Self-efficacy Sources among General Education Teachers in Inclusive Schools: A Cross-Cultural Study

Fuentes de autoeficacia entre maestros de educación general en escuelas inclusivas: un estudio intercultural

Abstract

The inclusion of students with special needs in general education classes has become a goal that all educational systems worldwide strive to achieve it. The inclusion of special needs has many benefits, whether for special needs students or regular students. The current study aims to reveal the differences in the self-efficacy among general education teachers in both the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Arab Republic of Egypt. It aims also to reveal the sources of this self-efficacy in both countries. The core study sample consisted of (96) Saudi teachers and (88) Egyptian teachers. The researcher used the teachers 'self-efficacy scale and the teachers' self-efficacy sources scale. The results of the study indicated that there is a significant difference between the average scores of the total self-efficacy and its sub-dimensions between the Saudi and Egyptian sample for the outperform of The Egyptian teachers. It indicated that the source of the mastery experience was a significant predictive of the self-efficacy of the Saudi teachers, and it explained 53% of the variation in self-efficacy. It also indicated that the mastery experience was a significant predictive of the self-efficacy of the Egyptian teachers, and it explained 13% of the variance in self-efficacy.

keywords

alternative experiences, Inclusion, mastery experiences, self-efficacy, verbal persuasion

Resumen

La inclusión de estudiantes con necesidades especiales en las clases de educación general se ha convertido en un objetivo que todos los sistemas educativos del mundo se esfuerzan por lograr. La inclusión de necesidades especiales tiene muchos beneficios, ya sea para estudiantes con necesidades especiales o estudiantes regulares. El presente estudio tiene como objetivo revelar las diferencias en la autoeficacia entre los maestros de educación general tanto en el Reino de Arabia Saudita como en la República Árabe de Egipto. Su objetivo también es revelar las fuentes de esta autoeficacia en ambos países. La muestra central del estudio consistió en (96) maestros sauditas y (88) maestros egipcios. El investigador utilizó la escala de autoeficacia de los docentes y la escala de fuentes de autoeficacia de los docentes. Los resultados del estudio indicaron que existe una diferencia significativa entre los puntajes promedio de la autoeficacia total y sus subdimensiones entre la muestra saudita y egipcia para el mejor desempeño de los maestros egipcios. Indicó que la fuente de la experiencia de dominio fue un predictor significativo de la autoeficacia de los maestros sauditas, y explicó el 53% de la variación en la autoeficacia. También indicó que la experiencia de dominio fue un predictor significativo de la autoeficacia de los maestros egipcios, y explicó el 13% de la variación en la autoeficacia.

Palabras clave

experiencias alternativas, inclusión, experiencias de dominio, autoeficacia, Persuasión verbal

Introduction

The trend towards developing national education systems that embrace inclusion around the world has increased since the publication of the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Education for People with Special Needs (UNESCO,1994). This trend has been further reinforced by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly, 2015) that considers inclusive education a global goal to achieve human rights principles. Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Special Needs affirms not only the right to education but also a "comprehensive education system at all levels" by the end of 2015, which has been ratified by most countries around the world.

Inclusive education is defined as "the ability of the educational system to provide the necessary academic and behavioral support to all students, regardless of disability or difference (i.e. gender, race, location or language), to participate and succeed in scholastic academic, Social, methodological and extracurricular activities alongside their peers " (Parnell, 2017, p.3). Inclusion exceed geographical change in the classroom and includes a distinct mindset that focuses on the abilities and needs of all students in the classroom (UNESCO, 1994). Inclusion has benefits that include both regular students and with special needs students. It was found that students with special needs who receive inclusive education have obtained better educational and social outcomes (Rujis & Peetsma, 2009). For regular students, there have been improvements in social skills and tolerance towards their special needs peers (Kalambouka, Farrell, Dyson, & Kaplan, 2007). This is confirmed by recent literature reviews that indicate the effectiveness of inclusion in the social and academic outcomes of all students, not just students with special needs (Black-Hawkins, 2010; Hehir et al. 2017; Rose, Gravel & Gordon, 2014).

The past three decades have witnessed an important educational reforms in relation to students with special needs. These students were previously taught in separate schools, but large numbers of students with special needs are now taught regularly in public education schools. The composition of the general education school classes in a certain countries of the world, like Canada and the United States of America, has changed dramatically. 96% of regular school teachers in the United States of America indicated that there are one student with special needs in the class (Rock, Gregg, Ellis, & Gable, 2008). This is similar to Australia, where two-thirds of all students with special needs receive education in general education schools (Forlin, Chambers, Loreman, Deppeler, & Sharma, 2013). However, the proportion of students with special needs who are educated in general schools in developing countries is relatively lower than that in advanced countries.

Successful inclusion requires a learning environment that includes a diverse group of individuals and key elements. These elements includes school reform, changing attitudes, cooperation, teaching strategies and enhanced classrooms (Swart & Pettipher, 2011). Individuals who play a vital role in the effective implementation of inclusive education include parents, teachers, school administrators, specialists in various fields and support teams. The results of the studies confirm the view that among all these individuals, teachers are key to successful inclusion and that inclusive education can only be successful if teachers are part of the team that leads this process (Malone et al., 2001). Therefore, teacher participation is an essential and integral component of an effective implementation of inclusive education (Haskell, 2000; Forlin, Cedillo, Romero-Contreras et al., 2010; Donald et al., 2010).

Educational literature indicates that teachers are facing increasing stress to meet the unique needs of learners in inclusive classes (Berry, 2010). This requires them to hone their knowledge and skills, develop new knowledge and skills to fulfill their roles as open minded teachers in order to accommodate the curricula, corporate with other partners like special education teachers ((Swart& Pettipher,2005).

Thus, in order to enable inclusive education, teachers need to adapt to their changing roles. This requires a great sense of self-efficacy (Savolainen, Engelbrecht, Nel & Malinen, 2012). Self-efficacy of teachers is one of the factors that has received a great attention among researchers (Al-Qumeiz,2019; Savolainen, et al., 2012; Meijer & Foster, 1988; Soodak & Podell, 1993). Several studies have indicated that self-efficacy is an indicator of a willingness to teach in inclusive classes (Forlin et al. 2010; Malinen, Savolainen, & Xu, 2012; Savolainen et al. 2012). Research shows that teachers with higher levels of self-efficacy have more positive attitudes toward inclusion (Malinen, et al.,2012), are less likely to refer a disadvantaged student to special education services (Soodak & Podell, 1993), and more willing to provide Special assistance to students with lower achievement levels (Ross, 1992). Self-efficacy influences teaching behaviors and the use of creative teaching in the classroom (Holzberger, Philipp, & Kunter, 2013; Schiefele & Schaffner, 2015; Zee & Koomen, 2016). Educating students with special needs in the inclusive classes impose teachers in front of educational challenges (Jennett, Harris, & Mesibov, 2003; Scheuermann, Webber, Boutot, & Goodwin, 2003). The main disabilities associated with students with special needs affect the increased exposure of teachers to stress and burnout, which are factors associated with the attrition of teachers' energies (Billingsley, Carlson, & Klein, 2004; Boyer & Gillespie, 2000). Teachers with high self-efficacy have low stress, they continue to teach longer, and are more motivated than teachers with low self-efficacy (Schwarzer & Hallum, 2008; Ware & Kitsantas, 2007). Therefore, the self-efficacy of teachers is a protective factor for psychological burnout common in the teaching profession. Researchers emphasized that it is necessary to pay attention to the sources of self-efficacy in order to explore how individuals build the beliefs of their own efficacy (Lent, Lopez, & Bieschke, 1991). Because teachers ’self-efficacy in the inclusive classes is associated with many positive outcomes within the class, the researchers have tended to explore the sources of teachers’ self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is based on four sources: performance achievements, alternative or indirect experiences, verbal persuasion and emotional states (Bandura, 1997). Performance achievements are defined as feeling satisfied with successful teaching experiences in the past. Verbal persuasion refers to self-efficacy judgments based on verbal stimulation of others such as colleagues, supervisors, managers, students, and parents. Emotional states represent control of the level of activation (i.e. fatigue, stress, anxiety, tension and mood), which in turn can directly affect the provisions related to teaching ability (Fernandez-Rio et al., 2016). Uncovering the sources of self-efficacy for teachers in the inclusion classes provides an important basis for obtaining important insights on how to enhance self-efficacy during teacher training (Gaskill & Woolfolk-Hoy, 2002; Lebone, 2004; Henson, 2002). Understanding the potential sources of teacher self-efficacy in the inclusive classes helps to identify factors that should be targeted in professional development activities for teachers (Morris, Usher, & Chen, 2017).

Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk-Hoy (2007) notes that teacher self-efficacy is context specific. It is important to test the theoretical assumptions underlying self-efficacy in a variety of cultural contexts. The cultural context is one of the most important contexts that may lead to the variation of teachers ’self-efficacy. Many literature emphasizes the need for multicultural studies of self-efficacy, which often depend on culture and historical background (Klassen & Chiu, 2010; Klassen, 2004b; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). It is possible that the sources of self-efficacy of inclusive practices will depend on cultural background.

Problem Statement

Research over the past three decades on implementing inclusive education indicates that the success or failure of inclusion depends on many factors such as state policies, the availability of resources, the leadership of the principal, employees cooperation, and the characteristics of teachers such as the acquisition of knowledge, skills, , attitudes toward inclusion and self-efficacy (Kuyini, Desaib & Sharma, 2018; Loreman, Sharma & Forlin 2013; Leyser, Zeiger & Romi, 2011; Kuyini & Desai, 2008; Friend & Bursuck, 2009). The self-efficacy of teachers in the inclusive classes is one of the most important factors that may lead to the success or failure of the inclusion. It is associated with many variables such as attitude towards inclusion, copying strategies and motivation (Savolainen et al. 2012; Klassen et al. 2011). It affects teachers making essential adjustments in the classroom, such as adjusting curriculum content or instruction (De Boer, Pijl, & Minnaert 2011; Wilson et al. 2016).

Bandura (1997) notes that teachers build their beliefs about self-efficacy by processing information from four sources: performance achievements, alternative or indirect experiences, verbal persuasion, and emotional states. Research recently tended to reveal the sources of this self-efficacy , Which may contribute to enhancing the self-efficacy of in-service teachers and identifying factors that should be targeted in professional development programs and activities. Many literature emphasizes the need to conduct multicultural studies of self-efficacy. These international comparisons are useful because it provides insight into the factors that constitute self-efficacy beliefs in different cultural contexts. Besides that, there are not enough empirical results so far to demonstrate whether countries with a long history of implementing inclusion in general education schools differ from the countries in which inclusion has begun to be implemented. Comparing the self-efficacy of teaching practices in inclusive classes and their potential sources between Saudi Arabia and Egypt may benefit in providing new insights into the factors that constitute this efficacy. The results of comparative studies may have implications for how to prepare and support pre-service and in-service teachers to implement inclusion in general education schools (Sharma, Aiello, Pace, Round & Subban, 2018).

The current research problem arises in the following questions:

- Are there statistically significant differences between mean scores of self-efficacy for Saudi teachers and Egyptian teachers?

- What is the ability of performance achievements, alternative experiences, verbal persuasion and emotional states in predicting the self-efficacy of Saudi teachers in inclusive schools?

- What is the ability of performance achievements, alternative experiences, verbal persuasion and emotional state in predicting the self-efficacy of Egyptian teachers in inclusive schools?

Methodology

Participants

Participants in the study are in-service teachers working in elementary schools in Saudi Arabia and Egypt in inclusive schools for students with special needs and regular. They were chosen intentionally.

The Saudi sample were (250) male and female teachers representing (8) schools in Arar city, affiliated to the Education Department in the Northern Borders Region, north of Saudi Arabia. The study instruments were distributed among them, during the month of April 2019, (96) were retrieved, so, the retention rate was 38.4%.

The Egyptian sample were (200) male and female teachers representing (6) schools in Beba, affiliated to the Beba Educational Administration in Beni Suef Governorate, south of Egypt. The study instruments were distributed among them, during the march of 2019, (88) were retrieved, so, the retention rate was 44%.

Instruments

- Teacher self- efficacy scale: This scale was developed by Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk -Hoy (2001) with the goal of determining the strength and nature of teachers' self-efficacy beliefs. It consists of three dimensions including instructional strategies, student engagement, and classroom management. The researcher used the abbreviated form (12 items). The items were distributed among the three dimensions shown as follows: instructional strategies (5, 9, 10, 12), student engagement (2, 3, 4, 11), and classroom management (1, 6, 7, 8). For each item asked teachers to assess their ability to influence the outcome ("How much can you do?") in a 9-point Likert scale from 1 to 9: Nothing (1-2), very little (3-4), Some infulence (5-6), quite a bit (7-8), a great deal (9). Consequently, the maximum score for the scale was 108, and the lowest score, 12. The scale author used factor analysis to test the validity of the construction by 225 in-service and 111 pre-service teachers. Factor analysis showed three factors, which accounted for 65% and 61% of the variance respectively. The factor analysis of the current study showed three factors that accounted for 78% of the variance. The reliability of instructional strategies, student engagement, and classroom management dimensions were 0.93, 0.94, and 0.95, respectively. The general reliability of scale was 0.96.

- The sources of self-efficacy scale: The SSE scale was prepared by Hoi, Zhou,Teo & Nie (2017). The scale consists of 26 items divided into four dimensions, including performance achievements (1-6), alternative experiences (7-12), verbal persuasion (13-20), and emotional states (21-26). The responses are according to a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7 ). The scale authors used factor analysis to investigate the validity of the construction. Factor analysis showed four factors, which accounted for 71% of the variance. The authors of the scale used also confirmatory factor analysis. The results indicated that the scale had acceptable indicators (χ2 (293) = 636.40, SRMR = .057, RMSEA = .069 (.061, .076], TLI = .90, CFI = .91). Confirmatory factor analysis was used in the current study to test the indictors of the SSE scale. The results showed acceptable indicators (χ2 / df = 133.154; GFI: .900; CFI:.911; RMSEA: .058; SRMR: .051). The authors of the scale indicated that the alpha coefficient of the four dimensions of the scale; performance achievements, alternative experiences, verbal persuasion, emotional states were 0.89, 0.86, 0.90, and 0.87. The general reliability of scale was 0.81. Regarding the current study, the researcher used the Alpha-Cronbach coefficient. The results showed a significant values for the four dimensions: performance achievements, alternative experiences, verbal persuasion, emotional states as following; 0.93, 0.93, 0.93, and 0.94.

Procedures

After obtaining official approvals from the Deanship of Scientific Research at the University of Northern Borders, the researcher distributed the study measures to the research sample in Saudi Arabia and Egypt. After two months, the researcher analyzed the data using SPSS (Ver.23).

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 23 software. The researcher used independent- samples t-test to answer the first question of the study. The researcher used stepwise multiple regression analysis to answer the second and third question for the study.

Results and discussion

Regarding the first question “Are there statistically significant difference between mean scores of self-efficacy between Saudi teachers and Egyptian teachers?

independent –samples t-test was used to analyze the data. Results indicated that there were a significant differences in all dimensions of self-efficacy and overall self-efficacy in favor to Egyptian teachers. Table 1 presents the results.

Table 1.

Results of the "t" test for the differences in self-efficacy and its dimensions between Saudi and Egyptian teachers.

test for the differences in self-efficacy and its dimensions between Saudi and Egyptian teachers..PNG)

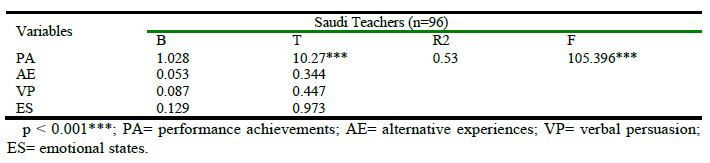

Regarding the second question “What is the ability of performance achievements, alternative experiences, verbal persuasion and emotional states in predicting the self-efficacy of Saudi teachers in inclusive schools?

Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to analyze the data. The model was able to predict (53%) of self-efficacy.. By the stepwise method, four predictors were included in the model; performance achievements, alternative experiences, verbal persuasion, and emotional states, one of these; performance achievements successfully predicted self-efficacy among Saudi teachers. Table 2 presents the results.

Table 2.

Results of stepwise regression analysis of self-efficacy predictors among Saudi teachers.

Regarding the third question “What is the ability of performance achievements, alternative experiences, verbal persuasion and emotional states in predicting the self-efficacy of Egyptian teachers in inclusive schools? Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to analyze the data.. The model was able to predict (13%) of self-efficacy. By the tepwise method, four predictors were included in the model; performance achievements, alternative experiences, verbal persuasion, and emotional states. One of these; performance achievements successfully predicted self-efficacy among Egyptian teachers. able 3 presents the results. Table 3 presents the results.

Table 3.

Results of stepwise regression analysis of self-efficacy predictors among Egyptian teachers.

.PNG)

The results of the research indicated in its answer to the first question that there were statistically significant differences between Saudi teachers and Egyptian teachers in the self-efficacy of inclusive practices and its dimensions; teaching strategies, student engagement and class management in favor to Egyptian teachers, although the general level of self-efficacy in both countries was below average based on the study scale (12-108). This result is consistent with Savolainen et al. (2012), which indicated that there are significant differences in a certain dimensions of the self-efficacy of teachers in inclusive schools between Finland and South Africa, Sharma and Jacobs (2016) that indicated there are significant differences between general education teachers in India and Australia in self-efficacy within the inclusive classes, Sharma, et al. ( 2018) which indicated that there are significant differences in self-efficacy in the inclusive practices between teachers in Italy and Australia, and Miesera and Gebhardt (2018) that indicated significant differences in self-efficacy in inclusive practices among teachers in Canada and Germany. The researcher attributes this in light of the associations between self-efficacy and job satisfaction, classroom teaching practices and student learning outcomes (Anderson, et al., 1988). In the context of Egyptian education, competition among students inside schools is very high, and the teaching strategies used by teachers are more efficient and effective. This is due to the fact that the majority of Egyptian teachers work in private teaching after the end of school hours. The way to increase the financial returns from this courses is to improve the teaching process in a desire for students to reach high levels of achievement excellence. This is consistent with Heine and Hamamura (2007) and Kurman (2003) indicated that the self-efficacy of teachers increases in countries where independence is greatly emphasized. Independence means reducing educational supervision, which applies to teachers in the field of private teaching.

Besides, the concept of inclusion is a relatively recent concept among Egyptian education schools. Stakeholders for educational policies in Egypt have approved a rewarding financial incentives for teachers in inclusive schools and providing them with a qualified and recent training courses. Besides that, assigning special education teachers as experts and supportive for general education teachers in each educational administration in which the inclusion is applied are provided. These external factors can lead to a shift in the teachers ’locus of control from being external to an internal where teachers believe that the outcomes are more based on a person’s own behavior than on external sources and circumstances (Rotter, 1966). This is consistent with what Teschanen-Moran and Woolfolk-Hoy (2001) emphasized, the close association between locus of control and self-efficacy. These cultural differences in self-efficacy can be attributed to the self-enhancement needs (SEN). SEN is defined as a motivation to search for activities and social trends leading to maintaining a positive image. The motivation of Egyptian teachers to teach students with special needs in inclusive classes stems from their desire to preserve a positive image compared to the Saudi teachers. The researcher believes that the efforts of in-service teacher training in Egypt in recent years, which focused on developing the skills of teachers in the classroom, with special reference to skills in behavior management in the classroom with various groups of students, have led to an increase in teachers' belief in their ability to performing various teaching tasks with acceptance quality in different teaching situations and thus improving their level of self-efficacy. Therefore, the results seem to indicate that Egyptian teachers now generally have a stronger belief in their ability to manage diverse needs and behaviors in the classroom, design and implement educational activities to assist different learners in learning, and competence in ensuring student participation and motivation towards learning.

The results of the research indicated in its answer to the second and third questions Performance. achievements or mastery experiences were the most predictable sources of self-efficacy for teachers in self-efficacy in inclusion practices, whether in Saudi Arabia or Egypt. These results are consistent with what Bandura (1997) indicated that performance achievements are the most powerful source of self-efficacy. It is consistent with (Milner, 2002; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk-Hoy, 2007; Bruce & Ross, 2008; Usher & Pajares, 2008; Malinen et al., 2012; Yada, et al., 2019; Wilson, Woolfson & Durkin, 2020). These results are inconsistent with Sharma, Shaukat, and Furlonger (2014) that indicated developmental knowledge of legislation and policies, and less concerns about teaching in inclusion classes, were key predictors of improving the teaching efficiency of inclusive practices. it is inconsistent with Emam and Al-Mahdy (2019) which indicated the variation of the self-efficacy of general education teachers in inclusion schools in Oman, with gender differences and the number of years of teaching experience.

The researcher attributes the current results in the light of social cognitive theory. SCT indicates that the reciprocal relationship between behavioral and personal factors, where teachers make decisions related to their perceived capabilities based on their previous performance. When teachers look at their past performance, they can determine the extent of their ability to teach in the inclusive classes. When they believe that a certain strategies were successful, they can use this experience to enrich their practice in the coming years. Likewise, through experience, teachers may become confident about their effective working strategies which leading to enhancing the effectiveness of classroom management. Previous experience also helps teachers motivate and engage students, which enhances the effectiveness of student engagement in the classroom.

Conclusions

The results of the current study showed a significant differences of self-efficacy in inclusive schools between Saudi teachers and Egyptian teachers in favor to Egyptian teachers. Results indicated that only performance achievements or mastery experiences are the successful predictor of self-efficacy among Saudi teachers and Egyptian teachers. The results of the study indicate that the performance achievements explained 53% of the variance in the self-efficacy of Saudi teachers, while 13% of the variation in the self-efficacy of Egyptian teachers.

The results of the study indicate that the performance achievements explained 53% of the variance in the self-efficacy of Saudi teachers, while 13% of the variation in the self-efficacy of Egyptian teachers. The researcher attributes this to that there may be other sources related to the self-efficacy of Egyptian teachers such as mastery of knowledge (Morris et al., 2017), collective efficacy (Goddard & Goddard, 2001), school environment (Wilson, Woolfson & Durkin, 2020), training, and direction towards inclusion.

Recommendations

According to the results, the researcher presents the following recommendations: First, Given the small sample size , the results cannot be generalized. Therefore this study must be repeated again by a large sample. Second, In light of the lower of the percentage of explained variance by the performance achievements for the self-efficacy of Egyptian teachers, future research must address others sources of self-efficacy of teachers in inclusive schools in Egypt. Third, Questionnaire -based studies cannot provide complete answers to explain the difference in cultural differences in self-efficacy among teachers. This is requires in-depth qualitative analysis, therefore future research should rely on a mixed method that combines quantitative and qualitative analysis in order to achieve this goal. Fourth, It is important for researchers in Saudi Arabia and Egypt to conduct comparative studies with samples from different societies. This will help stakeholders to assess the Saudi and Egyptian situation related to teacher efficacy in an international context. This can help in measuring improvements compared to these other societies.