the interlocutor or the affronted individual. As mentioned by McCullough, Pargament et al. (2000) ARs apart from language, sociolinguistics and pragmatic competence have been studied from psychological and religious perspectives as well.

Apology Acceptance Strategies

It has been acknowledged that responses to apology are being expressed in different ways, from silence to many kinds of language expressions, and apology response strategies are (Bachman & Guerrero, 2006) divided into several broad categories. These are: accept (AC), acknowledge (AK), evade (EV) and reject (RJ) (Bachman & Guerrero, 2006). Experts in the field have mentioned that ARs have been demonstrated in a number of ways based on different main and extended strategies, among them mostly used strategy is absolution “That’s alright” or “That’s okay” was recommended reaction to regret, especially in United States and British exchanges Witvliet et al., 2020; Robinson, 2004).

The use of absolution “That’s alright” consists of an “indexical phrase” such as “That’s” and an assessment such as “OK” or “alright” (Bachman & Guerrero, 2006). Here the expression that includes the “indexical phrase” may not make reference to the expressions and feelings of regret, but to the offense being happened. The expressions based on the terms “That’s alright”, “That’s OK” mainly highlights interlocutors’ understanding of the offense, illustrating that the interlocutor does not believe that the transgression is quite severe and consequently disregards the offense and mitigates the situation by using such expressions (Witvliet et al., 2020).

Apology responses have been occurring in our daily conversations, it is pertinent to have proper knowledge of responding to apology keeping in mind different social factors that determine our use of apology responses. It must be acknowledged that non-native speakers often fall victim of interpreting the situations of ARs according to their own culture and use inappropriate expressions to mitigate the face-threatening act which in consequence ends with pragmatic failure (Kasper, 1992). The knowledge and pragmatic awareness is essential for smooth social interaction in the target language. Many a studies have mentioned that non-native speakers (NNS) often embarrass themselves by their miscommunication and fail to restore interpersonal relations owing to lack of appropriate pragmatic knowledge (Khorshidi Mobini & Nasiri, 2016). In this regard, the present research focuses on the investigation of pragmatic transfer in English-using Pakistanis apology responses (ARs) to highlight any difference if exist among Pakistani English users, British English speakers and Pakistani Urdu speakers.

Methodology

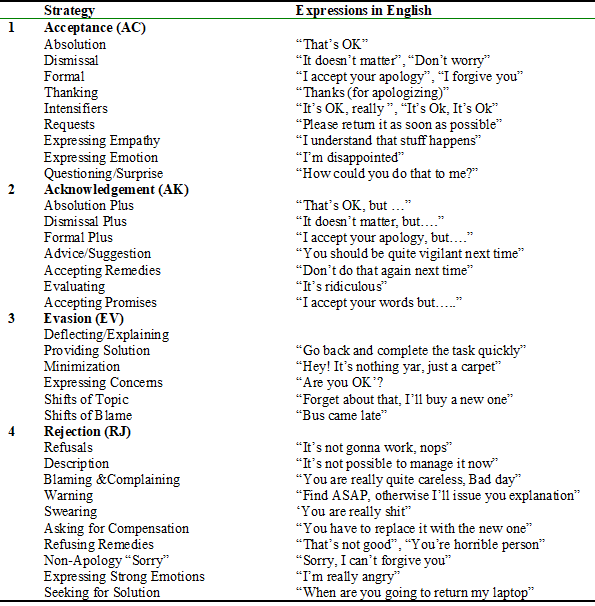

Quantitative approach has been adopted in this study to investigate pragmatic transfer in English-using Pakistanis apology responses in order to highlight cultural impact on participants’ possible realization of semantic formulaic. The study involved 50 (25 male & 25 female) English-using Pakistanis as target language group (EuP), 50 (25 male & 25 female) British English Speakers (BritE) from Coventry University, UK, University of Leeds, UK, and British Association of Applied Linguistics (BAAL) members, and 50 (25 male & 25 female) Pakistani Urdu speaker (PakU), both EuP and PakU groups consist of (teachers, academicians, lawyers, journalists, doctors, engineers, and army personals) whose age ranged from 25-55 years, English native speakers age ranged from 25-65 years . EuP and PakU respondents were selected using non-random, purposive, and convenience sampling procedures from Lahore and Islamabad. Keeping in mind the nature and aims of the study, a Discourse Completion Test (DCT) including (translated in Urdu versions for Pakistani Urdu speakers), was developed by modifying those situations used in the previous studies containing 12 items (Thijittang, 2010). We discussed and supervised the DCTs personally. After the data were processed through coding, and were run through the statistical software for the social sciences (SPSS-21). The results were reported through summary narrative approach to present a realistic description of linguistics and pragmatic features realized by respondents in PakE, BritE and PakU. All participant responses were categorized into main and extended classifications categorized by Adrefiza and Jones (2013). AR strategies and sub-strategies are classified in the following table.

Table 1.

Apology Response Framework.

Results

The results of the main categories of apology responses are reported in the following section.

Acceptance

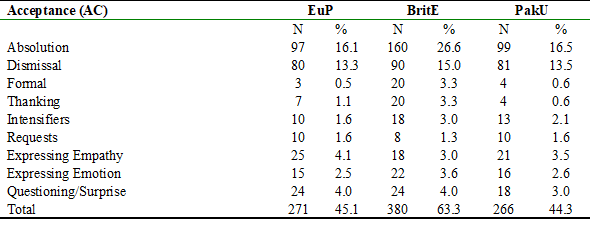

A number of extended AR expressions have been included in the AC category of ARs. Overall, absolution, dismissal and formal approval is the style in which "acceptation" is expressed. It also incorporates other expressions of subsidiary terms such as gratitude, intensifiers, demands, empathy, emotional expressions and questions/surprises. Cumulatively, a reasonable proportion of acceptance techniques have been performed by the three groups.

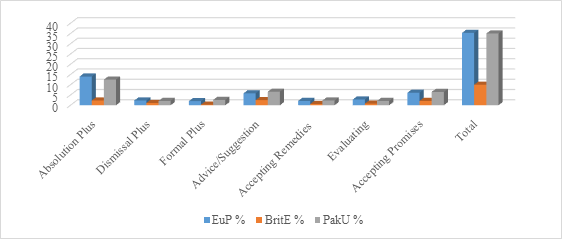

However, BritE interlocutors prefer, (63.3%) to use more techniques of AC than EuP (45.1%) and PakU (44.3%) interlocutors. A rigorous analysis on the application of prolonged expressions and tactics of the three groups presented in the table 2 and figure 1. It is evident that the usage of AC techniques differs with respect to the sociocultural transfer of EuPs. It is clear that EuPs and PakUs differ from BritE in expressing certain subsidiary AR acts and terms.

Absolution, formal, gratitude and questioning AC techniques demonstrate the apparent differences among the three groups. In BritEs ARs, Absolution ARs (26.6.5%) are far more frequent than in EuPs (16.1%) and PakUs (16.5%). Three groups, in addition, prefer to use Dismissal ARs as much as possible. There is no difference in Dismissal ARs of three groups (EuP, BritE and PakU) with a proportion of (13.3:15.0:13.5). Although the AC rate is very high in BritEs ARs, even so AC is not very low in EuPs and PakUs ARs. Table 2 and figure 1 present the detail.

Table 2.

Extended ARs in Acceptance Classification.

Figure 1. Extended ARs in Acceptance Classification

In BritEs' responses (3.3%), the use of formal approval is alsovery strong. On the other hand, both EuPs (0.5%) and PakUs (0.6%) appear to realize less formal AC technique. BritEs also demonstrate more Thanks and Intensifiers Acceptance (3.3% and 3.0%) than the other two groups. The three groups most commonly expressed ARs for communicating empathy, communicating emotion and interrogation/surprise AC techniques without any tangible distinction.

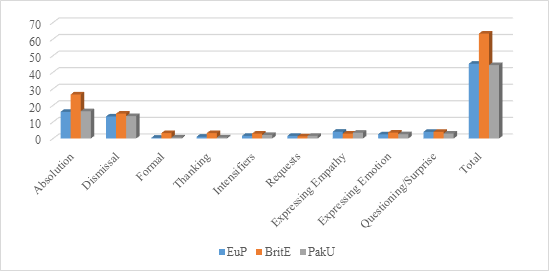

Acknowledgement

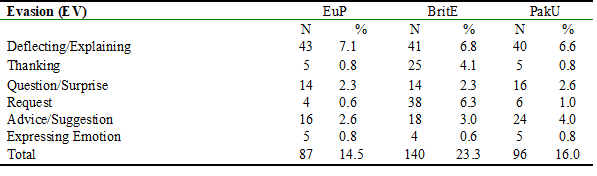

The difference in the realization of elaborated ARs and terms in AK category is quite observable among the three groups. Primarily, the AK classification comprises a range of subsidiary ARs and a variety of terms such as Advice/Suggestion, Accepting Remedies, Evaluating, and Accepting Promises. EuPs and PakUs in general prefer to express more subsidiary AK ARs than the BritEs with a proportion of 35.3:35.0:10.0 each. It can be seen in table 3 and figure 2, EuPs and PakUs prefer to perform more subsidiary terms of AK than BritEs. Further, EuPs and PakUs outmanned in performing Absolution plus category with (14.0% and 12.5%), on the contrary, BritEs (2.3%) prefer to perform less Absolution plus technique. Besides, BritEs (1.1%) prefer to perform less Dismissal plus technique, in contrast, both EuPs (2.3%) and PakUs (2.1%) ARs are based on Dismissal plus technique.

Table 3.

Extended ARs in Acknowledgement Classification.

Figure 2.Extended ARs in Acknowledgment Classification.

Moreover, in EuPs (2.0%) and PakUs’ (2.6%) responses, Formal Acceptance AR technique happens more frequently than BritEs (0.3%). There is another technique Advice/Suggestion that is more frequently performed by EuPs (5.8%) and PakUs (6.6%) than BritEs (2.5 %). Moreover, EuPs (2.1%) and PakUs (2.3%) prefer to perform more Accepting Remedies technique than BritEs (0.6%). Nevertheless, Evaluating is another AR technique less frequently performed by BritE (0.8%) speakers than EuP (2.8%) and PakU (2.1%) speakers. Similarly, realizing Accepting Promises AR technique indicates that both EuPs (6.1%) and PakUs (6.5%) prefer to perform this technique more often than BritE speakers (2.1%).

Evasion

Acute discrepancies are found in the usage of prolonged expressions of evasion in the three groups ARs. Mostly, EV includes deflecting, and other subsidiary ARs, including questions/surprises, demands, advice/suggestions and emotions of speech. Surprisingly, BritEs appear to use more EV techniques, while their use of such language actions is thought to be straightforward and explicit. In contrast to Acknowledge and Reject techniques, BritE interlocutors seem to perform EV technique more frequently than the EuP and PakU speakers. Unexpectedly, as can be noticed that both PakU and EuP speakers appear to express less EV subsidiary terms, while as stated previously, their speaking behaviour is mostly comprised of ambiguous and implicit traits specifically in AR acts that require speedy response.

Table 4.

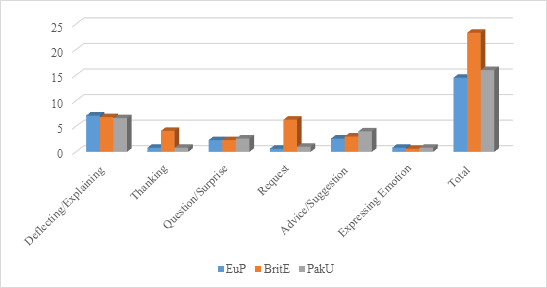

Extended ARs in Evasion Classification.

Figure 3. Extended ARs in Evasion Classification.

Table 4 and figure 3 indicate that BritE interlocutors appear to realize EV technique more regularly that PakU and EuP speakers with a proportion of 23.3:14.5:16.0 respectively. In addition, BritE interlocutors seem to express Thanking (4.1%) apology responses more frequently than EuP (0.8%) and PakU (0.8%) interlocutors. Another technique more often expressed by BritE (6.3%) than EuP (0.6%) and PakU (1.0%) is Request ARs. Therefore, Deflecting/Explaining, Advice/Suggestion, Question/Surprise, and Expressing Emotion techniques are nearly evenly realized by the three groups.

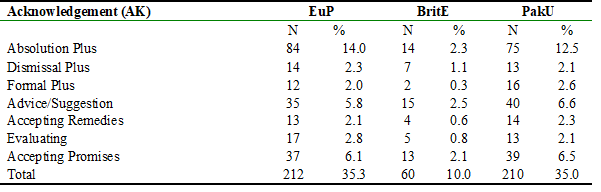

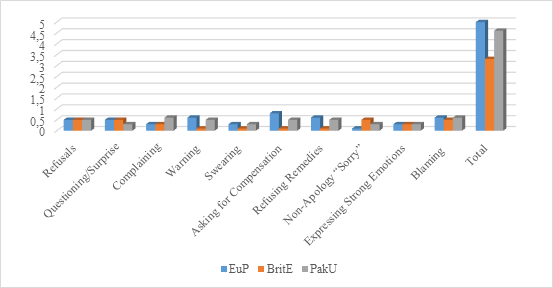

Rejection

The speakers acknowledge that the RJ conversation act is very complex in nature, in contrast to other types of the apology responses by means of a variety of elaborate actions. The results of the RJ strategy suggest that this act of speech is more face-threatening and destructive than it is subtle and complicated. Although it does not occur as often as the other speech acts, it has a substantial impact on speech bahaviour, including cultural limitations. Nevertheless, it characterizes a variety of widespread expressions and speech acts, for example “Refusal”, “Rejection with Questioning/Surprise”, “Rejection with Complaining”, “Rejection with Warning”, “Rejection with Swearing”, “Asking for Compensation”, “Rejection with Refusing Remedies”, “Rejection with Non-Apology, Sorry”, and “Expressing Strong Emotions”.

Table 5.

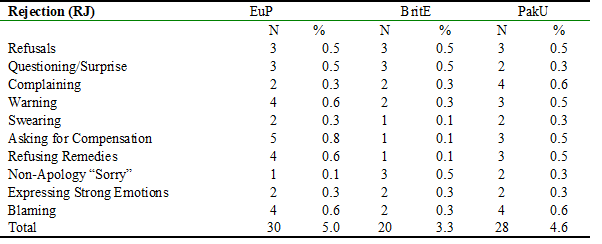

Extended ARs in Rejection Classification.

Figure 4. Extended ARs in Rejection Classification

In addition, the variations among the three groups realization of subsidiary RJ ARs are shown in Table 5 and Figure 4. Findings demonstrate that the RJ techniques of both EuP and PakU groups are significantly higher than those of BritE with a proportion of 5.0:4.6:3.3 each. Nevertheless, Refusals (0.5%, 0.5% and 0.5%), Questioning/Surprise (0.5%, 0.5% and 0.3%), Complaining (0.3%, 0.3% and 0.6%), Warning (0.6%, 0.3% and 0.5%), Swearing (0.3%, 0.1% and 0.3%), Asking for Compensation (0.8%, 0.1% and 0.5%), Refusing Remedies (0.6%, 0.1% and 0.5%), Non-Apology “Sorry” (0.1%, 0.5%, and 0.3%), Expressing Strong Emotions (0.3%,0.3%, and0.3%), and Blaming (0.6%, 0.3%, and 0.6%) categories are found quite often in English-using Pakistanis, British English speakers and Pakistani Urdu speakers’ responses.

In addition, EuP and PakU data shows high rate of incidences of these strategies with a proportion of Warning (0.6% and 0.5%), Asking for Compensation (0.8% and 0.5%), and Refusing Remedies (0.6% and 0.5%) than BritEs Warning (0.1%), Asking for Compensation (0.1%), and Refusing Remedies (0.1%).

Discussion and Conclusion

The findings of AR strategies employed in PakE, BritE, and PakU speakers reflect how the three groups respond to the interlocutors’ regret in their efforts to recover individual connections and balance. Aside from individual and communal factors, the use of AR techniques may signify the interlocutors’ efforts to maintain individual relations and balance in the community. The results demonstrate both individual and public tokens of respect and camaraderie; both these aspects are surprisingly involved in the choice of the techniques in responding to apology. The findings of the current study acknowledge the recommendations of Paltridge (2004), who considers that these aspects along with other reasons, such as level of social power and social distance between interlocutors, level of imposition, age of members, and the gender of the interlocutor, play a vital part in the speech act of ARs. Some aspects of these factors also seem to connect with the understanding of ARs.

Though, the speakers are different in regards to social power and social distance, the AR technique choice is different from participant to participant. Still, it must be recognized that the information signifies only a part of Pakistani and English cultures; so a little difference of AR techniques in the three groups that are obvious here may be observed as a sign of the type of conversation act behavior trend that may be thought from three groups, especially in using ARs.

The results also display that there is variation in the use of ARs, BritE interlocutors prefer to perform more AC techniques than EuP and PakU speakers. As table 2 illustrate, both EuP and PakU speakers have realized almost same proportion of AC strategies, indicating the transfer of cultural norms from L1 to target language. The other reason of similar type of responses in both EuP and PakU can be attributed to the fact that Pakistanis both in English and Urdu over-use the words like “It’s Ok” (Khair he), “It’s alright” (theek he) etc. Moreover, EuP and PakU interlocutors seem to realize more Acceptance tactics, providing evidence that Urdu language obstacle English-using Pakistani in producing and perceiving ARs inappropriately while keeping in mind pragmatic competence. As the data from BritE speakers demonstrate that they prefer to use the expressions “That’s OK”, in this expression “That” is used as an indexical term that refers back to that offense. In contrast, EuPs tend to use AR expression like “It’s OK”, “It’s alright” etc. It happens because of the translation from Urdu language (Theek he, khair he), the word “he” motivates the EuPs to translate it into English because ‘he’ works as copula verb “be” in Urdu language. This inappropriate use of ‘he’ being translated into ‘it’ illustrates the negative pragmatic transfer of the EuPs indicating lack of knowledge and inadequate understanding of target language culture. A few examples from the data have been presented as an evidence to observe how apologies are accepted in EuP, BritE, and PakU:

Employee forgot to pass on an urgent letter to boss. (Situation1)

Employee: Sorry Sir, I forgot to pass it to you. It won’t happen again.

EuP: It’s OK. Be careful next time.

BritE: That’s fine. No problem.

PakU: theek he. Koi masla nai. lao ab muje de do.

(Translation: That’s OK. No problem. Now you can give me)

So, this wrong perception of exact translation of expression in target language strengthens the concept of negative transfer of sociocultural norms to the target language. Apart from negative transfer, Urdu language, to a great extent provides its users the equivalent expressions in English. As far as the politeness patterns of EuP and PakU are concerned, the findings of the present study acknowledge Rahman’s (1998) argument that EuP and PakU speakers do not follow Brown and Levinson’s (1987) hypothesis of politeness, rather they use politeness strategies for the utilitarian purpose of gratification. The data of present study indicates that British English speakers do not use the honorific “Sir/Ma’am” for higher social status interlocutors, and at the same time, they are not found using honorific like “dear” for interlocutors of lower/equal social status interlocutors but u and PakU tend to use honorifics like “Sir/Ma’am” for higher social status participants and ‘dear’ for lower/equal social status interlocutors as many as they could, this phenomenon illustrates the use of cultural-specific ARs and indicating negative pragmatic transfer in target language which may cause miscommunication because the use of such expressions are supposed ominous in the target language culture (Rahman, 1998).

The results, however, display a few extra phenomena appealing to the current study. First, three groups are generally rather self-denying and other-oriented in their AR behaviors. This is shown by the proportion of AC strategies are used by the participants in each of the three groups. Same idea has been advocated by the previous research findings as well. The most relevant studies are of Owen (1983), Holmes (1995), and Robinson (2004), who all report that AC of an apology is the most recommended AR. Simultaneously, the regularity of Recommendation is clearly rich in PakE and PakU data exposing that in Pakistani lifestyle, beneficial respect have frustrating control in ARs. It seems that the participants absolutely limit their self-oriented behaviors. The presence of AC strategy in the current study seems to acknowledge the findings of Chang and Ren (2020), who recommended that apology is hardly ever refused indicating that Pakistan is though a non-egalitarian society as mentioned by (Kousar, 2015) but still social and religious factors play quite a vital role in responding to apologies. The data in PakE and PakU exhibit that both groups’ respondents tend to use less EV and RJ strategies, and preferring the use of more AC and AK strategies also indicating that EuPs incline to use ARs having kept in mind social and religious norms and values, as Islam teaches and believes in forgiving and restoring relationships.

It is worth noting that the respondents of three groups tend to favor the use of AC strategy more often than the other three categories. This seems to remain true with the social features of the Pakistani community, who are said to be a part of two basically different kinds of lifestyle. As Hofstede (2011), Sawir (2014), Darine and Hall (1998) and Klopf and McCroskey (2006) argue that Pakistan is usually associated with Asia and collectivist lifestyles, while UK is usually believed to be European and individualist. The two are considered to stand out from one another in many aspects, such as how public relations are strengthened and maintained in a society. In a collectivistic community, such as Pakistan, individual and public connections are usually more powerful than those in individualist nations such as UK because public interaction activities are distributed in groups much more intensively than in an individualist community. Collectivist lifestyle is also said to be more resistant than individualist lifestyle. Obviously, as one would anticipate AC to happen more often in PakE (45.5%) and PakU (44.4%) than in BritE (60.7%). However, such a difference is not obvious here. Instead, both cultures usually are similarly “polite” in their AR behaviors as indicated by their use of ‘Acceptance’ strategies.

Another exciting trend that can be observed in the outcomes is the proportion of EV techniques in use. The reason that EuPs and PakUs display a least occurrence in EV than the BritEs seem to encounter one of the typical generalizations about the conversation designs of the three groups. These generalizations develop in a typical difference made about interaction behaviors between High Perspective and Low Perspective societies. Basically, suggested by Wouk (2006) and Hofstede (2011), Eastern countries such as Pakistan is believed to be HC, so their conversation behaviors seem to be regarded uncertain, implied, and indecisive, Westerns, instead, are usually considered LC and precise, specific, and candid. Evasion actually is an HC attribute as it reveals a large degree of indirectness and deflective actions on the part of the interlocutor. Therefore, Rahman (1998) further discusses that individuals from an LC lifestyle sometimes find it tough to understand persons from HC as their conversation purpose may be uncertain. Such conversation functions are popular in Pakistani community. In the existing research, however, such functions do not appear noticeably. Amazingly, English-using Pakistanis seem to go to express themselves less evasively than regular. In contrast, British English speakers tend to express their ARs evasively (26.5%) much frequently than usual. The findings are in line with Australian English speakers’ responses who also favor the use of more evasive ARs, exhibiting the traits of being more implicit, indirect, and unforeseen than usual (Adrefiza & Jones, 2013).

The relatively significant number of EV technique in British English may associate to the understanding of public image and respect concepts. It might be the case that, for most British participants, the use of an EV strategy is an approach designed to display solidarity and pay regard in order to decrease the face-threat or face-loss towards the interlocutors following a painful occasion. The participants may reflect precise reactions as face-threatening and too immediate in the given conditions. Hence, EV AR strategy is believed to be the most appropriate technique in certain situations. In Pakistani community, in comparison, such conceptions are probable to be recognized rather in a different way. The participants do not look to understand EV as an approach to display solidarity or regard which has possibility to decrease face-threat, but rather as something which specifies vagueness. In addition, EuP and PakU interlocutors favoring to express their apology responses more explicitly and more directly than BritE interlocutors encounters the HC stereotype of Pakistani society. Nevertheless, look at the following responses of ‘Evasion’ in PakE, BritE and PakU:

The presentation was not smooth because colleague did not prepare well. (Situation 12)

Colleague: Sorry dear we couldn’t do well. Anyhow, don’t worry dude, why are you upset. It’s just a presentation. We’ll do it again. Come on buddy, I’ll not let you down.

EuP: Oh God! It was not just a presentation. It was our only hope to win the trust and annual appraisal from the cabinet members. Anyways let’s see what we are gonna to do now. Honestly speaking, I have very little hope upon you.

BritE: We have already wasted a lot of time. Shall we have a look at the report?

PakU: Yar Allah Allah kar ke mene report tayar ki thi. Laikan tumhari kamzoor tyari ki waja se hum acha na kar sake. Chalo dobara loshish karte hen.

(Translation: Dear! I had completed report after having a lot of trouble but your weak preparation didn’t allow us to do well. Let’s try again)

Another exciting trend is the fact that three groups do not place their AR techniques between the negative and positive continuums. Basically, AR categories, AK and AC signify a beneficial mind-set, while RJ and EV display the reverse that is a damaging action of the participants. It is recognizable that the ARs of British English speakers fall more into AC and EV continuum (positive and negative), in contrast, EuPs and PakU interlocutors prefer to express equal proportion of AC and AK (only positive), showing a discrepancy in this continuum. This result may suggest that BritEs have shown a mixture of positive and negative behaviors in demonstrating their ARs while EuPs and PakUs have revealed only positive behavior. Anyhow, the data of BritE is in line with the findings of (Adrefiza & Jones, 2013; Allami & Naeimi, 2011), who suggested that English as a second language/foreign language learners tend to be less positive and more negative.

As mentioned previously, the both EuPs and PakU interlocutors prefer to realize more frequently AK strategy than the BritE interlocutors with a proportion of (35.2:35.7:9.5). The incidence of this technique reveals individual or social power aspects exist in the Pakistani lifestyle. For many Pakistanis, acknowledging an apology can be observed as individual pride, signaling a feeling of unwillingness not to let the perpetrator entirely out of trouble. For them, permitting the culprit completely get free after an unpleasant occasion may be identified as challenging, and cause harm to their self-dignity, arrogance, firmness, or stability. The illustrations below show proof how acknowledgement is indicated in PakE, BritE and PakU:

A colleague stepped foot on you in a crowded elevator. (Situation 8)

Colleague: Excuse me buddy, I was in hurry. You fine?

EP: Yeah! That’s cool. But buddy try to lose your weight please don’t mind my words. It’s just a suggestion if you accept it.

BE: Yes, I’m OK. But don’t call me ‘buddy’ though. And please walk carefully!

PU: ‘O’! Khair he bus zara aap ikhtiat se chalain

(Translation: Oh! That’s fine. But you walk carefully)

Therefore, they quite often identify their ARs with a certain face-threatening expressions such as guidance, suggestions, or caution, which designates a meager approach to the acceptance of the apology. Such expressions, however, are not well-known or suggested in Western societies, as may be considered by the low frequency of Acknowledgment in British English speakers ARs.

Lastly, the incidence of a least proportion of RJ in PakE, PakU, and BritE reveals another exciting trend. As AC symbolizes the speaker’s other-oriented and self-denying actions (Hofstede, 2011), RJ can be considered as the other (self-oriented and other-denying). These unexceptional occurrences of RJ in the findings of the current study indicate that EuPs and PakUs are self-denying and other-oriented; they are able to cover up their harm emotions following an offence or wrongdoing dedicated by their interlocutors. They prefer to show their positive bahaviour while using the face saving expressions and have a tendency to have patience of an interlocutor’s wrongdoing.

Junior copied an article from a website for his/her presentation. (Situation 4)

EuP: Bhai sab! Always keep your mind and eyes open, and always try to write and produce your own work, avoid copying, and note down, if you ever do again, I will not spare you. Mind it, you will be gone.

BritE: Ok, but it’s pretty serious. Let me think about what we need to do here and I’ll get back to you.

PakU: Dekho larke har cheez ki ek had hoti he. Tume men copy karne ki bilkul ijazat nehi doon ga. Abhi men maaf karta hoon or ainda esa nai hona chahye.

(Translation: Look boy, everything has its limits. I‘ll not allow you copying. I’m sparing you this time and don’t do it in future)

The responses of EuP and PakU seem to be face-threatening but it might be owing to the severity of the situation that demands to be strict in their ARs. Further, another exciting phenomenon is the use of socio-cultural specific expression of politeness is ‘Bhai sab’ (dear brother’, helps the speaker to mitigate the situation and makes ARs less face-threatening. The use of such expression indicates the influence of culture-specific behavior in the target language. Nevertheless, the use of ‘always keep your eyes and mind open’ is a face-threatening act. At the same time, BritE response also shares face-threatening expressions (OK, but it’s pretty serious). The realization of intensifier ‘pretty’ indicates the severity of the offense. Anyhow, it is significant to note that the frequency at which RJ occurs in PakE and PakU is slightly higher than in BritE with a ratio of (4.9:4.3:3.2). While the information is inadequate to attract a generalization, the outcomes could signal that EuPs and PakUs tend to be more rejecting. As discussed by Gorsuch and Hao, (1993), and Poloma and Gallup (1991), the findings may then defy the supposition that, in Pakistani community, an absolutely religious community, the percentage of being rejected should not be higher than English BritE speakers, given that being rejected is a serious affront. Previous researches have shown that denials of an apology are less regular in religious countries as RJs are against religious teachings. It is pertinent to mention that it is a directing concept in Islam and in Christianity to use absolution, which is the complete reverse of being rejected. However, it is possible that the amount of severity of the offence, the connection between the culprit and the upset personal, and the scenario in which the apology happened may have impacted the characteristics of the reactions here.

Conclusion

The study concludes that the participants of PakE and PakU tend to use only two main categories of ARs (AC and AK). In contrast, British English speakers prefer the use of AC and EV strategies. British English speakers ARs fall in both positive and negative continuum, on the other hand, English-using Pakistani and Pakistani Urdu speakers ARs only illustrate the positive behavior of politeness patterns. In addition, the current study also shows that both English-using Pakistanis and Pakistani Urdu speakers are found to using RJ strategy more often than the British English speakers. Unsurprisingly, the findings also demonstrate the ample evidence of pragmatic transfer in the AR behavior of English-using Pakistani. They are found exactly translating their ARs from their L1 to L2. The British English speakers’ data illustrate the use of indexical term “That” with “Absolution” strategy but English-using Pakistanis data provide the use of “Absolution” strategy with “It’s” because “It’s” is the literal translation of Urdu word “he”. They have also displayed cultural-specific ARs while responding to different scenarios. The data shows that English-using Pakistani and Pakistani Urdu speakers show quite profound politeness behavior while interacting with the interlocutors of high social status. This phenomenon has been discussed by Rahman (1998) who opines that the over use of honorific “Sir” for higher social status and ‘dear’ for lower/equal social status does not illustrate the politeness of the speakers. In fact, this phenomenon highlights that English-using Pakistanis and Pakistani Urdu speakers tend to use this expression to gratify the interlocutor instead of being polite as mentioned by Brown and Levinson (1987). At length, we, being, the instructors of English language need to teach our students the pragmatics of English language in our classrooms. Unless, we give special attention to teaching and raising awareness of our teachers and students regarding pragmatic competence, we cannot achieve the desired outcomes. We also urgently required revising our curriculum and devising it according to the communicative and pragmatic needs of the ESL learners (Azam & Saleem, 2018a; Azam & Saleem, 2018b; Aziz et al., 2020; Sharqawi & Anthony, 2019). Further, we need to focus on developing our ESL learners’ pragmatic competence including linguistic competence. Because in most of ESL classrooms, special attention is given to linguistic competence and pragmatic competence is rather ignored.