Phonosemantic interpretation of lexical units in the context of Russian and Slovak linguocultures

ABSTRACT

Phonosemantics is one of the youngest disciplines in the modern linguistics but takes an important part in the intercultural communication. The purpose of the article is to carry out the comparative analysis of lexical units of the Russian and Slovak language systems from the perspective of phonosemantics and philological hermeneutics. There has been made an attempt to study the correlation between the phonetic and semantic motivations of lexemes and paroemias (proverbs and sayings) in the system of the Russian and Slovak languages on the basis of the phonosemantic analysis and hermeneutic method. The mechanism for determining the language connotation on the knowledge based system makes it possible to reveal the linguocultural peculiarities of phraseological units, taking into account national-cultural, territorial, ethnolinguistic factors provided the individual’s cognitive abilities are activated. The problem of decoding of semantics in the situation of cross-cultural cooperation is not researched only from the view of the traditional linguistics, but also by means of cognitive activities: perception, presentation, reflection, interpretation. The adequate interpretation of the linguo-cultural phenomena and lexical units is the reflection in the internal communication aimed at the decoding of cultural and language code. In the external communication the reflection of the individual is expressed in the interpretation. The phonosemantic analysis, based on the description of natural-cultural lexical blocks from the view of philological hermeneutics, was revealed at first differences and similarities in Russian and Slovak languages; secondly, it were determined the so-called linguocultural codes. The analysis of lexical units in the Russian and Slovak languages has revealed common and distinctive peculiarities of the languages regarding their phonology and semantics. Perception and interpretation of linguistic units in foreign culture helps to achieve the most important communicative and pragmatic purpose – the establishment of intercultural and interpersonal parity and mutual understanding in the process of communicative interaction.

keyword

linguocultural code, semantic interpretation, connotation, linguistic consciousness, phonetic motivation, mental field, subject of reflection

Introduction

The problem of combining meaning and sound imagery of lexical and especially phraseological units in foreign culture is of research interest in the modern science. The point is that all sounds are associated with a certain meaning. As is known, in the speech practice the phonosemantics aspect are actualized two components: sound and phonostylistics.

For successful intercultural communication speech partners should have equal communicative competence, in this case the linguistic, the cultural competence, the cognitive ability to understand and give the interpretation of the meaning. The difficulty lies in the fact that the motivation of phonetic meaning may be different even in the languages of the same language system. Therebly, the article is aimed at studying the mechanism of perception and interpretation of the meaning of lexical units having a similar sound shell in Slovak and in Russian, sayings through the reflection of an individual.

In an anthropocentric scientific paradigm that phonosemantic difficulties in the process of intercultural communication are most informatively considered from the perspective of hermeneutics is the interpretation of meaning.

It seems that the problem of interpretation and perception of intercultural situations is much deeper and goes beyond phonology. It is phonology that, due to its ambiguity, deepens the process of perception and displays it in the perspective of hermeneutics, into the so-called reflexive-discursive dimension – the communicative space of the reflexive “I” within which the comprehension and interpretation of the perceived, as well as the regulation of speech activity, take place.

Having determined the types of knowledge that contribute to adaptation to foreign linguoculture, the disclosure of linguocultural code, we turn again to the language personality. In other words, achieving the successful interaction, the speaker or listener will intensify its pragmatic potential, applying strategies and tactics of the appropriate level.

Theoretical framework

The problems of the interaction of language and culture in modern linguistics are resolved in various research directions: linguocultural– the study of linguistic phenomena through national-cultural specifics (V.A.Maslova (2007), V.V.Krasnykh (2002), M.A. Kulinich (2017), etc.); psycholinguistic – the study of the processes of perception and understanding of linguistic and cultural phenomena; anthropological – human interaction and pragmatic – the study of the peculiarities of interpersonal interaction in intercultural communication; hermeneutic –correlation and interaction of the language, consciousness, and culture (G.I. Bogin (1990) etc.

As a result of globalization and increasing intercultural cooperation, the intercultural approach is considered to be an inherent part for teaching both a foreign language and related disciplines, which sets the interdisciplinary character of the given study (Lišková, Štefančik, 2016, p. 9).

Regarding to the education in Russia the most scientists come to the conclusion that the present realities suggest the need for each person involving in to the culture change. This difficult problem can be solved only with the help of culture and education deep integration Aryabkina, Donina, 2020, p.213). This thesis emphasizes the importance of culture in language learning.

The language is closely connected with the culture, and in this connection the subject of speech, or the speaker, occupies an intermediate position, being the carrier of both the language and culture. S.G. Ter-Minasova’s statement that “a language reflects both the human world and culture, as well as keeps the culture and passes it from generation to generation has become an axiom now and determines the development trends of the modern theory of intercultural communication” (Ter-Minasova, 2008, p. 100).

S. G. Ter-Minasova’s opinion on the priority of the reflecting function of the language is shared by A. P. Sadokhin in his study of the correlation between the language and culture. According to the scientist, “any language is a specific means of storing and transmitting information; it is a means of controlling human behavior as well. Due to the language, human experience, cultural norms and traditions are passed one to another generation, thus the continuity of different generations and historical epochs is supported through the language” (Sadokhin, 2009, p.63).

The abovementioned goes along with V. Humboldt’s theory about the so-called “spirit of the nation”, which finds its reflection in the language of each nation (Humboldt, 2001, p.35).

In the “Logical-philosophical” treatise, L. Wittgenstein made an attempt to solve basic philosophical problems regarding the relation between the language and the world. In particular, L.Wittgenstein believed that a language reflects the world, because the logical structure of the language is identical to the ontological structure of the world (Wittgenstein, 2005, p.58).

In our opinion, another scientist, J.L. Weisgerber was the very scientist to exactly determine the status of language in the value system; he extended V. Humboldt’s theory by actualizing the importance of linguistic personality as the bearer of language and culture. According to J.L. Weisgerber, the language is an intermediate world (Zwischenwelt) between man and the outside reality (Weisgeber, 2004, p.123).

Thus, when one considers the relation between the language and culture, the key figure is the linguistic personality as the bearer of national-cultural and linguocultural peculiarities. With the help of the language, people’s thoughts, their mental attitude to the various phenomena around, are verbalized. The language is a representation of the conceptual image of the world, where the culture serves as the background.

In the act of decoding the meaning of the utterance, the cognitive process, the mechanism of perception and understanding, is the most important one. In our study we share the V.A. Maslova and V.M. Pimenova’s views who define the functional peculiarities of the code as a generative-interpretative aspect of the sign system, therefore, much attention is paid to the process of perception and understanding (interpretation) of the meaning conveyed by the code (Maslova, 2016, p.26). Within this approach, the cognitive function of linguistic consciousness is emphasized, since the language and culture in the anthropological aspect are tied closely and primarily with the thinking process. First of all, it is important to take into account the irrelevance of the conceptual thesaurus of different ethnic group representatives. According to S. Ter-Minasova, the path from the real world to the concept and further to the verbal expression is different for different peoples due to the differences of their history, geography, life peculiarities and, correspondingly, the differences of their social consciousness development (Ter-Minasova, 2008, p. 47).

A similar point of view is shared in the intercultural communication studies by M.A. Kulinich and O.A. Kostrova. The researchers believe that mental (concepts, stereotypes, artifacts) and semantic units (words, phraseological units, proverbs, syntactic structures) do not coincide in their volume in different linguocultures, therefore, this indicates the difference of linguistic consciousness of different ethnoses (Kulinich, Kostrova, 2017, p.42).

The above mentioned proves the fact that the language of any ethnos reflects its culture and originality, which has been developed for centuries and further fixed in historical memory. It is quite obvious that the knowledge of another language without any cultural basis does not always help understand the speaker. On the other hand, the sound shell of the words can be reason of unsuccessful communicative interaction.

Methodology

Adhering to the hypothesis of E. Sepir and B. Worff, which states that the linguistic personality occupies the dominant position as the bearer of linguistic and national-cultural information, and realizes its communicative potential due to cognitive abilities of the highest level: thinking, perception, understanding, this study considers the mechanism of immersion in intercultural interaction from the viewpoint of a cognitive-pragmatic approach.

The focus of this study, which is based on our own observations and the process of Slovak and Russian linguoculture acquisition, lies in the complexity of the interpretation of lexical units naming everyday activities, as well as the paroemias accompanying everyday discourse. During the research, 150 lexical units of Russian and Slovak languages and 100 proverbs and sayings were analyzed by the students of the University of Economics in Bratislava and of the Ulyanovsk State Pedagogical University. At first the respondents should identify similar words in their native language in a speech context. At the next stage it was proposed to translate speech combinations. At the final stage, the respondents had to explain what factors determined the choice of translation and the further interpretation: sound similarity or meaning appropriate to the context, using the hermeneutical method.

In a number of situations of intercultural interaction, on the one hand, due to the one-system nature of the considered languages, there has been marked the similarity or coincidence of many linguistic units, which undoubtedly facilitated the process of understanding. For example, myš– mysh’ (a mouse), kameň – kamen’ (a stone), les – les (a forest). On the other hand, there were also words and speech expressions that did not coincide in meaning, thus making it difficult for understanding: slov. čerstvý – rus. svezhij (fresh).

This observation is confirmed by other authors. When structuring language equivalents, P. Kvetko focuses his attention on the translation of idioms in the compared languages and on the basis of system analysis points out absolute, functional equivalents. Also he identifies a group of so-called deceptive equivalents, which due to sound similarity create the illusion of the same meaning of the word (Kvetko, 2015, p. 153).

In this case, it is appropriate to single out a phonological aspect in the comparison of Russian and Slovak phraseological units within the study of single-system languages, which presupposes similarities and differences in the phonological system of both languages and directly influences the process of interpreting the meaning of one or another lexeme in the complex of paroemias. The complexity and ambiguity of the mechanism of the interference of the sound and written language code from the perspective of phonology is indicated by N.K. Ivanova, who actualizes the sociolinguistic factor of the sound structure of the language (Ivanova, 2012, p. 222).

As it has already been mentioned, the very first understanding difficulty arises at the initial stage – with phonetic perception of the word. The ambiguous nature of the phonetic similarity of the compared languages was pointed out by A.P. Zhuravlyov in his studies on phonosemantics. In particular, the scientist emphasized that phonetic motivation is inherently more complicated than semantic motivation (Zhuravlev, 1991, p. 39).

This statement is proved by the following examples: Slovak svetlo – Russian svet (light), Russian mir (world) – Slovak mier, svet.

The Slovak lexical unit “pozor” (Russian vnimanie (attention)) acquires inadequate semantic interpretation in Russian, as well as the Slovak vulgarism “pitomec” (Russian durak (fool)), which does not meet a true semantic interpretation in the Russian linguistic world image.

So, the Slovak female name Jarmila can cause a sound association with the word Mila, which is a derivative from the Russian female name Lyudmila, which presupposes the stress on the second syllable, according to the Russian linguistic world image. However, according to Slovak phonology, the first syllable is stressed, and this is explained by the etymology of the female name “Jarmila”. In the old Slavic as well as in the modern Slovak language “Jar” means “spring”, which is the core of the connotation.

On the other hand, the diminutive form “Jarka” from the Slovak name Jarmila in the lexical paradigm of the Russian language has a completely different connotation. In the big explanatory dictionary of the Russian language, edited by D. N. Ushakov, “yarka” means a young, ewe lamb. In the Slovak language it has no meaning at all.

However, despite the phonetic similarity of the two languages of the Slavic group: Russian and Slovak, there are discrepancies that may lead to an inadequate interpretation of the meaning. In some cases, due to phonetic similarity, the semantic motivation is the same. The phenomenon of homonymy, when the form coincides completely, and while the meaning – only partially – actualizes the study of semantics, and, thus, represents the field of study of linguistic units with a comparative method.

Results and discussion

The formulation of the researched problem allows us to consider this problem from a different perspective, going beyond the real communicative situation, in the mode of internal communication through the interaction between the real I (subject of speech) and the sub-I (I in a reflexive position). It is the reflection of the subject of speech that reveals the semantics of comprehension and interpretation. The hermeneutical method reveals the subtlest nuances of intercultural interaction. As one knows, the speech should be comprehended, motivated, and therefore, the next stage after the perception of the sound code of the word, is understanding and decoding of the meaning.

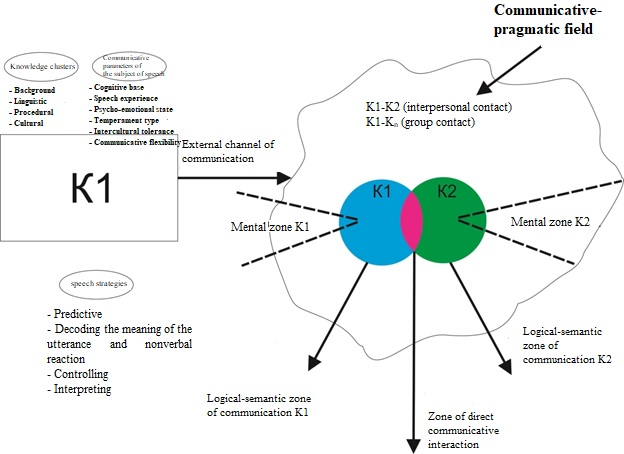

Scheme 1. Levels of interaction of the sub-I (Reflective I) and the realI (subject of speech) in two modes of communication: external and internal.

Considering the peculiarity that the communicative program of speech partners is built in two modes of communication: external – within the communicative-pragmatic space and in the internal one – within the so-called reflexive-discursive dimension, it is appropriate to talk about the binary nature of intercultural interaction.

Moreover, the external plan of communicative interaction is managed from within on the basis of the activated knowledge clusters: linguistic, cultural, background, which are updated due to procedural knowledge. The implementation of these types of strategies: predictive, decoding, controlling (regulating), interpreting determines the pragmatic semantics of communicative behavior. The logical-semantic zone of each speech partners reflects a linguistic and cultural basis and intentionality. The range expansion of the spectrum of direct communicative interaction in the external mode of communication means reducing the level of linguistic and cultural barriers, as well as taking into account the national and cultural specifics within the communicative-pragmatic aspect of representatives of different linguocultures.

Scheme 2. Interpersonal interaction of speech partners in the situation of intercultural communication in two modes of communication: external and internal.

The abovementioned statements let us assume that the trajectory of the mechanism of the speech-activity of the individual as a representative of a particular language and culture unfolds in the following sequence: culture-consciousness-language (Morozkina, 2015, p. 184).

Types of linguolcultural codes territorial: ekhat v tulu so svoim samovarom, yazyk do kieva dovedyot (to go to Tula with your own samovar, the tongue can get you to Kiev);

dimensional: Slovak “čo by kameňom dohodil”(one can reach by a stone) – Russian “rukoi podat’ (one can reach by a hand)”

temporal: Slovak “ráno je múdrejšie večera”– utro vechera mudreje (the morning is wiser than the evening);

household: Slovak “dať hlavu do chomútu” / “strčiť hlavu do chomútu” (to lose one’s freedom) – Russian “zhenit’sa”(to get married), “nade’t khomut na sheyu” (to put on a horse-collar on one’s neck)

perceptive: Slovak “opitý do nemoty” (drunk to unconsciousness) – Russian “napit’sa do bespamyatstva”(to get drunk to unconsciousness);

natural: Slovak “klame až sa práši” (lies so that even the dust flies);

food: Slovak “dostať sa do peknej kaše” (getting into the “beautiful”- “good” porridge) – Russian “popast’ v nelovkuyu situatsiyu” (to get into an awkward situation); Slovak “mať maslo na hlave” (to have butter on the head) – Russian “byt’ nechestnym” (be dishonest (a sign of guilt, an unclean conscience);

zoological: Slovak “byť chudobný ako kostolná myš” (to be poor as a mouse living in a church) – Russian “byt’ ochen’ bednym” (to be very poor); Slovak “bolo koze dobre, išla na ľad tancovať” (the goat lived well, but it went to the ice to dance) – Russian “naiti priklucheniya na svoyu golovu” (to find adventures for one’s head); Slovak “ani psa nehodno von vyhnať” (even a dog cannot be kicked out to the yard) – Russian ”pogoda takaya, chto sobaku na ulitsu ne vygonish” (the weather is such bad that you cannot kick a dog out onto the street);

material: Slovak “žiť si ako v bavlnke” (one lives as if in cotton) – Russian “zhivet v zolote” (one lives in gold) / “žiť si ako prasa v žite” (one lives like a pig in wheat).

Differences at the morphological level (proper names).

In such a waymore than 150 lexical units were investigated with the help of phonosemantic analysis method. It was found that the correspondence between the languages at the phonetic and lexical-semantic level is 30%.

The results of the observation show that the interpretation of the national specificity of the meaning of speech units in the compared linguistic systems is determined not only by linguocultural peculiarities, but also by individual-personal ones, since the language is the product of the individual’s cognitive and speech activity, where one should take into account personal, individual and national-cultural characteristics.

Since K. Azhezh claims that the linguistic sign belongs to the sphere of conceptual thinking, then this cognitive ability of the higher level is peculiar only to a person capable of recognizing the objects of the external world and adapting his behavior to them (Azhezh, 2003, p.97).

Let us turn to the G.I. Bogin’s opinion regarding the interpretation of the nature of the sign by the individual. According to G.I. Bogin, the experience of the individual is both national, social, relating to himself only (Bogin, 1990, p.26). It seems that this thesis actualizes the following aspects in the study of the sign: intercultural, social (connection with the real world), individual-personal, and, thus, places the focus of research on the correlation of sound and sign.

Each sound is symbolic in its nature, and it is important that the sound is synthesized in the conditions of reality and based on the resource of the background knowledge of the listener, and then reflected in the consciousness; on the basis of this representation an image is formed in the conceptual system of the individual. The decoding process of the semantic content of a lexical unit can be represented in the form of an algorithm: sound → value → image → symbol. It is important to note that in the inner speech itself, during the process of intentional experience perception, a transition from the phase of reflection of the meaning to the formation of the symbol takes place.

In intercultural interaction, the interpretation of meaning and the definition of a symbol can become a difficulty because of an incorrect perception of the sound form of a word, the so-called phonological deception. Although the language is similar to symbols, because it is basic and contains many cultural forms, it conveys meanings in a more complex and complicated way (Šajgalíková - Rusiňáková, 2016, p. 34).

In our opinion, the most relevant examples are those where, in the very first stage of the chain, sound → meaning, due to ambiguous phonetic motivation, the inadequate image of words is generated: Slovak: chalupa – a house in the village, i.e. a village house, Russian: khalupa (a hut), khibara, lachuga; unlike the Slovak word, in Russian the word is used with a pejorative connotation. It is possible to give other equivalents, e.g. rodina (Slovak) – semja (family) (Russian). Thus, the sound form of the word rodina forms false associations with the Russian rodina (motherland); Russian: krasnyi (red) –Slovak: červený, Slovak krásny – Russian: krasivyi (beautiful), Russian: cherstvyi (stale) – Slovak. zatvrdlý, suchý, starý (i.e. not fresh), Slovak čerstvý – Russian: svezhii (fresh), Russian: vonyat’ (to stink) – Slovak: smrdieť, páchnuť, zapáchať (i.e. to smell unpleasantly) and vice versa: Slovak: voňať – Russian: paknut’, blagoukhat’ (to smell pleasantly).

According to O. A. Leontovich, for intercultural communication, it is necessary to form a special monitoring mechanism that would, along with the language component of the code, oversee its cultural component. It is unrealistic to know the whole foreign culture, but it is possible to form an openness to its perception, so it is a question of developing the ability to perceive the signals of the inclusion of a cultural code and the readiness of its decoding, which could minimize, if not eliminate, moments of intercultural misunderstanding (Leontovich, 2007, p. 39).

Thus, the cognitive procedure of perception and interpretation of the meaning of speech units is reflexive in its essence, since the processes of perception, reflection of sound, interpretation of meaning through interpretation and, at the final stage, verbalization of the decoded image in external speech, presuppose activation of consciousness, comprehension.

G.I. Bogin’s idea about the three-level experience of the individual in the situation of interpersonal communication, let us consider the mechanism of understanding as a component of the reflective activity of the individual in the intercultural context. The process of perception and understanding of the utterance in the situation of intercultural interaction flows with the help of activation of the universal-objective code. According to N. I. Zhinkin, one of the important components in the system of relations “person vs. text” is the person’s orientation on the background knowledge, the general vision of the situation. Accordingly, one should not understand the speech itself, but the reality (Zhinkin, 1982, p. 92).

A similar idea of the universally-objective code by N. I. Zhinkin, is supported and extended by A. Wierzbicka, who views the issue in terms of the semantics research. In particular, A. Wierzbicka points out the impossibility of understanding a distant culture “in its own terms” without extrapolating it to “our” terms. For a true “human understanding” it is necessary to find the terms that would be both “theirs” and “ours”; one needs to find common terms, or, in other words, universal human concepts (Wierzbicka, 1992, p. 26). For example, the meaning of the Slovak proverb “nosiť drevo do lesa” (to carry firewood to the forest, to work in vain) is quite understood because it is close to the Russian language in its phonetic and spelling structure.

The binary opposition “own-alien” in terms of linguistics can be represented with the corresponding examples: the generally accepted Slovak address to the female “pani” does not correlate with the mental vision of the Russian linguistic consciousness. According to the mental representations of the Russian language personality, the main part of the concept “pani” reflects youth, attractiveness, and is associated with: Pani Valewska, Pani Monica, beautiful Pani, therefore, because of its qualitative characteristics, this concept can be relevant for the use in the Slovak language to a certain limit, and reveals a linguistic-cultural lacuna.

As for the morphology of proper names, there are also differences, thus, there can arise a conflict situation if one does not consider these peculiarities. This mainly concerns the use of diminutive endings in proper names that denote an affectionate variation of words. Vierka, Jarka, Danka, Dianka (for female names), Janko, Peťo or Peťko, Andrejko, (for boys); while in Slovak these names are formed with -ka (for women’s names) or –ko for male names, for example, the Slovak tend to refer to friends or girlfriends as Irka, Verka, Anka, Tamarka, for the Russian people it may look impolite. The Russian variant, for example Dianočka, Veročka, Iročka for the Slovak sounds too “sweet” and is not used.

One should also pay attention to the ending of the Slovak female surnames - ová, with the stress on the ending of the word e.g. Rusiňáková, Lišková, Breveníková. In the Slovak language, the ending –ová is stressed, and this phenomenon is marked as a linguistics interference to Russian female surnames, which does not correspond to the principle of morphology in Russian: for example, instead of Kuzmina, the Slovaks will say Kuzminová.

National-cultural specifics, territorial and mental conditions are most clearly conveyed through proverbs, sayings, phraseological units (idioms). At the same time it may bring much difficulty for the researcher. Thus, the interpretation of the meaning of phraseological units causes misunderstanding in the situation of intercultural communication due to incorrect word for word translation of lexical units and the discrepancy of national cultural peculiarities.

Without reliance on the background knowledge about the country and culture of the language being studied, it is impossible to disclose the connotation of a linguistic expression. For example, common idioms from the Russian language bit’sya kak ryba ob led (hit itself like a fish on the ice),vyiti sukhim iz vody (get out dry of the water) can be misinterpreted due to ignorance of the linguistic and cultural code of the idioms, which make up the paroemic complex. By disclosing the meaning of phraseological units as carriers of cultural information and national mentality, we get access to the linguistic and cultural code of an ethnic community.

V.V. Krasnykh points to the fact that “the culture code should be understood as a “net”, with the help of which the culture covers the outside world, divides it, structurises and evaluates” (Krasnykh, 2002, p. 232).

On the other hand, V. N. Telia, using the semiotics as the base, “equates cultural codes and secondary sign systems; the scientist believes that culture can be understood as the space of cultural codes – secondary sign systems, where different material and formal means are used to convey cultural meanings, or the values are produced by man in the process of the world understanding” (Telia, 1999, p. 12).

Considering the complex process of mastering the language as an ultimate skill, P. Steven suggests using well-designed mental programs which can allow to successfully cope with the processes of perception, argumentation and action (Steven, 2016, p.391).

One can conclude that for the decoding process and adequate interpretation of the meaning of phraseological units, the subject of speech needs a certain mental cluster consisting of types of knowledge. The knowledge of a foreign language is not enough for the process of intercultural communication, there is a necessity to apply background knowledge to successfully perform in a foreign mental field.

As an example one can have a look at the idiom with the territorial component “to go with a samovar to Tula”, understanding of which presupposes the presence of background knowledge of the Russian linguoculture: why to Tula, geographical location and finally, a samovar as a truly Russian attribute. The national and cultural peculiarity is reflected in the Slovak national sayings: "mať peňazí ako maku" (to have as much money as poppies) unlike the Russian proverb: kury deneg ne kluyut (hens do not pick the money, with the meaning a lot of money), “klame až sa hory zelenajú” (a person lies so much that the forests get green). In the first case, the use of the idiom is stipulated by the historical cultivation of poppy seeds on the Slovak soil, and in the second – by the typical Slovak landscape. There is also the phonosemantic deception in the words of the different languages: compare Slovak“hora”– Russian “forest”, the Russian word “gora” (mountain) – Slovak words “vrch”, “kopec”.

The process of correct interpretation of the meaning of idioms can be considerably facilitated with the activation of the previous knowledge, fixed in the subject’s memory and related to intercultural interaction in the present – associative knowledge. The orthographic similarity of lexemes in the following sayings greatly simplifies the understanding of the meaning, see: gora s plech (the mountain fell off the shoulders) is comparable in the meaning with the Slovak “spadol kameň zo srdca” (the stone fell off the heart), rukoi podat’ (reached by the hand) – “čo by kameňom dohodil” (reached by the stone), byť ne v svoei tarelke (to be in the wrong plate) – “nebyť vo svojej koži” (to be in the wrong skin).

The listed types of knowledge can contribute to the mental system, a kind of matrix, with the aim of eliminating linguistic and cultural barriers of understanding.

It can be assumed that in the process of interpreting the meaning of phraseological units of a foreign language, procedural knowledge or knowledge of knowledge management is activated.

In the process of communicative interaction, using the interpretating strategy, the latter is capable to cause various emotions: from a phonetic similarity and recognition of language expression to a false representation of value on the basis of apparent phonological perception. In this case, the individual needs to control his communicative behavior by applying a regulatory function.

Since the communicative process is dynamic in nature and involves the development of communication, taking into account the implementation of the communicative intentions of the speech partners, it is important to use the predictive function, directed at the successful course of intercultural interaction.

Conclusions

As it becomes obvious, in the process of interpersonal communication of representatives of such closely related linguocultures, as Russian and Slovak, many difficulties can arise. When penetrating into a different cultural and linguistic environment, the illusory similarity of the lexical composition of the language, phonetic coincidences can create difficulties for comprehension, therefore, the ability to perceive another culture, differentiation between the characteristics of both cultures, the feeling of the speech partner are impaired; as a result, there can arise a situation of conflict, or, the barrier to intercultural communication. The key to understanding cultural and linguistic code is the ability to consciously use a communication program that would allow both speakers to be in the same linguistic and cultural range in the process of communication.

So, we can conclude that the switching of the cultural-linguistic code in the course of phonological perception and interpretation of lexical units is a complex reflexive process that is inaccessible to direct observation, due to the intentional setting of the addressee and its linguocultural peculiarities.

and the realI (subject of speech) in two modes of communication - external and internal.PNG)

.PNG)