Monitoring of attitudes to the institute of corruption whistle-blowers: a view from Ukraine

ABSTRACT

The research is devoted to the study of the attitude of law enforcement officials, civil servants and ordinary citizens to the institute of corruption whistle-blowers on the example of Ukraine.

To this end, 351 people were interviewed. Generalized results indicate that the vast majority (75%) of Ukrainian citizens are aware of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers.

Ukrainian society has a positive attitude to the corruption whistle-blowers, (51,6%) of those who were interviewed believe that the whistle-blowers fulfil an important mission. The willingness of Ukrainians to participate in exposure of corruption is lower (39,3%) than the number of people who approve activities of the whistle-blowers. It also avouches that not all conditions, including the social and legal protection of whistle-blowers, have been created in Ukraine. There is a high risk of persecution, including from public authorities, according to (89,4%) respondents. The existing system of protection of whistle-blowers is declarative (68%), and there are no positive examples of whistle-blower activity in Ukraine (29,3%).

There are differences in the attitude of different categories of citizens to the whistle-blowers of corruption. The most support (63,3%) whistle-blowers received from representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine, border guards (59,4%), police officers (50%), ordinary citizens (50,6%). Civil servants less approve the institute of corruption whistle-blowers and support (45,9%). The lowest rate (40%) was shown by the representatives of the law enforcement agencies. Average citizens and civil servants (14,7%) showed the highest percentage of distrust in the work of whistle-blowers (15,7%).

keyword

whistle-blower; corruption; counteraction; protection of whistle-blowers; attitude to the whistle-blowers

Introduction

Corruption in Ukraine remains one of the acute problems for Ukrainian citizens. At the same time, the tolerance for corruption is decreasing compared to the previous years (National Anticorruption Survey). Such data are provided by representatives of non-governmental organizations who assist Ukraine to fight corruption. The urgency of corruption counteraction is evidenced by the number of scientific publications, investigative journalism, and etc. Corruption constitutes a real threat to Ukraine’s national security, and its prevention and counteraction must be among the highest priorities of the state. One of the main factors that can influence the fight against corruption is the attitude of the population to this problem.

Corruption is a global problem and is a threat to the most countries in the world. The Ernst & Young Global Fraud Survey of 2015 highlighted the views of 2,825 top-level managers of the highest level from 62 countries. According to this survey, more than a third believes that bribery and corruption are widespread in their countries, and almost half of them can justify unethical behaviour to achieve financial goals (Ernst & Young, 2016). Presented results of the survey are very relevant for Ukraine and we can risk saying that the figures in Ukraine may be higher.

Scientists, experts, politicians, and public figures offer a variety of recipes to overcome this negative phenomenon, among them the prominent place is the implementation of such foreign experience as the use of the corruption whistle-blowers. The institute of corruption whistle-blowers is enshrined at the legislative level with the adoption of updated anti-corruption legislation in 2014 against the backdrop of revolutionary events following the overthrow of President Yanukovych. Since then, legislation governing the use of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers has undergone significant changes toward improvement. However, there have been positive changes in the practice of using the institute of corruption whistle-blowers, and whether the attitude of citizens to this way of fighting corruption has not changed.

The purpose of our research is: 1) to find out whether the citizens of Ukraine are aware of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers; 2) to establish the attitude of the citizens of Ukraine to the institute of corruption whistle-blowers and their willingness to be whistle-blowers; 3) to identify differences in the attitudes to whistle-blowers of different categories of interviewed persons.

The formulated purpose of the study allowed us to identify the main hypotheses that should be tested in the course of its implementation:

1. The vast majority of Ukrainian citizens are aware of the existence of institute of corruption whistle-blowers.

2. Ukrainians are ready to be the whistle-blowers of corruption, and for this purpose all conditions, including social and legal protection, are created in the state.

3. Law enforcement officers have a more negative attitude towards the institute of corruption whistle-blowers than ordinary citizens.

Methodological Framework of the Research

Methodology of the empirical part of our study is based on general scientific methods; the main of which was the method of system analysis. The indicated method, in some way, combines subjective and objective moments of cognition. It is a program for formation and practical implementation of the theory (Berezin, Miroshnikov & Rozhanets, 1976).

Ourof study results are based on the opinion investigation of representatives of law enforcement agencies of Ukraine, civil servants and ordinary citizens. 357 people took part in the survey which was conducted using a special google-form placed in the Internet. The number of people who were interviewed in our opinion is representative.

In addition methods of empirical data processing (analysis, synthesis, comparison and generalization) for comparing and interpreting the data obtained from the results of other investigations were used during the research.

Review of the Literature

This publication is a continuation of scientific research in the field of implementation of foreign experience in combating corruption. In previous work, we have thoroughly analyzed the foreign experience of using the institute of whistle-blowers and also revealed the basis of its implementation in Ukraine (Khalymon, Puzyrov & Prytula, 2019).

In Ukraine, scientific publications on combating corruption are mainly devoted to the problems of organizational and legal support of this process, etc. Kolomoiets, Kolpakov, Kushnir, Makarenkov, & Halitsyna, 2020; Podorozhnii, Obushenko, Harbuziuk, & Platkovska, 2020; Reznik, Shendryk, Zapototska, Popovich, & Pochtovyi, 2019). The publications of foreign scientists have a considerable scientific interest. Among the most relevant is the scientific work of (Kenny, Fotaki & Vandekerckhove, 2018). The mentioned team of contributors conducted a qualitative empirical study of 30 informants who were involved in the exposure. And as the authors point out, they have all been subjected to various types of persecution within their organizations and perceived from the negative side (Kenny, Fotaki & Vandekerckhove, 2018).

Whistle-blowers might have had some positive impact on our societies, but overall their figure is seen as ambiguous and unsettling. The whistle-blower figure disturbs those witnessing it, raising emotional reactions often polarized in casting whistle-blowers, for example in the media, as either as saints or rats (Contu, 2014).

Obviously, a number of publications are devoted to the moral and ethical problems of activity of the corruption whistler-blowers (Bouville, 2008; Alford, 2007). After all, as in Ukrainian society as in the world, this kind of activity is ambiguous. Issues of motivation of the whistler-blowers are also relevant and investigated in the works of (Butler, Serra, Spagnolo, 2019; Ariely, Bracha, & Meier, 2009; Carson, Verdu, & Wokutch, 2008; Nurhidayat & Kusumasari, 2019; Park & Lewis, 2019).

Avakian & Roberts (2011) in their work argue that the study of the work of biblical prophets gives an idea of who is the whistle-blower and, in particular, about the institutional and personal dynamics that become apparent when people want to express concern about acts of illegal corporate behaviour (corruption offenses). The article also argues that studying about the role of prophets makes a profound contribution to understanding the experiences, roles, and attributes of those who become whistle-blowers (Avakian & Roberts, 2011).

We cannot ignore the scientific works devoted to the activities of police informants, which are related to the problems of the whistle-blowers of corruption. Crous, (2009) notes that over the last decade, the development of police intelligence has grown to such an extent that the term “police informant” has become obsolete as the practice of police intelligence includes the modernization and further training of traditional police relations with the informant. In the context of the modernization of the relationship between a police officer and an informant, the term “informant” has been replaced by such terms as “covert human intelligence source” (CHIS), “human source” (HS) or “human intelligence source”. There is no common single definition in police or legal information for sources of human intelligence, as police agencies in the UK, Australia, New Zealand and the US define sources differently (Crous, 2009). Such transformations in the world practice lead to the fact that countries being developed, also new phenomena are emerging as the institute of corruption whistle-blowers is confirmed.

Therefore, as we see in Ukraine and in other countries, the problems of the activities of the whistle-blowers are given some attention. However, there are no studies that examine the attitudes of citizens to the institute of corruption whistle-blowers in Ukraine. With the exception of slight sociological surveys, which are usually conducted by public organizations dealing with anti-corruption issues, such as Transparency International Ukraine.

Results and discussion

357 people participated in the survey. However, some of them, namely 6, provided incomplete answers, so their results were not taken into account in the analysis and interpretation.

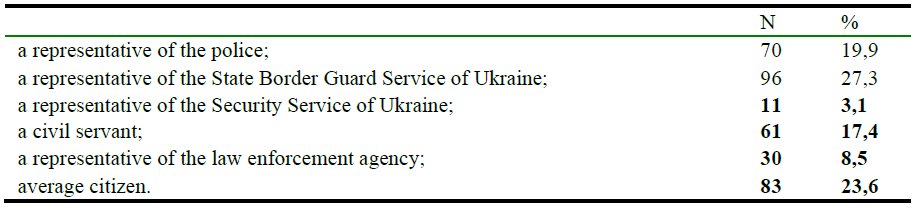

Table 1. Occupation.

By occupation, the respondents were divided as follows: 70 (19,9%) representative of the police; 96 (27,3%) representatives of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine; 11 (3,1%) representative of the Security Service of Ukraine; 61 (17,4%) were civil servants; 30 (8,5%) representative of the law enforcement agencies; 83 (23,6%) average citizens. Thus, four groups of respondents are representatives of the law enforcement agencies of Ukraine, one group is representatives of the civil service, and one group is representatives of the civilian population. The first 5 groups are both declarative entities and have a direct or indirect relationship with the anti-corruption system (Table 1).

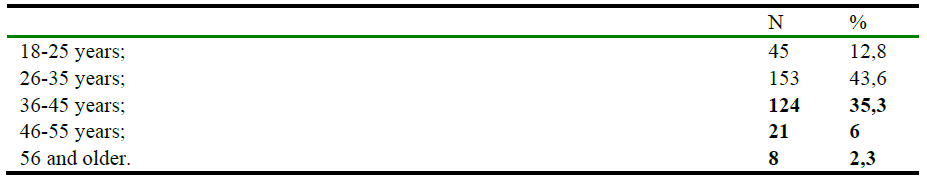

Table 2. Age.

By age, respondents were as follows: 198 (56,4%), the vast majority were between the ages of 18 and 35; 124 (35,3%) from 36 to 45 years; 21 (6%) aged 46-55 years, and the other 8 (2,3%) over 56 years. The survey covered the main socio-demographic groups (Table 2).

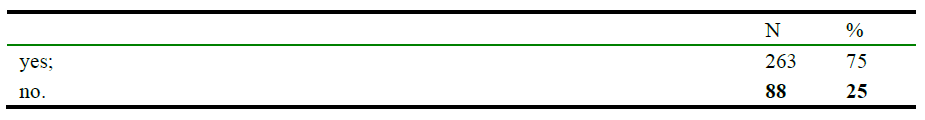

Table 3. Do you know about the existence of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers in Ukraine?.

When asked whether you know about the existence of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers in Ukraine, the respondents provided the following answers. 263 (75%) responded positively, 88 (25%) responded negatively (Table 3). Response groups were distributed as follows: 46 of the 70 police officers interviewed were aware of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers. From the 96 representatives of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine, 76 respondents know about the existence of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers in Ukraine, which is 79,2%. Representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine in the vast majority of 10 from 11 (90,9%) are aware of the existence of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers. 61 civil servants participated in the survey, 55 (90,2%) of whom reported that they knew about the Institute of corruption whistle-blowers. Among the representatives of law enforcement agencies 22 (73,3%) knew about the Institute of corruption whistle-blowers, and 8 did not know. 83 average citizens took part in survey, 27 (32,5%) of them said that they did not know about the existence of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers. This result is the highest among all the groups that participated in the survey.

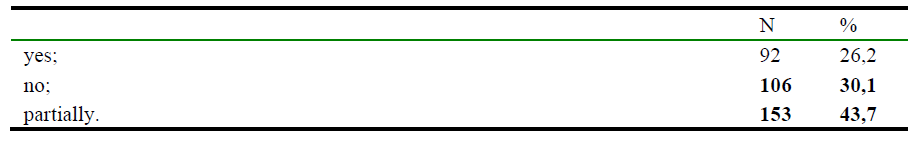

Table 4. Can the institute of corruption whistle-blowers reduce the level of corruption?.

We received the following answers to the question whether the institute of corruption whistle-blowers reduces the level of corruption in Ukraine: 17 (24,3%) of the police officers stated that this was possible, 18 (25,7%) denied such influence, and 35 (50%) of those polled believe it was partially possible. Border guards have a similar opinion, 24 (25,4%) of those polled agreed with this, 22 (23,1%) of those polled have the opposite opinion, and 49 (51,6%) of border guards believe that it can partially reduce corruption. Representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine are less optimistic only 2 (19,2%) of the respondents believe that it is possible, 4 (36,4%) of the respondents believe that it is not possible, 5 (45,4%) answered that it may reduce partially. Interviewed civil servants reported the following: 19 (31,1%) consider that it possible; 22 (36,1%) deny this possibility, and 20 (32,8%) believe that it may partially affect the level of corruption. Representatives of law enforcement agencies are less optimistic: 8 (26,7%) of those polled believe that it is possible, but those who thought that it was impossible were 11 (36,6%), and those who believe that whistle-blowers will be able to reduce the level of corruption partially were 11 (36.6%). Average citizens were the most optimistic: 30 (36,1%) of those polled believe that whistle-blowers can reduce the level of corruption; 21 (25,3%) do not think so, and 32 (38,6%) believe it is possible partially.

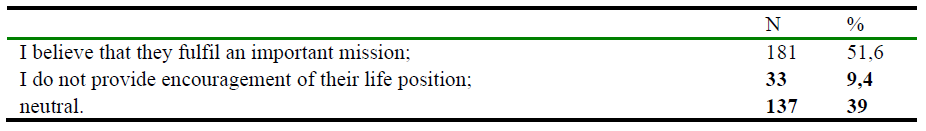

Table 5. Attitude to the institute of corruption whistle-blowers.

Speaking about the attitude of the interviewees to the institute of corruption whistle-blowers we have obtained the following results: 51,6% of those surveyed believe that whistle-blowers perform an important mission, 9,4% do not provide encouragement of their life position and 39% have neutral attitude accordingly (Table 5).

Speaking about the respondents’ attitude to the activity of whistle-blowers, results are the following: 35 (50%) of the police officers believe that whistle-blowers fulfil an important mission, 3 (4,3%) do not provide encouragement of their life position, 32 (45,7%) treat the perpetrators neutrally. Representatives of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine responded as follows: 57 (59,4%) provide encouragement of the activity of the whistle-blowers, 6 (6,2%) don’t provide encouragement and 33 (34,4%) have neutral attitude to the activities of the whistle-blowers. Representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine provided the following answers: 7 (63,6%) approve the activity of the institute of corruption whistle-blowers, 1 (9,1%) do not approve their activity, 3 (27,3%) have neutral attitude. Civil servants are somewhat less approving the institute of corruption whistle-blowers, only 28 (45,9%), while 9 (14,7%) do not approve their activities, and 24 (39,3%) respectively perceive their activities neutrally.

Representatives of the law enforcement agencies are most neutral to the activities of the whistle-blowers, 17 (56,7%) of the respondents, 12 (40%) consider their work an important mission, and 1 (3,3%) do not approve their vital position. The analysis of the survey results of average citizens did not differ significantly from other groups. Thus, 42 (50,6%) of the respondents positively perceive the activities of the whistle-blowers, 13 (15,7%) do not approve their life position, and 28 (33,7%) are neutral.

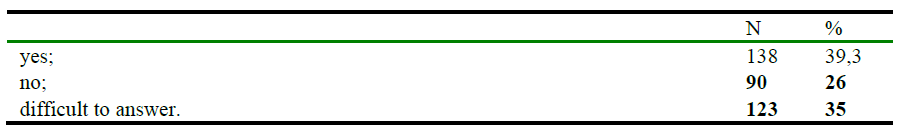

Table 6. Readiness to be the corruption whistle-blower.

The next question that is of major importance to us was the willingness of respondents to be engaged in corruption expose. Generally 39,3% were ready, 26% said it was not their business, and 35% chose answer (difficult to answer) (Table 6).

Response groups were divided into groups as follows: 36 (51,4%) police representatives are ready to be whistle-blowers, but 13 (18,6%) are not ready for such a mission, for 21 (30%) respondents the choice was difficult. 44 (45,8%) representatives of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine answered affirmatively, 17 (17,7%) are not ready to be whistle-blowers and 35 (36,4%) have doubts in the choice. Representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine were skeptical of the proposal to be whistle-blowers, only 2 (18,2%) did not accept it also 2 (18,2%) and 7 (63,6%) of the respondents hesitated with the choice. There were 22 (36,2%) wishing to be whistle-blowers among civil servants, almost 20 (32,8%) did not want to be whistle-blowers, and for 19 (31,1%) of the respondents it was difficult to answer. Representatives of the law enforcement agencies provided the following answers: 9 (30%) of respondents were ready to be whistle-blowers, 8 (26,7%) were not ready, 13 (43,3%) were also unable to make a clear choice. The average citizen shows almost the same results with the previous 25 (30,1%) were ready to participate in the exposure, 30 (36,1%) were not ready and 28 (33,7%) hesitated in choose.

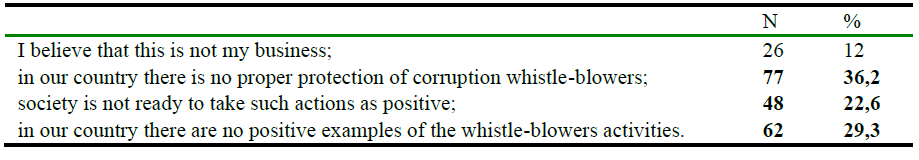

Table 7. Substantiate your negative answer.

The reasons that influence the respondents’ decision to choose the first answer in Table 6 (do not wish to be whistle-blowers) were as follows: four answers were chosen, with 12% of respondents considered it was not their business to be whistle-blowers; 36,2% believe that in our country there is a lack of adequate protection of whistle-blowers; 22,6% believe that society is not ready to take such actions as positive things (in part, these results are confirmed by the fact that 9,4% of respondents do not approve the activities of the whistle-blowers, and 39% consider their activities neutral, which may also indicate their disapproval selection Table 5); 29,3% of those who were interviewed said that there were no positive examples of the activities of whistle-blowers in our country (Table 7).

The analysis of the answers of the respondents who answered that they are not ready to be the whistle-blowers of corruption by groups gives the following results. Police representatives: 5 (14,7%) believe it is not their business to be whistle-blowers; 13 (38,2%) consider that in our country there is a lack of adequate protection of the whistle-blowers; 6 (18%) believe that society is not ready to take such actions as positive things; 10 (29,4%) police officers stated that there were no positive examples of whistle-blowers activity in our country. State Border Guard Service of Ukraine representatives have chosen the following options: 6 (11,5%) believe that it is not their business to be whistle-blowers; 19 (36,5%) consider that in our country there is a lack of adequate protection of the whistle-blowers; 12 (23,1%) believe that society is not ready to take such actions as positive things;

15 (28,2%) indicated that there are no positive examples of whistle-blowers activity in our country. Answers of representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine have some differences from the previous, 2 (22,2%) believe that it is not their business to be whistle-blowers; 3 (33,3%) consider that in our country there is a lack of adequate protection of the whistle-blowers; 2 (22,2%) believe that society is not ready to take such actions as positive things; 2 (22,2%) indicated that there are no positive examples of whistle-blowers activity in our country.

Answers of civil servants were thus divided: 3 (7,7%) believe that it is not their business to be whistle-blowers; 14 (35,9%) consider that in our country there is a lack of adequate protection of the whistle-blowers; 12 (23,8%) believe that society is not ready to take such actions as positive things; 10 (25,6%) stated that there are no positive examples of the whistle-blowers activity in our country. Respondents from among the representatives of the law enforcement agencies answered as follows: 3 (14,3%) said that it was not their business to be whistle-blowers; 4 (19%) consider that in our country there is a lack of adequate protection of the whistle-blowers; 5 (23,8%) believe that society is not ready to take such actions as positive things; 9 (42,8%) of those polled said that there are no positive examples of the whistle-blowers activity in our country.

The results of the analysis of the average citizens’ responses testified as follows: 6 (10,3%) do not think that it is their business be whistle-blowers; 17 (29,3%) consider that in our country there is a lack of adequate protection of whistle-blowers; 13 (22,4%) stated that society is not ready to take such actions in a positive way; 22 (37,9%) civil servants stated that in our country there are no positive examples of the be whistle-blowers activity.

The results are united by the fact that almost in every group the majority of respondents from 22,2% to 42,8% believe that in our country there are no positive examples of the whistle-blowers activities. This is really true, the resonant corruption cases in Ukraine are indicative of the persecution of the whistle-blowers. One example of persecution, which is a marker of the attitude of the political elite to the whistle-blowers, is Judge Larisa Holnik case. She was persecuted both by the head of the court in which she works and indirectly by the previous President of Ukraine, who without any explanations did not sign the decree appointing her a judge for a term of life (Completion of the case investigation on the claim of Poltava judge Holnik versus the President).

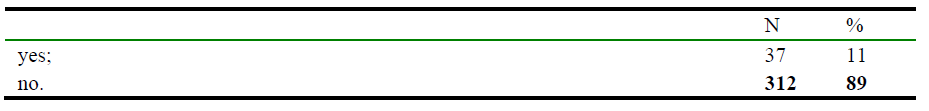

Table 8. Have you been involved in preventing corruption as a whistle-blower?.

The next question dealt directly with respondents’ involvement in corruption exposure. Generally, such answers were received, with only 11% of respondents reporting that they were involved in corruption exposure, and 89% were not involved in corruption exposure (Table 8). As we can see the percentage is very low. It is of particular interest to find out the level of involvement in corruption exposure by groups.

Thus, among the representatives of the police, the highest number of those who participated in the exposition of corruption as corruption whistle-blowers were 14 (20%) respondents. Only 12 (12,5%) were among the representatives of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine, while there were no such officers at all among the representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine. Civil servants and representatives of the law enforcement agencies have even lower rates of involvement in exposing corruption 5 (8,2%) and 2 (6,6%) respectively. And the worst result of participating in exposing corruption is shown by ordinary citizens. Only 4 (4,8%) of the 83 respondents found themselves involved in preventing corruption as a whistle-blower.

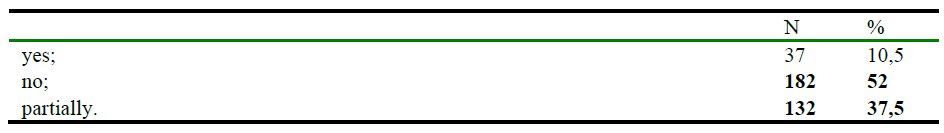

Table 9. Can the state protect the corruption whistle-blower?.

To the question whether the state can protect the corruption whistle-blower, the majority of those who were interviewed 52% answered negatively. 37,5% believe that partial protection is possible, and only 10,5% believe that such a possibility exists fully. The results were grouped as follows (Table 9). Only 8 (11,4%) of the police officers believe in the possible protection of whistle-blowers by the state, while 38 (54,3%) do not believe, and 24 (34,3%) believe that they can be partially protected. Border guards provided the following answers: 14 (14,6%) of those interviewed believe that the state is able to protect whistle-blowers, 45 (46,9%) disagree with this statement and 37 (38,5%) believe that protection is possible partly. Representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine are the least sceptical, 2 (18,2%) of those polled believe that the state is able to protect whistle-blowers, 4 (36,4%) believe that it is not able, and 5 (45,4%) believe that it is partially able. Civil servants and representatives of the law enforcement agencies are most doubtful about the state’s ability to protect whistle-blowers. Thus, only 5 (8,2%) civil servants and 1 (3,3%) representative of the law enforcement agencies believe that this is possible, while 35 (57,4%) and 13 (43,3%) do not think so. 21 (34,4%) and 16 (53,3%) respectively believe that such protection is possible partly. The average citizens are also pessimistic about the possibility of whistle-blowers protection by the state, 47 (56,6%) of the average citizens do not believe in the possibility of protection from the state and 29 (34,9%) believe that such protection may be partial, only 7 (8,4% of the respondents believe in the effectiveness of whistle-blowers protection by the state.

Table 10. Substantiate your negative answer.

Expert content surveys gave us the opportunity to identify two major problems why the state is unable to protect the corruption whistle-blowers from persecution and punishment in Ukraine. This allowed us to identify two main reasons. The first is that the “system” here means a corruptive “machine” that includes representative of authority (executive, judicial, legislative), as well as political elites who will do their best to deal with a whistle-blower and show the public that there is no sense in doing this (to be a corruption whistle-blower) because it will have negative results for them. There were 100 (32%) such answers of the number of answers of respondents who do not believe in the protection of whistle-blowers. The second reason is that the existing system of whistle-blowers protection is declarative in nature, according to 214 (68%) respondents (Table 10).

The groups of respondents were divided as follows. Among police representatives, 23 (37,1%) said that they should not be a whistle-blower, as the “system” would give short shrift to whistle-blowers, and 39 (62,9%) said that the legal and social protection of the whistle-blowers was declarative. Border guards provided somewhat different answers 20 (24,1%) chose the first answer and 62 (75,6%) the second. Representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine no longer trust the law, 8 (88,9%) believe that the legislation protection of the whistle-blowers is a simple declaration, and 1 (11,1%) say about the persecution of the whistle-blowers. The results of the survey of civil servants and representatives of the law enforcement agencies are as follows: the first answer was chosen by 12 (21,4%) and 12 (41,4%), respectively. The second answer was chosen by 44 (78,6%) and 17 (58,6%) respondents respectively. Responses to this question by average citizens differ from previous ones, 32 (42,1%) of respondents to pay attention to the whistle-blowers persecution, and 44 (57,9%) consider that the state is incapable of protecting the whistle-blowers because of the declarative nature of the legislation.

The analysis of the results gives us the opportunity to start a discussion. Ukrainian society is not convinced that the institute of corruption whistle-blowers can significantly affect the level of corruption in our country. Almost a half of the polled respondents (49,4%) perceive the whistle-blowers either negatively or neutrally, and only 39,3% are ready to be whistle-blowers. The index of almost 40% may seem quite high, however, the number of persons who participated in corruption expose as a whistle-blower was only 11%. There is a tendency that there is no proper mechanism of motivation to be a whistle-blower. Thus, there are two major legal models in international practice to encourage corruption whistle-blowers. The first and least effective, according to Dworkin, (2007) method is to protect whistle-blowers from retaliation. A later model provides incentives for whistle-blowers to supplement the provided protection. So the first model is built on a rational, but erroneous premise. The model assumes that most of the whistle-blowers are people of conscience and report about corruption without fear of reprisal. To this end, the law prohibits the prosecution of whistle-blowers, including through their discharge. However, the researchers indicate that these regulations are poorly effective. Even the introduction of criminal penalties is unlikely to be able to control retaliation against those who commit serious offenses (Dworkin, 2007).

The results of the study (Butler, Serra & Spagnolo, 2019) indicate that financial rewards significantly increase the probability that a person will participate in corruption exposure. The main motive for confidential cooperation is the material incentive motive – 47.6%. 21,3% of informants assisted the operations unit on patriotic reasons, compromising materials were a motive for cooperation for 19% of informants. 9,5% of informants provided assistance with motives for loyalty to Ukraine (usually foreigners or stateless persons). And only 2,4% cooperated with motives of envy (envy to other people’s success) (Khalymon, Polovnikov, & Volynets, 2020).

The national legislation of Ukraine provides for financial stimulation to corruption whistle-blowers. The Law of Ukraine “On Prevention of Corruption” provides for the possibility of paying pecuniary reward to the whistle-blowers. The right to reward is granted to a whistle-blower who has reported about corruption offense, monetary amount or damage to the State of which is five thousand times more than the minimum wage for the capable of working persons at the time of the crime commitment (in April 2020 this amount was 10135000 hryvnias, about 375,500 dollars). The amount of pecuniary reward is 10 percent of the monetary amount of the object of the corruption offense or the amount of damage caused to the state by the crime after the imposition of sentence by the court. The amount of pecuniary reward may not exceed three thousand minimum wages used at the time of the crime. This rule appeared in national law only in October 2019. That is why there are no examples of payment of pecuniary reward to whistle-blowers. However, we believe that imposing of this amount of damages in order to be able to pay pecuniary reward for the Ukrainian conditions is overstated. Losses from the vast majority (95%) of corruption crimes that occur in Ukraine are less than UAH 10 million.

Another problem is citizens’ trust in law enforcement agencies as representatives of the state. Comparing the obtained results, we also draw attention to the problems of trust to law enforcement officials, (Khalymon, Polovnikov, & Volynets, 2020) emphasize that the trust of the informant to the law enforcement representative is of great importance, the lack of such trust will not facilitate the psychological contact. We look at this problem more broadly; the trust should be first and foremost to the state, while 52% of the respondents do not believe that the state is able to protect whistle-blowers.

Citizens’ unwillingness to participate in corruption exposure is also explained by Miller (2011) noting that confidential whistle-blowing is filled with moral ambiguity and deception. Most of the interviewed respondents answered negatively or even were abused to law enforcement agencies. Whistle-blowers are abused because they are betraying others; however, detectives also try to deceive the whistle-blowers. Ironically, detectives exploit and betray their assistants, and that is in actual fact an immoral act (Miller, J. Mitchell, 2011).

(Butler, Serra & Spagnolo, 2019) based on an interview with 72 corruption whistle-blowers, have found that the vast majority of whistle-blowers experienced at least one form of workplace bullying after they reported about the offence. This was clearly influential, with 34 (47,2%) of the 72 respondents stayed at the previous job, while 38 (52,8%) said they had been forced to retire after they have become whistle-blowers.

The process of corruption offenses exposure involves a feature that cannot be fully discovered, accounted for and taken into account within the moral and ethical principles of society. This explains the limitations faced by empirical research aimed at understanding what drives people to become corruption whistle-blowers (Contu, 2014). According to the results of our study, only 39,3% of the respondents are ready to be whistle-blowers. Therefore, we can predict that a small proportion of individuals would agree to open interviews in order to find out the motives that led them to become whistle-blowers. So, at present, this does not allow for representative studies of empirical character.

As (Fitzgerald, 2015) affirms confidential whistle-blowers are an integral thread of the US law enforcement system, but their use is not without great risk and contradiction. However, the proper use of whistle-blowers is more beneficial because the information they provide is first-hand.

As we have noted in a previous publication, a person reporting about corruption automatically comes to fight with this negative phenomenon. And such a person must be sure of the end result of such a struggle. Absence of significant positive examples of the whistle-blowers activities in the vast majority of cases is due to the lack of desire of some individuals to act as whistle-blowers and the need to remain anonymous (Khalymon, Puzyrov & Prytula, 2019). Thus an increase in the percentage of citizens who would like to be whistle-blowers is due to popularization of positive examples. But in the Ukrainian realities we can observe absolutely opposite situation (persecution, intimidation, assault and battery, etc.).

Conclusions

The conducted research is a kind of contribution to the scientific literature on the problems of implementing the institute of the corruption whistle-blowers in Ukraine. In this article, we have analysed the results of monitoring the attitude of Ukrainian citizens (representatives of the National Police, the Security Service of Ukraine, the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine, civil servants, law enforcement agencies, ordinary citizens). The obtained results gave us an opportunity to find out the following: citizens of Ukraine in the overwhelming majority of 75% are aware of the institute of the corruption whistle-blowers; the mentioned results confirm the hypothesis №1.

In the whole, Ukrainian society has a positive attitude to the corruption whistle-blowers, which is also confirmed by the results of our survey – (51,6%) of those who were interviewed believe that the whistle-blowers fulfil an important mission. However, we believe that the percentage of people who do not approve their life position and activities (9,4%), as well as those who are neutral (39%), is too large. This may indicate that the level of corruption tolerance in Ukraine remains high. The willingness of Ukrainians to participate in corruption exposure is lower (39,3%) than the number of people who approve the activities of the whistle-blowers. It also shows that not all conditions, including the social and legal protection of whistle-blowers, have been created in Ukraine. The results partially confirm the first part of hypothesis №2; more than a third of Ukrainians are ready to be whistle-blowers. However, the second part of the hypothesis indicates that there is a high risk of persecution, including from the state authorities, according to (89,4%) respondents. This is also due to the fact that the existing system of whistle-blowers protection is declarative (68%), as well as in Ukraine there are no positive examples of the whistle-blowers activity (29,3%).

Solving the third objective of the study, it was found that there are differences in the attitudes of different categories of citizens towards the whistle-blowers. The biggest support (63,3%) whistle-blowers received from representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine, border guards (59,4%), police officers (50%), ordinary citizens (50,6%). Civil servants are less approving the institute of corruption whistle-blowers and support (45,9%). The lowest rate (40%) was shown by the representatives of the law enforcement agencies. Average citizens and civil servants (14,7%) showed the highest percentage of distrust in the work of whistle-blowers (15,7%). Thus, hypothesis №3 has not been confirmed, because law enforcement officials treat to the institute of corruption whistle-blowers more positively than ordinary citizens and civil servants who are not members of the law enforcement system.

.PNG)