Hunting Practices Among the Indigenous “Truká” in the Semiarid Region of Brazil

Prácticas de caza entre los indígenas "Truká" en la región semiárida de Brasil

Abstract

This paper aims to provide information on hunting in the Semi-arid Northeast counting the hunting practices of the Truká Indigenous people. These pieces of information were obtained through interviews, using semi-structured questionnaires with fifty-five Indigenous hunters, distributed in four Truká villages located in the states of Bahia and Pernambuco. Thirty-nine poultries, thirteen mammals, and seven reptiles commonly captured the Truká have been cited. Out of the total number, forty-five (42.3%) were used for feeding. Species used as pets (n=20), in magic rituals (n=1), in traditional medicine (n=11), in local handicraft (n=23) and in control hunting (n=6) have also been quoted. Among those species, only one is listed as endangered, to say, Anodorhynchus leari, and one vulnerable, Leopardus tigrinus. Among the interviewees, the common hunting techniques are trap, hatch, pitfall, lasso, hunting net, rifle, slingshot, hook, besides handgrip and dog hunting. The awareness of local perception in the usage of wild fauna is fundamental for decision making in the elaboration of projects for the conservation and management of local fauna, aiming both the maintenance and the continuity of access to this natural resource.

Keywords

Game Fauna. Indigenous Subsistence. Biodiversity Conservation

Resumen

Este documento tiene como objetivo proporcionar información sobre la caza en el noreste semiárido contando las prácticas de caza de los indígenas Truká. Estos datos se obtuvieron a través de entrevistas, utilizando cuestionarios semiestructurados con cincuenta y cinco cazadores indígenas, distribuidos en cuatro aldeas Truká ubicadas en los estados de Bahía y Pernambuco. Se han citado treinta y nueve aves de corral, trece mamíferos y siete reptiles que capturaron comúnmente a Truká. Del total, cuarenta y cinco (42.3%) se utilizaron para alimentarse. También se han citado especies utilizadas como mascotas (n = 20), en rituales mágicos (n = 1), en medicina tradicional (n = 11), en artesanía local (n = 23) y en caza de control (n = 6). Entre esas especies, solo una figura en peligro de extinción, por ejemplo, Anodorhynchus leari, y una vulnerable, Leopardus tigrinus. Entre los entrevistados, las técnicas de caza comunes son trampa, escotilla, trampa, lazo, red de caza, rifle, tirachinas, anzuelo, además de la empuñadura y la caza de perros. La conciencia de la percepción local en el uso de la fauna silvestre es fundamental para la toma de decisiones en la elaboración de proyectos para la conservación y el manejo de la fauna local, con el objetivo tanto del mantenimiento como de la continuidad del acceso a este recurso natural.

Palabras clave

Juego Fauna. Subsistencia Indígena. Conservación de la Biodiversidad

Introduction

Throughout history, it has always been possible to observe the different forms of interaction between humans and fauna. These forms of variation range from interaction for feeding until the usage for symbolism purposes (Nóbrega et al., 2011). Regardless of the communication, catching wild animals are shown to be the first form of synergy between animals and people (Alves, 2012). Alves and Souto (2010) attest that human cultures have developed different forms and strategies of hunting, a practice persistent to a greater or lesser degree in all human populations until now (Alves, 2012; Alves and Souto, 2015; Martins, 1993; Freshman, 1995; Leeuwenberg and Robinson, 1999).

Several authors point out that hunting has been fundamental for the maintenance of culture; besides, it is a source of protein in several populations, mainly in traditional communities that still maintain intense contact with wild resources (Lourival and Fonseca, 1997; Redford, 1997; Peres, 2000a; Figueira et al., 2003; Milner-Gulland and Bennett, 2003).

Among the traditional communities in Brazil, Indigenous peoples represent an essential ethnic group in which wild animal hunting is maintained (Luciano, 2006). Thus, investigating Indigenous knowledge concerning wildlife is one of the focuses of Ethnozoology (Alves and Souto, 2015; Overal, 1990; Marques, 2002). Ethnozoological research helps us to understand the species that local populations are exploiting and how these practices have changed over the years, as well as the factors that influence these changes (Alves, 2012; Alves and Souto, 2015). This information is fundamental in the search of strategies aiming the sustainable exploitation of fauna (Alves, 2012), especially amongst traditional Indigenous communities, which exploit animals, causing less impact than non-traditional populations.

In Brazil, Ethnozoological studies have been published showing hunting an activity in rural, urban, and traditional communities (Alves and Souto, 2011). The clandestine or semi-clandestine character associated with the capture and trade of wild animals is one of the factors that positively contributes to the scarcity of research on these topics (Alves et al., 2009b; Alves and Souto, 2011).

It is worth mentioning that hunting of wild animals is a prohibited activity all over the Brazilian territory, according to the Law of Fauna Protection No. 5.197/1967. However, in the Indigenous lands, according to Law no. 6001/1973, 24, § 2, “the Indian is guaranteed the exercise of hunting and fishing in the areas occupied by them”, because it is understood that the capacity of self-support of the Indigenous peoples is in the deep interdependence that they maintain with nature. One of the essential characteristics of the Indigenous culture is that they are focused on supplying the physical, social, and spiritual needs of the people. These activities are primarily focused on hunting, fishing, gathering, and handicraft (Luciano, 2006).

Despite the cultural and nutritional importance of hunting, we highlight this activity can influence the population’s density of exploited species. It may represent a factor causing population decline or extinction (Altrichter, 2005; Chiarello, 2000; Fachín-Terán et al., 2004; Naranjo et al., 2004; Peres, 2000a; 2001; Thiollay, 2005; Thoisy et al., 2005). Knowing the species of fauna hunted, their form of capture, the quantity, and the reason for extraction, all this is fundamental to understand the consequences of hunting wild animals in natural environments (Alves, 2012; Trinca, 2004).

The importance of hunting and use of wild fauna is well evidenced in areas such as the Semi-arid region of Brazil, which is home to a population of about 25 million (INSA, 2010), of which about 350,000 are Indigenous (IBGE, 2010) and use wild fauna for various purposes.

Among the Indigenous living there, we can find the Trukás, an ethnic group distributed in four villages linked by cultural, religious, and social traditions (Batista, 2005). Considering two of the Trukás communities located near the São Francisco River and the other two more distant, hunting activities are expected to have been influenced by the physical environment. From this perspective, this study aimed to provide information on hunting and use of fauna in the Semi-arid Northeast based on hunting practices of the Truká Indigenous people. Its importance was addressed by characterizing the socio-cultural context in which these resources are used. Similarly, the captured species and the influence of migration and socioeconomic variables on the use of hunting species were recorded.

Answers to the following questions were sought: (1) migration process changes the wealth of animal species used by people with common origin (2) use of animal products are modified by migration (3) Indians living in locations geographically close to the center of origin tend to present a more significant similarity concerning animal species and their uses, (5) socioeconomic aspects of the interviewees, such as age, income, and education, influence the knowledge about the resources of animal origin, and (6) there is a difference between men and women with the knowledge of wildlife.

Methodology

Field of study and the Truká Indians.

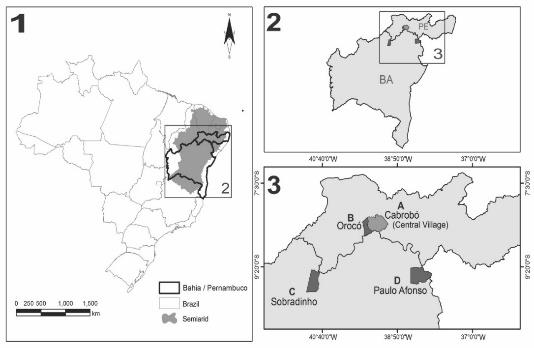

The Truká people live in four villages located in the Sub-median São Francisco River, in the Semiarid region of Northeast Brazil (Fig. 1), the Mother Village on the Island of Assunção, municipality of Cabrobó (8º 31’ 07,11’’ S x 39º 22’ 20,87’’ W); Tapera village, municipality of Orocó (8º 36’ 24,4’’ S x 39º 34’ 54,9’’ W), both in the State of Pernambuco; Camixá village in APA do Lago de Sobradinho-BA (9º 29’ 47,7’’ S x 40º 51’ 07,9’’ W) and Tupan village, municipality of Paulo Afonso-BA (9º 25’ 10,58’’ S x 38º 16’ 31,05’’ W).

Figure 1. Location of the semi-arid cities where Truká villages are located.

Source: Santos et al. 2016.

The towns of Orocó and Cabrobó are located in the São Francisco Meso-region and the Petrolina Micro-region of the State of Pernambuco. The vegetation is composed of Hyperxerophilous Caatinga with sections of Caducifolic Forest. The climate is of the Semi-arid Tropical type (SGB, 2005a; 2005b).

The towns of Sobradinho and Paulo Afonso, both in the State of Bahia, are inserted in the Drought

Polygon with Semi-arid and Arid climate type and average annual temperature of 27º. The predominant vegetation is the open or dense Caatinga type with or without palm trees (SGB, 2005c; 2005d).

Data collection

Sampling was of the intentional non-probabilistic type (Albuquerque et al., 2014; Spata, 2005), using the ‘snowball technique’ (Bailey, 1994) to locate possible respondents.

Information on the capture and use of animals was obtained through interviews using semi-structured questionnaires (Albuquerque et al., 2014; Huntington, 2000; Mello, 1996). The questionnaires contained issues about use of each animal, place of collection, equipment used in the capture, changes in fauna populations over time, type of use, and others involving socioeconomic aspects of the interviewees to understand their influence on the use of wildlife.

The common names of the species were recorded as cited by the people interviewed. The animals were identified with the help of specialists in the following ways: 1) analysis of photographs of the animals and 2) through the common names, with the help of taxonomists familiar with the fauna of the study areas.

Ethical and legal aspects

Considering the ethical aspects, at the beginning of each interview, the objectives of the present study were explained to the interviewees, and permission was requested to record the information by presenting and signing the informed consent form (TCLE) and the consent form for image use. Authorization for access to traditional knowledge associated with genetic heritage was obtained from the Committee of Ethics in Research (Opinion No. 723,750), the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage (Case No. 013/2013. Case No. 01450,010527/2013-30). The authorization for entry into Indigenous lands was granted by the National Indian Foundation, through the Regional Coordination of Lower São Francisco River through the Letter of Consent dated July 23, 2013.

Analyses of data

Incidence matrices (use/non-use) of zootherapeutic species were developed for each village with the help of LibreOffice Calc v. 4.2 software, built with the combined information from all localities. From these matrices, EstimateS v. 8.2 (Colwell, 2009) was used to calculate the Chao 2 estimator values, with 1000 randomizations without replacement of the sample sequences. Species accumulation curves were elaborated with the values of the Sobs obtained, and the wealth estimated by Chao 2 95% confidence intervals of Chao 2 and Sobs were used in plotting the curves.

Non-parametric tests for statistical comparisons were performed using the software Program R. The Mann-Whitney U test (Mann and Whitney, 1947) was applied to verify if there is a difference between the number of species used by men and women. The Kruskal-Wallis H test (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952; 1953) was used to check if there is a difference in the number of species used according to the variables age, income, and education. For both tests, the 5% probability level was adopted.

The similarities of the faunistic resources used in the studied sites were obtained through Jaccard’s similarity coefficient, which was calculated through Primer 6 software, based on the presence/absence matrix of the species explored per studied area. The distances between the communities were represented in dendograms.

Results and Discussion

Socioeconomic profile of respondents

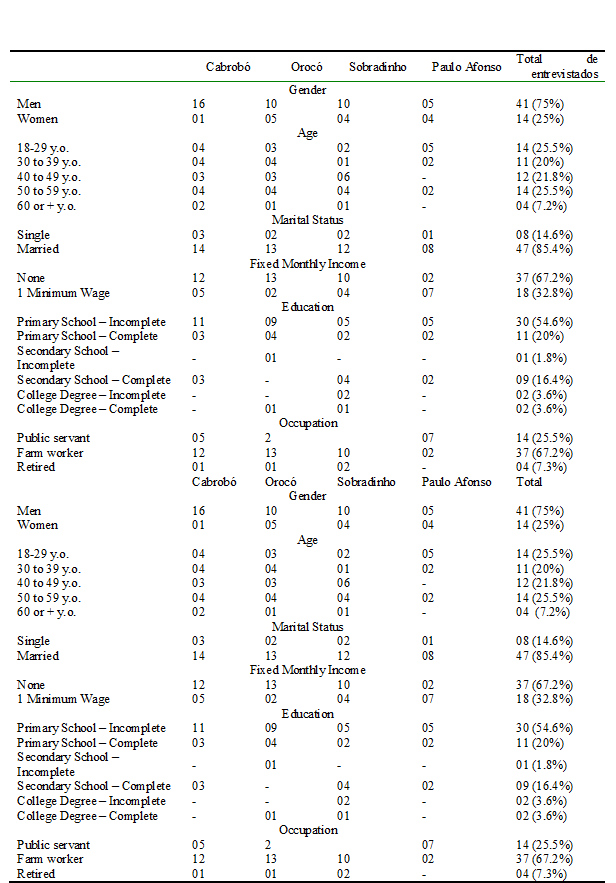

The information was obtained from fifty-five Indigenous Truká hunters, aged eighteen years or more, in the four locations surveyed, seventeen in the village of Cabrobó; fifteen in Orocó; fourteen in Sobradinho; nine in Paulo Afonso. The socioeconomic information of interviewees was accessed through a structured questionnaire. The socioeconomic profile is presented in Table 1.

Species richness

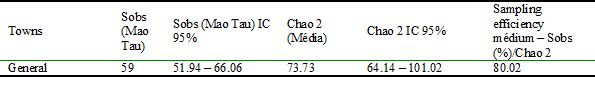

Considering the villages surveyed, interviewees cited fifty-nine animal species, distributed among thirty-nine families. We observe in Table 2 that the estimator Chao 2 indicated average wealth estimated at 73.73 species, with confidence intervals ranging from 64.14 to 101.02 species.

Table 2.

Total richness of species hunted in Truká villages recorded and estimated by the non-parametric estimator Chao 2, plus the average sample effort.

Chao 2 suggests that, on average, the sample efficiency was 80.02% (Sobs/Chao 2). Observing the general species accumulation curve (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. General species accumulation curve (Sobs / Chao 2).

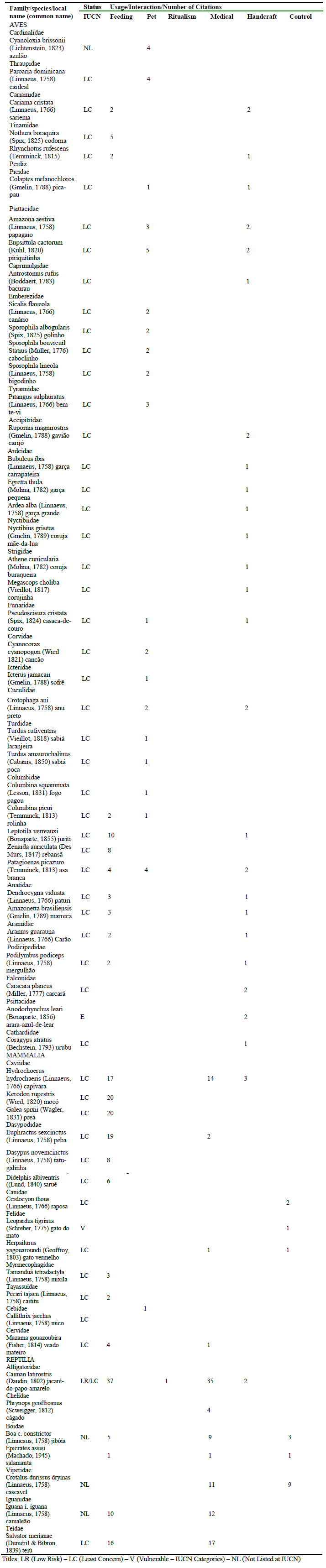

The mentioned species are distributed among the following taxonomic categories: birds (n=39), followed by mammals (n=13), and reptiles (n=7) (Table 3). These vertebrates were mentioned in the following categories regarding their use: feeding (25 species = 42.3%), estimation (20 species = 33.8%)), magical-religious (1 species = 1.6%), medicinal (11 species = 18.7%) and artisanal (26 species = 44.1%). Besides the uses, some animal species mentioned are slaughtered for control (6 species = 10.2%) because they represent risks to the breeding of domestic animals such as goats, sheep, and chickens.

The same species can be used for multiple purposes, which enhances its use. Thus, an animal slaughtered for feeding purposes may have its parts or inedible products used for other purposes. As a result, there is a reduction in the number of individuals slaughtered, which contributes to the conservation of game species.

The vertebrate species hunted by the Truká people resemble what has been observed among

non-indigenous hunters in the semi-arid region of Brazil, as previous studies point out (Alves et al., 2009a; 2012a; Fernandes-Ferreira et al., 2012). It

shows the importance of fauna for several rural and traditional communities in Brazil.

Among the most hunted mammal species for the caatinga region, the armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) and (Euphractus sexcinctus) stand out (Alves et al., 2009a; Barbosa et al., 2011; Dantas et al., 2011), among the most cited by Truká hunters.

Despite the hunting preference for mammals, when considering the richness of species used as food, birds represent the group with the highest number of citations by the Truká people, especially hummingbirds and tinamids (Alves et al., 2012a; 2013a; Bezerra et al., 2011; 2012a;

2012b).

The representativeness of birds becomes more evident when we consider the high frequency of wild birds cited as pets, revealing that this reality

involves Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities living in the Semi-arid.

Several authors point out this is a strong factor stimulating the illegal trade of birds in the caatinga (Rocha et al., 2006; Alves et al., 2013a; Licarião et al., 2013). In several cities of the northeast interior, there are public and free markets where wild animals are traded, especially poultry (Alves et al., 2013b).

In the case of the researched area, inserted in the Caatinga biome, bird richness is estimated at 510 species (Silva et al., 2003) concerning mammals with about 143 registered species (Oliveira et al., 2003). The bird species richness in the caatinga is a factor that positively contributes to a more significant number of locally hunted bird species (Albuquerque et al., 2012).

Among the reptiles, we recorded the hunt of seven species, belonging to six families. It is the most significant number of citations and uses for the yellow-footed caiman (Caiman latirostris). Several studies have recorded the hunting of this species as well as its use in the Semi-arid northeast, especially in areas of occurrence of the species (Costa-Neto, 2000; Fernandes-Ferreira et al., 2013; Alves et al., 2009c; Alves and Alves, 2011). Among the Trukás, the yellow-footed caiman is widely used in traditional medicine (Santos et al., 2016).

Concerning mammals, thirteen species belonging to eight families were recorded, the families Caviidae and Dasypodidae, the most representatives with three species each (Table 3). The species with the highest number of citations was the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), a semi-aquatic species found on the banks of the São Francisco River, in areas easily accessible to hunters. The hunting records of this species are shared among traditional communities in the Amazon, among them the Macuxi Indians (Mesquita and Barreto, 2015; Redford and Robinson, 1987; Peres 2000a; 2000b; Rosas and Drummond, 2007; Sampaio, 2007; Strong et al., 2010).

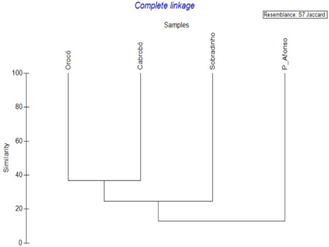

Regarding the hunting patterns of the Truká people, the similarity analysis showed similarities between the four villages, with Aldeia Mãe (Cabrobó) and Village Orocó (J=0.38), being more similar, possibly because they are closer, both located on the banks of the São Francisco River in the state of Pernambuco.

Regarding the other two villages located in Bahia, Sobradinho has more similarity with the group formed by the towns of Cabrobó and Orocó (J=0.25), and the town of Paulo Afonso has more similarity with the group formed by the villages of Sobradinho and Cabrobó (J=0.15), and other communities (Fig. 3).

Geographic and environmental factors may be influencing the similarities between the Truká Orocó and Cabrobó villages, both geologically inserted in the Borborema Province, in the São Francisco Sub-medium region, under close environmental conditions (SGB, 205a; 2055b).

The towns of Sobradinho and Paulo Afonso are located in the so-called Drought Polygon, with vegetation of Caatinga with distinct physiognomies of the towns in Pernambuco (SGB, 2005c, 2005d).

It should also be noted that the first group villages are located on the fluvial islands of the São Francisco River. Therefore, the access to aquatic animals is more significant when compared to the towns of the second group. In this situation, it was not surprising that aquatic or semi-aquatic animals such as the caiman (Caiman latirostris), the terrapin (Phrynops geoffroanus), and the capybara (Hidrochaerus hidrochaeris), were mentioned more frequently in the towns of Cabrobó and Orocó. It reflects the bond between the towns and types of habitat in the study region.

Figure 3. Grouping analysis using Jaccard’s similarity index of the richness of species hunted in the four Truká villages.

These results suggest that the composition of local fauna influences the selection of wild animal species targeted for hunting and used by people for various purposes, as indicated by previous research (Alves and Rosa 2006; Alves et al., 2007; 2009a; 2012c).

In another perspective, results suggest that migrants from the Truká people have been adapting to the availability of animals in the new localities where they have settled. It may have resulted in the abandonment of the use of species more difficult to access, such as aquatic and semi-aquatic species, also allowing the incorporation of new species available more quickly in the new environment occupied.

Table 3.

Species of game vertebrates used by indigenous hunters in the semi-arid region of Bahia and Pernambuco; their forms of use and interaction with the local population.

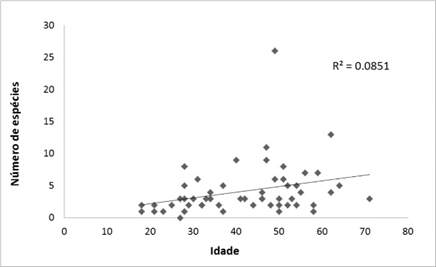

Our results revealed that there was no significant difference between the number of species cited by women and men in all communities surveyed (Mann-Whitney U = 223.5, p-value = 0.2166).

This difference can be explained by the significant number of male hunters concerning women, or by the social role of men and women in the Truká culture. Men are focused on the activities that generate the livelihood of families, and women on domestic operations, previous corroborating studies (see Torres-Ávila et al., 2014).

No significant difference was observed between the age of interviewees and the number of species cited (R2 = 0.0851). Regarding the income range, there was also no significant variance regarding the number of species mentioned in the two income groups (Kruskal-Wallis: H = 0.0040617; df = 1; p-value = 0.9492).

No significant difference was found (Kruskal-Wallis: H = 3.4855; df = 5; p-value = 0. 6256), among the number of species mentioned by the interviewees in relation to the level of schooling in the four locations (Table 1) (1 – Primary School Incomplete (n=30); 2 – Complete Primary School (n=11); 3 – Incomplete Secondary School (n=1); 4 – Complete Secondary School (n=9); 5 – Incomplete College Degree (n=2).

Accordingly, it is found that socioeconomic factors do not influence the number of species known as potentially hunted, highlighting the strong tradition of hunting activities among the Truká, practiced by Indians of different profiles.

Only concerning gender, as it was expected, men have more excellent knowledge about the hunted species since hunting is a practice mostly exerted by males, It comes to be a similar situation that occurs in other locations in Brazil, whether in Indigenous communities, or not (Becker, 1981; Miranda and Alencar, 2007; Alves et al., 2009a; Hanazaki et al., 2009; Souza and Alves, 2014).

Vertebrates used in food by the Truká people

Feeding was the primary use of the species cited by the informants (n = 25 / 42.3 %). Among the mammals used as food by Indigenous Truká hunters are Kerodon rupestrian (n=20), Galea spixii (n=20), and Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris (n= 17), Euphractus sexcinctus (n=19) and Dasypus novemcinctus (n=8).

Among birds mentioned, we highlight the juriti (Leptotila verreauxi) (n=10), and the flock, Zenaida auriculata (n=8), and flocks in feeding were recorded by Barbosa et al., 2010.

The most cited reptiles for food use were Caiman latirostris (n=37), Salvator merianae (n=16), and Iguana (n=10), which have their consumption recorded in rural and urban areas in Brazil (Alves et al., 2009a; 2012b; 2012c; Fernandes-Ferreira et al. 2013).

Creation of wild fauna

In Brazil, the creation of wildlife species as pets is a traditional practice, occurring from large urban centers to isolated communities, being very frequent in the semi-arid northeast (Alves et al., 2010b; 2012c; Bezerra et al., 2011; 2012b).

Among the Trukás, poultries are the preferred species used as pets (Fig. 4), highlighting the Thraupidae family with the highest number of species cited (n=8), followed by the Columbidae family (n=6), corroborating studies conducted in the semi-arid region of the northeast (Alves et al., 2012a; 2010a; Rocha et al., 2006; Santos et al., 2012; Fernandes-Ferreira et al., 2011) and in other locations in Brazil (Pereira and Brito, 2005; Ferreira and Glock, 2006; Araújo et al., 2010; Alves et al., 2012c).

Besides wild birds, only one species of wild vertebrate was mentioned as a pet, the primate Callithrix jacchus (Fig. 4), considered docile, being raised freely in the domestic environment with children. Recent studies report the breeding of this species in the domestic environment (Aguiar et al., 2011; 2012).

Figure 4. A = Turquoise-fronted amazon (Amazona aestiva); B = Picazuro pigeon (Patagioenas picazuro); C = White-naped jay (Cyanocorax cyanopogon); D = Campo troupial (Icterus jamacaii); E = White-throated seedeater (Sporophila albogularis); F = Common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus).

Magical-religious rituals

Studies point to the use of wild animals in Brazil religious rituals in practices related to Afro-Brazilian religions (Léo Neto et al., 2009; Alves et al., 2012c; Prandi, 1996; Baptista, 2008) and among Indigenous peoples (Zannoni, 2008).

Set in the context of ethnic-racial religious manifestations, the African religions have a peculiar dogmatic element, the sacralization of animals also called ritual sacrifice (Lima and Oliveira, 2015).

This practice is not exclusive to the African matrix religions; it is historically, currently active in various religious confessions (Robert et al., 2008). Zannoni (2008) recorded among the Tenetehara Indians the practice of hunting animals for celebrations.

In several Indigenous nations, life and existence are impregnated with a sense of the sacred. The Indigenous religion receives influence from the beliefs of the Christian matrix and African matrix, as well as influences (Rodrigues and Vilarino, 2011).

Therefore, the use of animals in magical-religious rituals has been recorded in the literature (Zannoni, 1999; 2008). Among the Trukás, the Pajés determine the magical and ritualistic use of animals.

In the researched areas, the only wild species registered for ritual use was the caiman (Caiman latirostris). The form and purpose of the application are not revealed to Non-Indigenous people. As they are aware, it is part of the universe of Indigenous science, experience restricted to the religious leaders of the Truká people.

Medical Fauna

The species used by the Truká Indians for medicinal purposes were recorded in other Ethnozoological studies focusing on Zootherapy among Indigenous peoples in Northeastern Brazil (Bandeira, 1972; Lima and Santos, 2010; Pereira and Schiavetti, 2010; Costa-Neto, 1999) and among Non-Indigenous populations (Alves et al., 2007; 2009b; 2009c; Costa-Neto and Alves, 2010; Alves and Alves, 2011).

Reptiles were the most cited animals for medicinal use, an expected result, being used in popular medicine by several traditional communities in Northeastern Brazil (Alves and Pereira-Filho, 2007; Alves et al., 2010c; 2012a).

Among the registered species, Caiman latirostris, Salvator merianae, Crotalus durissus, Iguana iguana and Boa constrictor are among the most commonly used animals in Brazilian popular medicine; recent studies have investigated the efficacy of medicinal use of these species (Ferreira et al., 2009; 2010; 2011; 2014).

Handicraft

By-products of some of the species mentioned have been used for making handicrafts such as feathers, teeth, and bones (Fig. 5). The most used species are birds (n=26), whose feathers are used in the making of necklaces, earrings, cocares (headdresses), and ornamentation of ritual instruments such as the maraca.

Besides birds, the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) and the caiman (Caiman latirostris) have their bones and teeth used for making handicrafts. The use of animal by-products in the production of ornaments among Indigenous people is described in previous studies (Dorta and Velthem, 1980; Nicola and Dorta, 1982; Dorta, 1986; Ribeiro, 1986; 1988; Almeida et al., 2006).

Among the Truká, six species are hunted as a mean of control, as they are perceived as harmful animals. Among mammals, the fox (Cerdocyon thous), the wild cat (Leopardus tigrinus) and the red cat (Herpailurus yagouaroundi) cause losses to domestic animal breeders. Among the reptiles, the boa constrictor (Boa constrictor), rattlesnake (Crotalus durissus), and the salamant (Epicrates assisi) were mentioned, as they are considered potentially dangerous.

Figure 5. A = Headband with hawk feathers (Rupornis magnirostris); B = Little egret (Egretta thula); C = Carcara feathers (Caracara plancus); D = Necklace with bacurau feather (Antrostomus rufus); E = Earring with parrot feathers (Amazona aestiva); F = Necklace with capybara bones (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris).

Although the main reason for slaughtering these species is control, by-products derived from them are used for other purposes, and for example the snake lard is used in the traditional local medicine.

The slaying of wild fauna as a form of control because it represents danger or harm to traditional populations, as reported in communities in the Semi-arid Northeast (Mendonça et al., 2011; Alves et al., 2012a; 2012b; 2012d; Barbosa et al., 2011), and in other regions of Brazil (Ferreira et al., 2012b).

Capture techniques

Ten hunting techniques were cited by the interviewees (Fig. 6): trap, hatch, pitfall, lasso, hunting net, rifle, slingshot, hook, besides handgrip and dog hunting. These techniques were recorded in other locations in the Semiarid (Alves et al., 2009a; Bezerra et al., 2011; 2012a). The poultries are caught with trap, slingshot, and handgrip (in the nests). For the capture of mammals, lasso, net, rifle, slingshot, hatch and dog hunting, a technique also used to catch reptiles, added by hook to catch alligators. No variations were recorded in the capture techniques between villages.

Figure 6. A = Trap; B = Lead-shotgun; C = Slingshot; D = Trap; E = Booby trap; F = Hook.

Conservationist implications

Out of the species recorded in this research, the hen armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), mocó (Kerodon rupestris), bush cat (Leopardus tigrinus), red cat (Herpailurus yagouaroundi) and the blue-necked macaw (Anodorhynchus leari) are on the Brazilian list of endangered fauna (Ministry of the Environment, 2014).

Only the bush cat and the blue macaw appear vulnerable and threatened on the list of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2015). The other species are classified as low levels of concern or do not appear on the endangered species list.

In Truká society, like other indigenous peoples, the search for and capture specimens are guided by the people’s ancestral spirits (Zannoni, 1999; 2008). Because of this belief, the practice of hunting is not recommended by indigenous religious leaders for any individual, as it represents a ritual of the Truká tradition, and practitioners must be prepared by indigenous science to practice it. According to an interviewee’s statement: “Hunting takes place all year round, but we need to ask permission from ‘Mãe-da-Mata’, our light charm, and she can only take what she allows. Otherwise, she will whip us in the woods. When she hears the whistle, it’s time to run away, the hunter who punishes ‘Mãe-da-Mata’ too much, can only take what he is going to eat out of the woods” (Truká Hunter).

Most Truká hunters have noticed the population decline of some species over time in the areas of this study. As Leal et al. (2005) point out, not only the hunting of wild animals but also activities that provide the continuous removal of vegetation from the Caatinga, have led to the impoverishment of the Caatinga biodiversity.

Hunting and wildlife use is an old practice among Truká and persists in all villages formed from their center of origin. For Alves et al. (2010b), the persistence of hunting activities in Brazil, despite illegality, is closely associated with cultural issues.

In Indigenous territories, the free exercise of hunting is guaranteed (Law 6001/1973), and no surveillance can be carried out to curb or minimize this practice. From this perspective, research in Indigenous societies offers a unique opportunity for the evaluation of hunting pressure, through the monitoring of hunters and quantification of the most hunted species.

It may contribute to the elaboration of management plans, aiming at the conservation of animals, thus guaranteeing the survival of exploited species and the maintenance of exploitation and culture by traditional communities.

It should be noted that the indigenous societies that live in areas of caatinga, like the Trukás, have a cultural relationship that involves feelings and beliefs that mediate the relations of the people with the local fauna, thus ensuring less hunting pressure on native animal populations.

As an example, the informants point out that in the period between October and March, the breeding season of the capybara, during this period, the captured females and puppies are returned to the environment.

A similar attitude was described by Pereira and Schiavetti (2010), with the Tupinambás de Olivença Indians. To compensate for the absence of game meat, the Trukás Indians dedicate themselves to raising domestic animals (see Chapter 2 – Santos et al., 2016), and eventually to fishing and raising fish in captivity (see Chapter 3 – Santos and Alves, 2016). It is thus evident that discussing the educational use of animals within the cultural perspective of people who exploit animal resources is an essential step towards achieving sustainability.

Final Considerations

The use of wild fauna by Indigenous peoples located in the semi-arid region of the Brazilian Northeast represents the cultural practice of these populations, and hunting in their territories is ensured by specific legislation that guarantees the maintenance of this tradition.

Data reveal that the migrant groups have not abandoned the practice of hunting, a cultural trait of the Truká people, but have adjusted these cultural practices to the wildlife existing in the new environment occupied, similar to the use of zootherapies by the communities studied here (see Chapter 2). Santos et al. (2016) corroborate previous studies that focus on the maintenance of natural resource use by migrant communities.

This way, the migrant communities of the Truká people keep on re-signifying their knowledge and maintaining their cultural traditions, like the Village Mother of Cabrobó (their place of origin) that use captured species primarily in food. The culture of raising species of wild fauna remains in the domestic environment, in addition to the use of by-products of animals slaughtered in traditional medicine, religious rituals, as well as local handicrafts. Occasionally, it occurs the slaughter of species for control, because they cause damage to man or are considered harmful to man and domestic animals.

However, the flesh of wild animals is no longer the primary source of animal protein since Truká are breeders of animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep, goat and a variety of poultry, which also favors the conservation of wild species. Suffice to say, Truká hunters recognize that the removal of vegetation by Non-Indigenous invaders, directly and indirectly, affects the availability of animals. This information should be taken into account when designing projects aimed not only at the maintenance of fauna but also at the continuity of access to these resources, which ultimately favors the preservation of the culture of indigenous peoples in the region.