Emblematic Literature as a Form of Biblical Hermeneutics

Емблематична література як форма біблійної герменевтики

Abstract

The article defines the basic principles of the influence of biblical hermeneutics on the poetics of Ukrainian Baroque emblematic literature, which were determined by its general development trends. The four-sense biblical hermeneutics, founded by the Greek and Roman Church Fathers, played an important role in the formation of Ukrainian Baroque literature that mainly developed within the theological framework. The principles of biblical hermeneutics eventually began to go beyond the theological literature. Thus, the medieval interest in symbol and allegory led to the appearance of “empresas” – symbolic drawings that became fashionable at the royal courts of Europe in the 15th century. The Renaissance misunderstanding about the nature of Egyptian hieroglyphs, their perception as ideographic writing through which Egyptian priests expressed their wisdom, led to the appearance of emblems, allegorical prints with long explanatory verses, aimed at giving some moral lessons. It was believed that the emblem could communicate truth to the mind more directly than with the help of words. It was reflected in the mind, while the person’s gaze wandered through the symbolic details of the emblem. The research provides evidence that a large number of literary works of the 17th century showed the influence of the emblem on the formation of symbolic representation, arranged to reveal the truth implicitly or explicitly through the sequential placement of the elements. Many poetic images of the 17th century come from well-known emblems, which were means of perceiving, interpreting, and opening the world of the Bible to the Baroque reader.

Keywords

allegory, Baroque literature, biblical hermeneutics, emblematic literature, emblematic poetry, poetics, symbol.

Анотація

У статті з’ясовано засади впливу біблійної герменевтики на поетику української барокової емблематичної літератури, які були зумовлені загальними тенденціями її розвитку. Чотирисенсова біблійна герменевтика, заснована грецькими та римськими отцями Церкви, відіграла важливу роль у становленні українського барокового письменства, яке розвивалося переважно в теологічному річищі. Принципи біблійної герменевтики з часом стали виходити за межі власне богословської літератури. Так, середньовічна зацікавленість символом й алегорією спонукала появу “empresas” – символічних малюнків, які стали модними в європейському придворному світі ХV ст. Нерозуміння епохою Відродження природи єгипетських ієрогліфів, сприймання їх за ідеографічне письмо, за допомогою якого єгипетські жерці виражали свою мудрість, стало причиною появи емблем, алегоричних естампів з довгими пояснювальними віршами, задуманими з метою викладу моральної науки. Вважалося, що емблема має здатність сповіщати істину розумові більш безпосередньо, ніж за допомогою слів, відображаючись у ньому, доки погляд блукає символічними деталями емблеми. Дослідження засвідчує, що велика кількість літературних творів XVII ст. демонструють вплив емблеми на формування символічного уявлення, влаштованого таким способом, щоб відкривати істину імпліцитно або експліцитно в послідовному розміщенні елементів. Чимало поетичних образів XVII століття походять від знаних емблем, які були засобами сприйняття, тлумачення та відкриття світу Біблії для барокового читача.

Ключові слова

алегорія, барокова література, біблійна герменевтика, емблематична література, емблематична поезія, поетика, символ.

Introduction

The method of interpreting the Old and New Testaments, which considered the spiritual sense of the Bible, hidden behind the verbal signs, to be closer to the absolute truth, played an important role in the formation of Ukrainian Baroque literature.

This issue was partly studied from various methodological and ideological perspectives by many Ukrainian and foreign literary scholars, including D. Chyzhevskyi (1934; 1991; 2003), B. Krysa (1997), L. Ushkalov (1994; 1997; 1998; 1999a; 1999b; 2011; 2014; 2016), as well as Z. Lanovyk (2006), N. Levchenko (2018a; 2018b; 2019a; 2019b), P. Lewin (1984), O. Liamprekht (2006; 2007; 2016), O. Matushek (2000; 2013), O. Zosimova (2003; 2007; 2008) and others.

Hermeneutics as a theory of interpretation of sacred texts was formed and developed during a long period of time – from the ancient Jewish tradition, works by Augustine (1835) and Origen (1993) to the modern theories of H.-G. Gadamer (2001), F. Kermode (1979), W. Iser (1996) and others. Having its origins in the Old Testament Book of Genesis (1445 BC), biblical hermeneutics started more than three thousand years ago and continued to evolve and improve over time. It underwent profound transformations in the Middle Ages, during the Reformation and Modernism, but remained at the heart of not only literary studies, but also cultural and philosophical research because of the special nature of its only object of study, namely the Holy Scriptures.

The authors of this article aim to outline the general principles of the influence of biblical hermeneutics on the poetics of Ukrainian Baroque emblematic literature.

The lack of scholarly research on emblematic texts as a form of interpretation of the Bible, as well as the importance of this type of texts for the Baroque literature and way of thinking as a whole, determine the topicality of our study.

Methods

To accomplish the research goals within the framework of the hermeneutic method we followed the principles of polysemy, parallelism, paraphrase, two-tier completeness of meanings within the spiritual and corporeal parabola, four-sense (literal, allegorical, moral and anagogical) interpretation of the Scriptures and extrapolation of the New Testament from the Old Testament; contextual, symbolic, Christological, typological, metatextual and intertextual principles of biblical interpretation.

Results and discussion

In order to achieve greater persuasiveness in depicting life (both in the form and content of these descriptions), Baroque writers referred to and relied on the supreme and unshakable authority of the Bible. It influenced the formation of the genre system, ideas and themes, artistic categories, and imagery as well as moral and philosophical orientation of literary works.

The Christian writers of the past, who were chiefly monks and clergymen, saw the Bible as a collection of books written by the Holy Spirit through hagiographers. The mysteries of existence and non-existence, which had been explained by Hermes in Greek mythology, were to be clarified by the Bible with the advent of Christianity. It was considered the Word of God, subtle and incomprehensible to ordinary people, and therefore it could not be perceived as a text that was easy to understand. Besides, the Bible is full of metaphors, similes, allegories, and parables, which also made it difficult to perceive Scripture. Among the serious obstacles to mastering the techniques for understanding the Bible there is a time gap of more than 1,600 years from the time, when the Holy Scriptures were created, to the Baroque epoch in Ukraine, differences in the culture and worldview of ancient Jews and Ukrainians as well as the linguistic imperfection of the Bible due to its translation (it is well-known that even the best translation cannot fully convey the meaning of the original). Therefore, in order to avoid spontaneous perception of the Scriptures, methods of interpreting and explaining the Bible were to be developed. Biblical hermeneutics became the science that set out the rules of interpretation of the Holy Scriptures. The spread of Christianity encouraged the theoretical development of this science.

Being based on the method of philological hermeneutics, biblical hermeneutics made some adjustments to its structure by changing the subject of interpretation. The interpretation of fiction texts was free, while the interpretation of the texts of the Holy Scriptures required a comparison of the consequences of interpretation, which theoretically had to satisfy the needs of religious cults, though in practice it was not always possible.

L. Ushkalov (1998b) emphasizes the considerable influence of the views of the Western and Eastern Church Fathers on the reflections of the Ukrainian Baroque writers. For instance, speaking about the work of Meletii Smotrytskyi, the researcher notes:

The list of theologians whose arguments served as the “matter” for thought plots, which Meletii Smotrytskyi provides in his “Trenos”, is as follows: Albert the Great, Ambrose Aurelian, Anselm of Canterbury, Aurelius Augustine, Basil the Great, Bede, Robert Bellarmine, Bernard of Clairvaux, Bonaventure, John of Damascus, Dionysius the Areopagite, Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory of Nazianzus, Jerome of Stridon, Irenaeus of Lyon and others (Ushkalov, 1998, p. 34).

From the teachings of the Early Church Fathers, our Baroque writers borrowed the warning against putting too much trust in the power of the human mind. They were convinced that man was not given an ability or allowed by the Almighty God to comprehend the universe and the place of his own self in it, the laws of nature and existence, and even biblical truths, for these words are hidden and “sealed until the time of the end” (Daniel 12:4).

So, the truth is beyond reach. Nevertheless, people continued to search for it, often wandering through a great number of different, even opposing ideas and assumptions. Following this way, “Ukrainian writers, having subtly grasped the plot model, impress readers or listeners with unexpected associative discoveries, the search for hidden connections, and the originality of interpretations” (Matushek, 2000, p. 24).

The problem of interpreting the texts of the Holy Scriptures, started to be the subject for debate and sometimes even provoked heated discussions. According to Paul Ricoeur (1996), the concept of any interpretation really allows of different understanding, because interpretation is the work of thought, which is to transform the secret meanings into the revealed meanings, which shows the level of meanings included in the literal meaning. Symbol and interpretation must become correlative concepts; there is interpretation or ambiguity, and it is through interpretation that the ambiguity becomes clear.

Biblical hermeneutics was also based on the controversy over the ambiguity of multiple senses. Advocating for different ways of interpreting the Bible became one of the reasons for the split of the Church and the formation of numerous religious denominations.

The principles of biblical hermeneutics, having taken the place of the monolithic core of the form and content of literary texts, eventually began to go beyond the theological literature. Thus, the medieval interest in symbol and allegory led to the appearance of “empresas” – symbolic drawings that became fashionable at the royal courts of Europe in the fifteenth century. The Renaissance misunderstanding about the nature of Egyptian hieroglyphs, their perception as ideographic writing through which Egyptian priests expressed their wisdom, led to the appearance of emblems, allegorical prints with long explanatory verses, aimed at giving some moral lessons (Meid, 1974). The first collection of emblems was published by Alciato in 1531 (1531), and over the next two centuries a great number of emblematic collections appeared. It was believed that the emblem could communicate truth to the mind more directly than with the help of words. It was reflected in the mind, while the person’s gaze wandered through the symbolic details of the emblem. Thus, the Jesuits used the emblem as a powerful teaching tool. Moreover, for an educated person the universe seemed to be woven from emblems.

The Ukrainian Baroque writer Ioanykii Haliatovskyi expressed his views on the techniques of creating emblems in honour of the Virgin Mary in the book “Skarb pochwały”:

Tu ieszcze z pisma S. Zebranę, iako skarby kosztownę, do skarbnicy Naświętszey Bogarodźicy Jeleckiey dla iey pochwały przydane. Jeżeli czytelniku zácny masz Duchowne skárby, náuki wyzwolonę, do tych skárbów swoich otrzymasz ieszcze od skarbnicy Bogarodźicy Jeleckiey insze skarby duchowne. Emblemata. rozmáite, ktore malowáć álbo rysowáć należy. Namaluy sobie Kśięge, z napisem: Kśięga Rodzaiu, Iesusa Christusa (Mathei I.). Narysuy źwierćiádło z napisem: Zwierćiadło bez zmazy Boskiego Maiestatu (Sapien: 1.) Namaluy Tárcze, z napisem: Tarcza pomocy twoiey (Deuter: 33.). Narysuy Saydák z napisem w Saydaku swym skrył mię (Isay: 49.). Namáluy Gniázdo z napisem: ktoż wierzy temu, ktory gniazda niema (Jezus Syrach: 36.). Narysuy Oliwnę drzewo z napisem: Ia iestem iak Oliwa płodonosny w Domu Bożym (Psal: 51.). Namaluy Ogrod z napisem: Ogrod zamkniony Siostre moia (Cantic: 4.). Narysuy Studnia z napisem: Kto mnie napoi wodą z Studniey Berthlemskiey (I.Paralip: 11.). Namáluy VL, koło ktorego pszczoły látáią, z napisem: Ogarneli mię iako Pszczoły (Psalm: 117.). Narysuy Tęczę rożnemi fárbámi przyozdobioną z napisem: Tęcza była około stolicy, podobna widzeniem szmaragdowi (Apoc: 4.). Namaluy prześćiradło z Niebá zstępuiące do człowieka z napisem: Widźiałem Niebo odtworzone, y z stępuiące naczynie iakieś, iakoby przesciradło wielkie (Actor: 10.) Nárysuy Gołębice do Niebá lecęco, z napisem: przydż Gołębico moia (Cantic: 2.) (Galatowski, 1676, p. 14 (nn)).

An obvious manifestation of the emblematic thinking, characteristic of the Baroque authors, were engravings at the beginning of different structural parts of the text or inside them, which was a popular means of making the books more expressive during the Baroque period (Liamprekht, 2016). Thus, in the treatise “Nowa miara starey wiary” Lazar Baranovych put an engraving before the chapter “Bogаrodzico dziewico słoworodzico rodź y moie do ciebie słowo.” The picture represents the Virgin Mary weeping over Christ. It is accompanied by a quotation “Kto sądzi winnice, a z owocu iej nie pozywa” (Baranowicz, 1676c, p. 2 (verso)–3nn).

Grapes and vines were immensely popular plant symbols in the Baroque epoch. For the Jews, the grapes embodied the prospect for a new life. Meanwhile, for Christians, red wine made from grapes is a symbol of the Blood of Christ. Grapes are also a symbol of spiritual life, fertility, and rebirth. The vine is a symbol of Christ. A grapevine was the first one to be planted by Noah after the Flood. According to the Old Testament, the vine was brought to Moses from the Land of Canaan. So, it is also a symbol of the Promised Land. Ioanykii Haliatovskyi in his treatise “Messiasz Prawdziwy” interprets this symbol in the following way:

Bo ta żerdź znaczyła krzyż, grono winne znaczyło Chrystusa, który na krzyżu był przybity. Dwa mężowie znaczyli dwa zakony który szedł naprzód, znaczy Stary Zakon Moyzeszów, ktory szedł pozadzie, znaczy Nowy Zakon Chrystusów… Ziemią obiecaną nyzywa się Przeczysta Panna, patryarchom y prorokom obiecana, bo ona porodziła Chrystusa, ktory się gronem winnym y macicą winną nazywa (Galatowski, 1672, pp. 186–187).

Thus, the clearness and expressiveness of the visual image and the typological similarity of the situations of the birth of Christ – the Savior of the human race – of the Mother of God, and the appearance of the new green shoots grown from the vine symbolizing salvation – allow the author to apply these images to one of the main elements in honouring the Virgin Mary and Christ who have a special gift of protecting the human race from eternal and temporary grief. The use of this kind of emblem at the beginning of the book was supposed to show Baranovych’s devotion to the Mother of God. It should be mentioned that similar engravings also embellish the books “Skarb pochwały” (1676) and “Fundamenta” (1683) by Ioanykii Haliatovskyi.

Close in its meaning to the emblem is a symbol accompanied by only a short piece of writing. For example, these are popular images of “God’s face”, “God’s eye”, and “God’s hand” (prawica – the right hand). When Lazar Baranovych speaks about God’s right hand, which governs everything and saves everything in the stormy waves of the restless “sea of the world,” “Wiele na tym morzu potonęło, co się śmieło, bez tego wiosła, bez prawicy Pańskiey, ktorą tonącego Piotra ratowała, puśćili. Ieśli się łodką puśćisz na te morze, patrz ieśli masz takiego Styrnika, ktoremi wiatry y morze byli posłuszne” (Baranowicz, 1676c, p. 334), – this image embodies the Omnipresence of God, His benevolence, which, in turn, instils hope of salvation and reward for our life’s work that is eternal life. Similar to this metonymy are the images of “God’s ear” and “God’s eye,” which embody the omniscience of God, and finally the Holy Spirit that represents God’s Essence (Baranowicz, 1676b, p. 334).

.png)

Fig. 2. Drawings from “Księga śmierci” by L. Baranovych (1676).

Symbolic images are used to emphasize devotion and unshakable faith in God’s mercy. Here every part of the human body becomes its personification. In this way, Lazar Baranovych encodes in the picture the quote from the Gospel of Matthew, “Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened to you; For everyone who asks receives; the one who seeks finds; and to the one who knocks, the door will be opened” (Matthew 7:7–11), where the foot is a symbol of spiritual devotion and encounter with God, the hand is a symbol of activity; prayers and the mouth are symbols of the Word as the original source of life-affirming energy (Baranowicz, 1676b, p. 334).

..png)

Fig. 3. Drawings from “Księga śmierci” by L. Baranovych (1676).

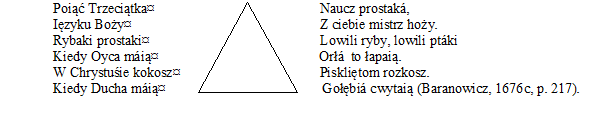

The symbolic meaning of the three hypostases of God, represented in the images of an eagle, a hen, and a dove, is also interpreted in the treatise “Nowa miara starey wiary” by Lazar Baranovych:

It is obvious that this epigrammatic poem by L. Baranovych is based on drawing parallels between the two worlds: the profane and sacred ones. The author calls the reader’s / listener’s attention to the impossibility of understanding the essence of God’s hypostases, but expresses the hope that “Ięzyk Boży” will teach even a simpleton (“prostak”) not only to comprehend the essence of the Trinity, but will also help to understand the meaning of the Leonine verse with a graphic image of a triangle. It should be noted that it was through the triangle that Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski (1958) represented the conceit visually: it was based on a theme, and the sides were opposite views. Thus, as a whole, it is the result of a combination of polar opposites. The hypostases of the Holy Trinity in the text possess the following characteristics: God the Father (the eagle) is characterized by strength, Christ (the hen) – by care and wisdom, the Holy Spirit (the dove) – by kindness and goodness.

A graphic image of a triangle can be also found in “Księga rodzaju” by Lazar Baranovych:

Geometric shapes were quite popular symbolic images during the period under discussion. For example, the emblem representing the world as a sphere is also characteristic of Baroque literature (Zosimova, 2008, p. 66). This image can be seen in the Polish play “The World Inside Out” by D. Nersesovych, where the figures of Ambition and Cupid try to change the direction of rotation of the allegorical sphere (Sofronova, 1981, p. 120). “The sphere of the world” is mentioned in the panegyric “Pełnia nieubywającej chwały...” by the Ukrainian Baroque author Stefan Yavorskyi (Jaworski, 1691, p. 14 (verso)). The sphere surmounted by a cross as an element of the coat of arms of the Ogiński family, represented in the engraving by Leontii Tarasevych (frontispiece of the book “Summaryusz cudowny łask… panny Maryey…”, 1686), symbolizes, according to D. Stepovyk (1986), the fleeting time and the transience of human life, contrasted with eternity. This interpretation is implied, in particular, by the famous Latin phrase written on the sphere, which is a quote from the seventh chapter of the Book of Job: “Militia (est) uita hominis super terram” (“Man’s life on earth is warfare (knightship)”, Job 7:1).

In one Polish-language Christmas drama put on at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy in the early 18th century, the Bride (the Pious Soul) gives little Jesus a rattle that is a hollow globe with pebbles inside. The bride sets the globe on a cross, as on a handle, and “shakes the little globe.” This bizarre baroque symbol, according to P. Lewin (1984), illustrates a set of ideas about the world as an idle, empty toy, the cross as the prefiguration of the Christ’s passion and the rattle as a whole as the reverse of one of the insignias of worldly rule, that is, the orb. It should be mentioned that at the very end of the Middle Ages the Christ child appeared in Christian art with the globus cruciger (“the orb and cross”) in his hand. “The Baroque era,” the researcher says, “went even further: not only is the world, seemingly ruled by powerful men, actually in God’s hands, but to him it is no more than an idle, empty toy, handled by his cross” (Lewin, 1984, p. 102). This image of the Saviour was widely employed in various genres of European Baroque art, for example in Polish Christmas poetry: “Ucieszna Panno, pokaż nam Syna / Który w swych palcach krąg ziemie trzyma” (Sokołowska and Żukowska, 1965, p. 133).

Conclusions

Thus, many literary works of the 17th century show the influence of the emblem on the formation of symbolic representation, arranged to reveal the truth implicitly or explicitly through the sequential placement of the elements. Many poetic images of the seventeenth century come from well-known emblems, but as a whole they often represent a common style of thinking, developed due to constant reference to emblem books and the use of the profane material within the doctrine, which followed the patterns and techniques of preaching, characteristic of medieval priests, especially the Franciscans.

Emblems, symbols, and hieroglyphs were means of perceiving, interpreting, and opening the world of the Bible to the Baroque reader. They were also widely used in literary theory courses as means of depicting the surrounding reality.

The Baroque epoch, combining the traditions of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, provided fertile ground for the development of four-sense biblical hermeneutics as one of the key components of the poetics of Old Ukrainian literature, and later – as a philosophical category.